Over the last 70 years, Cyprus’ birth rate has plummeted. Alix Norman asks those who grew up in the 1950s what it was like to be surrounded by crowds of children

Monday, April 10 is Siblings Day. In Niger, it should be a riot – the average mother has 6.8 children. In Somalia, it’s six exactly. And in both the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mali, there are 5.8 kids per woman of child-bearing age. But in little old Cyprus, our fertility rate stands at a measly just 1.3 – the 14th lowest in the world and still falling, according to the latest data.

Do the maths, and you’ll discover that’s roughly four children for every three mothers. As more women in Cyprus choose to have just one child, and many decide to have none at all, our fertility rate has dropped into negative figures. The old definition of a nuclear family – two parents, two kids – no longer holds true in this country. Babies born these days are less likely than ever to have a sibling. But it wasn’t always so…

In 1950, the national fertility rate stood at 3.829, meaning that each woman of child-bearing age was producing almost four children. 50 years on, at the turn of the millennium, the figure had halved to 1.7. And, since 2020, the island has seen a drop in fertility rate of 0.6 year on year.

So, not only is the island’s population is rapidly ageing (by 2050, it’s predicted that half the island will be over the age of 65), but any children born in Cyprus are now less likely than ever to have a brother or sister.

There are exceptions, of course: families who pop out kids like there’s no tomorrow. But with birth control widely available, the cost of living at an all-time high, and the planet in crisis, many local women are making a conscious decision to have fewer children.

“Early on in life, I decided the best thing I could do for myself and the planet was refrain from giving birth,” says 36-year-old teacher Naomi Andreou. “You can use energy-efficient lightbulbs, take public transport, or eat vegan as much as you want – nothing comes close to the reduction in CO2 emissions you produce by refraining from reproducing!

“Times have certainly changed,” she adds. “Both my mother and father were from large families; four children in each. I do think that was a blessing back then: my dad’s family lost everything in 1974, but banded together to get back on their feet, and my mum and her siblings were parentless from a young age – they relied on each other through thick and thin.

“But now, there are too many mouths to feed, too much wrong with our planet,” says Naomi, who is already well along in the process of adopting a child from India. “I just can’t bring more children into a world that’s already in crisis.”

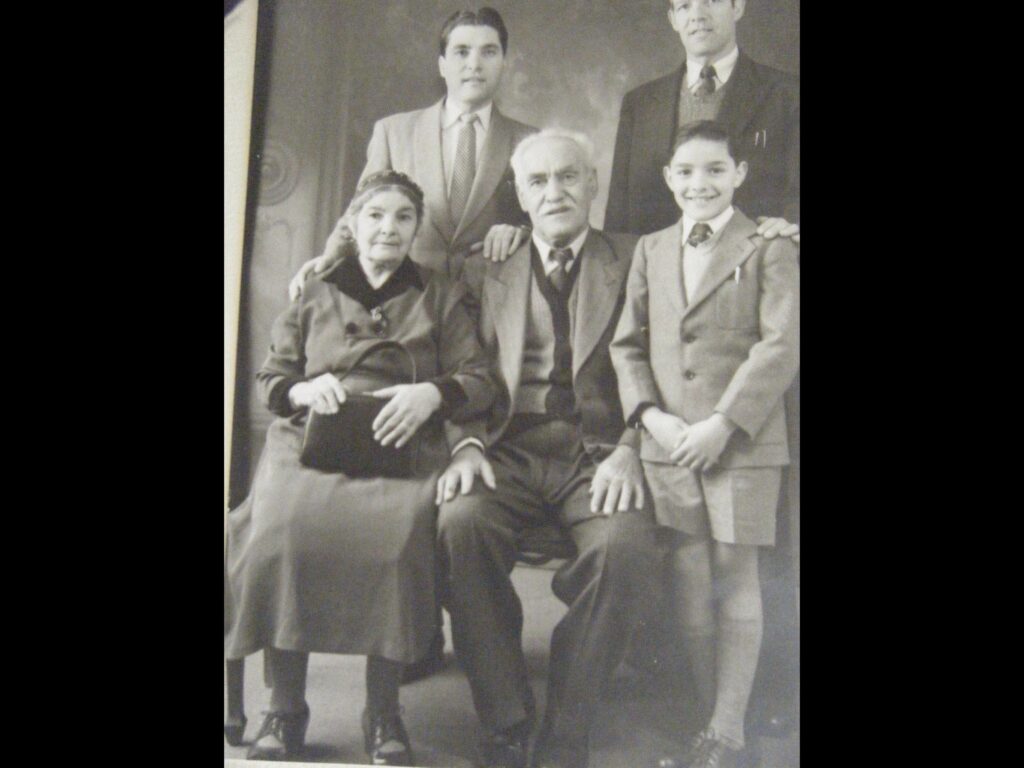

Deniz as a young boy (bottom right) with his father, uncle and grandparents on a visit to the UK. His grandmother gave birth to 11 children

In the past, of course, things were different. “We didn’t know about climate change back then,” says 73-year-old Skevi Louca, who was born and raised in the village of Genagra. “Everyone had large families, everyone had many brothers and sisters. There were kids everywhere!”

The eldest of eight, Skevi recalls family gatherings as riotous affairs. “Two of my aunts had four children each, another also had eight. My uncle wanted a boy so much he kept trying, but ended up with five girls! Plus there were hundreds of other children in the neighbourhood – we’d play tag all over the village, roam the area picking flowers and wild mushrooms.

“It wasn’t all play – we certainly had to help our parents a lot more than kids do nowadays,” she adds. “My mother was the village baker and my dad owned a cafenion and herded goats; they both worked very hard. And we worked alongside them. It was just what you did back then.”

In less developed nations, multiple offspring are often the norm. Lack of family planning, high infant mortality rates and limited educational opportunities for women are just a few of the factors at play. The same was often true of the past: the Vassilyev family, who lived in Russia in the 18th century, purportedly had 69 children, including 16 pairs of twins, seven sets of triplets, and four sets of quadruplets! But this claim has since been refuted due to lack of data.

“It was definitely harder to keep records in the past,” says 77-year-old Deniz Houssein, whose family hails from Anglisides. “Greek Cypriot births and deaths were recorded by the church. But we Turkish Cypriots had no such system: my grandmother wrote the birthdates of her 11 children on the back of her wardrobe door in Arabic,” he explains. “When the family left everything behind in 1964, that information was lost.”

Born in 1949, Magda Joseph’s family farmed land in Filia, Morphou. “I was the second of five; I had two brothers and two sisters,” she reveals. “It was normal back then, everyone had five kids or more. Though I do recall one family in the village had 10 children – that was a bit unusual!

“We helped our parents all the time: we cooked and cleaned and did everything we were asked. But we also had lots of free time with our brothers and sisters and the other kids; it was really nice to have so many friends your age. On our street alone there were 25 children. We used to say ‘five children can eat from the same plate’! And ‘in Cyprus, only the rich have just two children’. That’s certainly not the case these days, is it? Now, if you’re rich, you can have more children, not less!

“Women have full-time jobs and more responsibilities now,” she adds. “And I think that’s a very good thing. But I do miss the past. Each village was like one big family; there were a lot of children and a lot of love. Yes, life was hard in some ways. But, back then, it felt like we were all brothers and sisters; we all worked together. And people were so much happier.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences