Writing a murder mystery in which it turns out that the people you most suspect are the people who deserve the most suspicion might be seen as edgy and counter-conventional. Maybe it is. Sadly, it’s also really boring. Sometimes, breaking rules allows you to see that the rules were arbitrary and limiting, giving access to new perspectives and possibilities. In the murder mystery, however, it turns out that if you break the rule of trying to keep the investigator and reader from immediately identifying the perpetrator, you kill the genre and are left with a tedious procession to an ending that nobody cares about when it finally arrives.

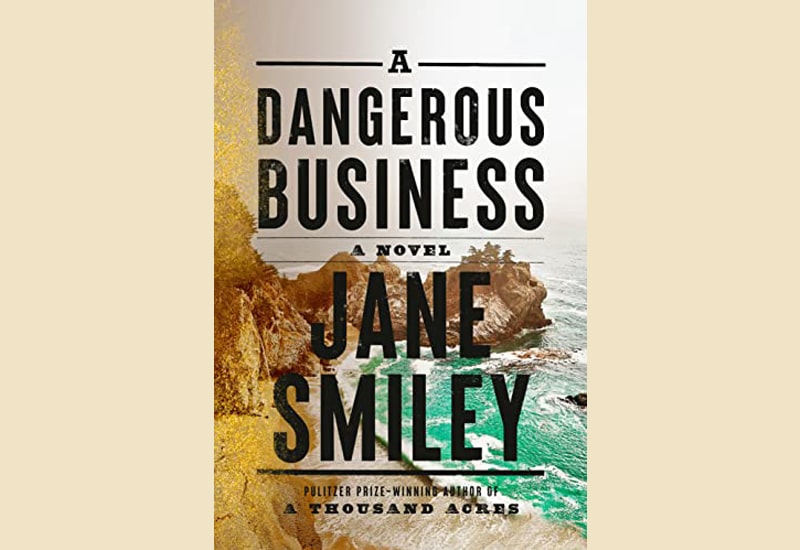

Jane Smiley decided to break this rule in A Dangerous Business.

Now, this error of judgement would be forgivable if the reader were made to forget about the ending; if the style were so dazzling, or the characters captivating and nuanced, or the plot constructed to shift the emotional charge beyond the investigation, then it wouldn’t matter that we know what’s going to happen. Unfortunately, the writing is flat and occasionally clunky: most of the language is historically non-specific, and then you realise that nobody in the book is capable of using any word for food other than ‘provisions’ for no apparent reason other than to remind you that it’s set in 1851. Eliza, the protagonist, undergoes no change at all from the novel’s start to its end, remaining decidedly chipper about having become a prostitute after the death of her abusive and idiotic husband; indeed, her chipperness is so unalterable that it is unaffected by the serial murders of other prostitutes, the sight of dead bodies, or even by the act of killing a man and disposing of the body. And nothing happens in the book at all aside from Eliza having sex with men and wondering whether they might be murderers, chatting about the men she thinks might be murderers with her friend and co-investigator Jean, and riding around on horses to places where dead bodies might – and usually do – turn up.

It didn’t need to be this way. The idea of prostitution as more liberating for women than marriage is an interesting one. It isn’t explored. Jean works in a lesbian brothel that tends to the needs of homosexual married women and heterosexual married women who just want the affection of another female. That could be interesting. It isn’t explored. Monterey, where the novel is set, only ceased to be Spanish in 1850, so one would assume that culture clashes and interesting hybrids would be rife. Not explored.

In trying to be interesting, Smiley has produced an impressively uninteresting book. There’s probably a lesson to be learned there.

Click here to change your cookie preferences