North is 140th on the corruption index along with Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan and Cameroon

A comprehensive study on corruption conducted in the northern part of Cyprus has revealed that it is extremely widespread, with 40 per cent of the business executives interviewed having resorted to bribery in the past year.

Seventy-two per cent of the 350 interviewed said bribery and corruption was ‘very common’.

Bribery was found to be most rampant among the ‘prime minister’ and ‘ministers’.

According to the study, which was based on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) methodology, the corruption perception score of the north for 2022, is 27 out of 100. On a scale of 0-100, zero indicates very high corruption and 100 indicates no corruption.

Transparency International, which publishes the corruption perception scores annually for 180 countries, does not cover the unrecognised northern part of Cyprus. Hence the need for this study by academics Sertaç Sonan an Ömer Gökçekuş, with the sponsorship of German Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) foundation, to measure the perception of corruption and to determine where it stands compared to the rest of the world.

The score of 27 is far below the average score of 43 in 180 countries and places the north in the 140th position on the index along with Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan and Cameroon. The corruption perception score of Turkey is 36, placing it in 101st position, while the corruption perception score of the Republic of Cyprus is 52, placing it at 51.

“This score is definitely worrying,” says Sonan, one of the academics, who conducted the study. The countries below us are the failed states most of which are going through civil wars.”

The study done for the sixth consecutive year demonstrates that corruption is on the rise. When the first study was conducted in 2017, the score for the north was 41.

As part of the study, a survey was given to 350 business executives, who are in senior managerial positions of companies. A separate survey was given to a group of retired high-level civil servants, who well know how the public sector mechanism works.

99 per cent say there is bribery and corruption

According to the findings, a staggering 99 per cent of the business executives, who participated in the study, say that there is bribery and corruption with 72 per cent believing they are ‘very common,’ while 54 per cent believe that corruption has worsened compared to the previous year. Ninety-four per cent of them said corruption is an obstacle to doing business.

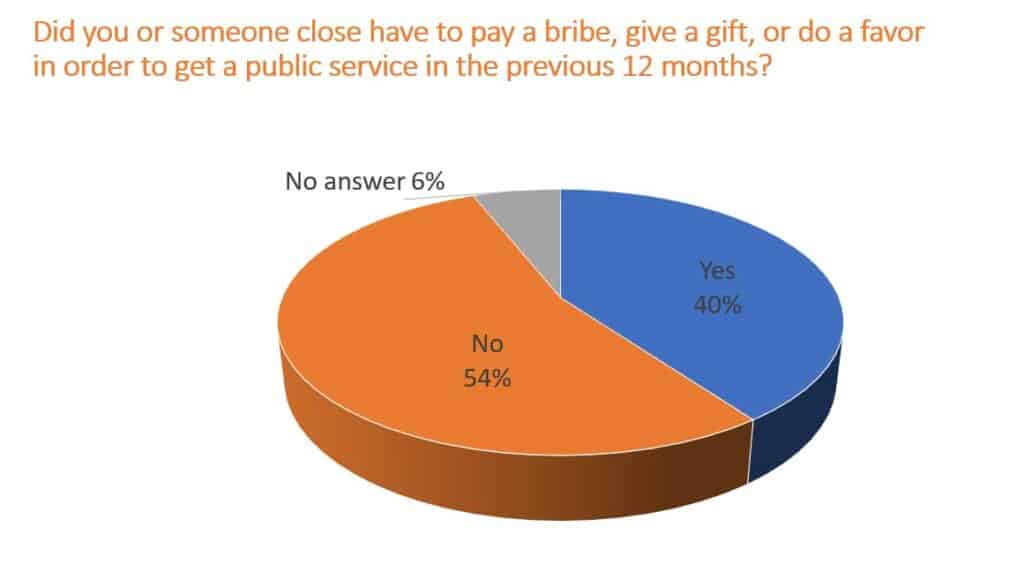

Forty per cent of the business executives admitted to giving bribes, gifts or doing a favour to a civil servant in the last year to expedite or finalise work, or to get favourable treatment.

Sonan believes the real number is well above 40 per cent as it is difficult for anyone to say

‘I gave bribes.’

According to the business executives, bribery or ‘undocumented extra payment’ is most common in public tenders, issuing permissions and licences, giving incentives and allocating and leasing public land and buildings. It is least common in obtaining favourable judicial decisions.

Those surveyed mostly held politicians responsible for corruption. According to 84 per cent, corruption is ‘very common’ among ‘prime minister’ and ‘ministers.’ These are followed by members of the Turkish Cypriot assembly (76 per cent) and high-level civil servants (69 per cent). While 33 per cent said corruption is ‘very common’ among lower-level civil servants, 22 per cent said corruption among prosecutors and 20 per cent said corruption among judges are ‘very common.’

The study shows that the participants’ trust in institutional mechanisms that are expected to prevent corruption is quite low. Eighty per cent said the ‘government’ is ‘not successful at all’ in fighting corruption. Seventy-two per cent said officials involved in corruption are not prosecuted. According to participants, the most effective institution in the fight against corruption are courts, but only by 16 per cent.

Political corruption

The survey also gave indications about political corruption. Seventy-five per cent of those surveyed said that it is common to buy votes or offer special favours during election periods. Thirty-four per cent said voters are frequently threatened with punishment unless they vote in a certain way.

Asked about the reasons why corruption is so widespread, Sonan mentions some shortcomings in the institutional infrastructure such as the lack of legislation, lack of qualified personnel, and most importantly, the highly politicised nature of appointments to higher levels of bureaucracy.

However, Sonan explains the grave increase in corruption especially after 2020 with a number of large scandals at the top of the Turkish Cypriot administration that have gone unpunished and even, in some cases, rewarded.

Some of these are the intervention against Mustafa Akıncı in the elections for the Turkish Cypriot leader in 2020; the AdaPass scandal – in which unvaccinated persons were issued fake safe passes for Covid 19 by the ‘health ministry’ in 2021 – the orchestrated collapse of successive governments in 2022, the murder of mafia boss Falyali in 2022 and his funeral attended by senior government officials, and the ongoing fuel procurements without tenders at the electricity authority.

“Accountability starts at the top,” says Sonan. “There is impunity here. All these scandals are taking place at the top and nothing is happening.”

The most striking of these scandals was probably the infamous ‘jet scandal’ in 2020. Ünal Üstel, who was the then ‘minister’ for tourism, gave special permission for a group of nine Turkish businessmen and three Russian escorts to fly into Ercan in a private jet and bypass the strict Covid 19 testing and quarantine rules. Soon after being dismissed from his position by the then ‘prime minister’ Ersin Tatar, Üstel returned to the top of the administration as ‘prime minister’ in May 2022. It has been widely speculated that Ankara is behind this appointment.

Sonan explains that this, coupled with the deep economic crisis that the Turkish Cypriot community has been going through in the past couple of years, makes people more inclined to resort to corruption. This explains worsening levels especially among lower-level civil servants.

“Hollowing out institutions though political appointments, rendering democracy and elections so meaningless through all these political interventions, moving away from meritocracy affects the society from the very top to the very bottom,” says Sonan. “Some say you have to hit rock bottom before rising again. I don’t believe in this analogy. For us, there is no rock bottom. We are in free fall and are constantly hitting more and more bottoms.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences