In a bicommunalist and daughter of a political giant, AGNIESZKA RAKOCZY finds a woman with an international upbringing who wishes those on the island would learn to listen to each other and take a closer look at themselves

The first thing you notice about Kate Clerides is her positive energy. The 74-year-old citizen activist and former MP emanates open-minded, clear-headed, gentle optimism, a rare quality in a world that seems intent on drowning us in a daily deluge of bad news.

I meet her in the house she shares with her husband – business consultant and fellow peace activist Costas Shammas – and their four cats. The house is light and airy. The cats have their own custom-built outdoor ladder that serves as their personal stairway to the first floor studio where Costas works, a feature that immediately makes me more relaxed. People who build ladders to make cats happy are definitely my kind of people.

The past few months have been quite busy for Kate. Her new book recounting her more than 30 years in peace building efforts on the island has recently been published (Building Bridges in a Polarised World). Then, of course, there was February’s heated exchange between her and former president Nicos Anstasiades during the presidential election.

However, let’s start from the beginning. What I’m bursting to know is whether Kate’s father, former President Glafkos Clerides, actually wrote a letter to his future father-in-law Abraham Erulkar, an eminent Jewish doctor in Bombay, along the lines related by Niyazi Kizilyurek in his biography Glafkos Clerides: The Path of a Country.

According to the book, the letter read: “I am Glafcos Clerides. To you I am an unknown quantity of unknown quality but I am going to marry your daughter for the following reasons: (a) my in-laws will be 6,000 miles away, (b) she doesn’t know my language so I can say whatever I want, and (c) I love her.”

Kate laughs and nods her head affirmatively: “Well, my father always told this story, so yes, I am sure it is true.”

As a young woman with her parents at the airport

The year was 1946, she says, and her parents had met a year earlier in London, where her mother Lilla was working at the BBC. Glafkos, who had served in the RAF during the war and been captured by Germans, was not long returned from a prisoner of war camp. It was his sister Chrysanthi who introduced him to Lilla. She too worked for the radio station. Seemingly, Lilla’s father, who was personal physician to Mahatma Gandhi, replied in a succinct telegram with one sentence: “Advice wait a year.” Which they did.

Kate’s great grandfather, also Abraham Erulkar, was the main pillar of Ahmedabad’s Jewish community and a founder of the city’s synagogue. He sent his son, Abraham Junior to study medicine in the UK. Abraham married a Scottish woman while there and the couple moved back to India where, as an ardent nationalist, he supported the Indian independence movement.

Did her mother know Ghandi? Did Kate hear lots of stories from her mother about her childhood in India? She admits she has no idea.

“She never mentioned meeting him, so actually I don’t think so,” she says.

What she does remember is her mother’s story about her parents and how, just after they got married, they returned to India. “Her grandmother, my great grandmother organised a tea party in their honour. Apparently all the important ladies of the community were there and they started saying: ‘what will we do with our girls if all our best boys marry foreigners’ to which the hostess replied: ‘we will pickle them’.”

On the other side of the equation stood Glafkos, the son of prominent Greek Cypriot lawyer and politician Ioannis Clerides, who, having served as mayor of Nicosia in the late 1940s, ran as the Akel-backed candidate in Cyprus’ first presidential election in 1959. He lost to Makarios. Notably, Glafkos supported the Archbishop and not his father.

“Both my parents had a British education,” says Kate. “My mother was sent to boarding school at the age of 11 and my father in 1936 at the age of 17 after he was kicked out of school in Nicosia for writing articles in favour of the use of Demotic Greek (the standard spoken Greek) rather than Katharevousa (the conservative literary Greek conceived in the 18th century).”

The British-Cypriot-Jewish-Indian mixture must have made for an unusual upbringing I suggest and Kate nods her head.

At the launch of her book

“It was cosmopolitan and it definitely influenced the way I was brought up. My parents always told me that nationality and religion were unimportant compared to what counted, and that the only important thing was your character.”

The young family lived in London for a few years but decided to move to Cyprus in 1951. Kate was two years old — Cyprus was still a British colony. She remembers how she and her mother would often walk through Nicosia’s Old Town to visit Glafkos in his law office, which was opposite the law courts in the Turkish Cypriot quarter of the capital. There were regular visits to Rustem’s bookshop, and to sample the best galaktoboureko in Nicosia at Bedevi’s confectionery. There was a well-known Turkish Cypriot judge whose pockets she remembers as being always full of candies…

“We had Turkish Cypriot friends, it was a nice atmosphere. But it all changed when the armed struggle for union with Greece began. Things became different… suddenly we had roadblocks, barbed wire, checkpoints, soldiers with rifles, curfews…”

Kate was already attending the English School where, after all the other Cypriot students were forced to leave, she ended up as the sole remaining Cypriot.

Wasn’t it a problem, I ask.

“I guess, yes, it must have been. But my father was involved with Eoka. He was helping the people who were being taken to court by the British so somehow they [Eoka people] closed their eyes to me being there,” she responds.

“And I probably wasn’t even 100 per cent aware of what was happening. When people would ask me ‘what are you’ I would say ‘I am international’ because that was the way I thought about myself at the time. But yes, I did feel I didn’t belong there. I was an outsider. I wasn’t the same as everybody else because they were all English and I wasn’t.” Things got better after Cyprus became independent.

Glafkos Clerides’ political career was also progressing. Makarios appointed him the first minister of justice, and very soon afterwards he was elected House president.

But then 1963 happened and while there were no direct changes in Kate’s life she was aware that something significant had occurred. Turkish Cypriot students and teachers stopped coming to school (“the end of my Turkish language classes”). Her father’s law office and the courts had to move, relocating south of the Green Line…

Then Kate herself went abroad to study sociology and political science in the UK and US, subsequently qualifying as a barrister in London. In the early 70s, she was back on the island. The 1974 coup found her in Nicosia getting ready for a trip to Austria to attend a workshop organised by the American academic Leonard Doob, an expert on the kind of rapprochement procedures that could be used in attempts of solving the then political situation in Cyprus.

That would have been the first of the many bicommunal projects that Kate has since attended in the course of her career but alas it never took place. Participants were supposed to fly to Vienna on July 15, the day of the coup when Kate found herself along with her parents locked in the family house.

“We were all at home not sure what would happen. My dad was associated with Makarios and kind of under arrest. There was a military unit outside, not far from our front door, but there was no official arrest per se. Two or three policemen who were close to my father also insisted on staying with us, inside. That’s how we got through the week. Then the invasion took place and eventually they came to my father and told him that since Makarios was not in Cyprus he had to step in, and he did. Somebody had to run the country. I was seconded to the Red Cross and my mother went to the hospital to help there. In August we went to Geneva with my dad, where we lived through the talks there.

So yes, she was there through it all. In her words, “I lived through all of it but I didn’t see any fighting…”

Later Kate worked at the Commission for Refugees, a job that required her “to meet foreign journalists and explain the political situation to them.” She admits that at the time it basically amounted to “selling them the Greek Cypriot narrative” but hastily adds: “It doesn’t mean that I excuse the Turkish invasion in any way. It was later when she started asking questions and meeting Turkish Cypriots and heard their accounts that she realised “there were two parallel stories here.”

Her involvement in bicommunal activities didn’t start until the 1990s, whereas her political career had begun when she was elected a Nicosia municipal councillor in 1986. In 1991, she also became one of the first women MPs for Disy, the party her father founded in 1976.

It was around this time that she recalls being approached by Louise Diamond, a veteran of conflict zone negotiations, who raised the possibility of her joining some peace building workshops.

“My whole perception changed — this realisation that most of the time we are not listening to each other, that we are only telling our own stories, arguing but not listening… and that if we did listen we could find a way forward, it was priceless.”

At the outset, moving forward was clearly difficult. The workshops were monocommunal since it was virtually impossible to create conditions conducive to bringing Greek and Turkish Cypriots participants together in one place. Eventually some meetings were held at the Ledra Palace Hotel followed by a meeting in Oxford. A lot of accusations were traded by both sides in an atmosphere more suspicious than auspicious. But Kate and a core group from both sides perservered and went ahead. It was at one of these meetings that Kate was to meet the man who became her husband.

Indeed, she notes, some of the original group remain very active to this day. She frankly admits that commendable as this may seem, it also represents a matter of some concern. “The problem is not that people don’t want to get involved in bicommunal activities. The biggest problem we have is that somehow our numbers are not really growing.”

She admits however that after more than 30 years of being active in the bicommunal movement she doesn’t see how it can ever become more mainstream.

“The outreach is limited. And what seems worst of all is that we continue to preach to the converted.

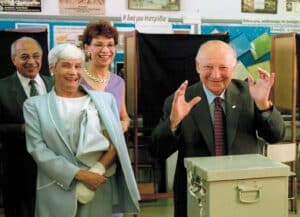

Voting with her parents

“The overriding narrative is that we are the victims and should not be giving anything away… that Turkey represents a big danger to us and so we musn’t give in … that we mustn’t sign an agreement since it would only serve to give Turkey even more influence in Cyprus … Unfortunately, because people are wrapped up in their own daily lives, they don’t have time to think about these things. They don’t question this narrative since they are just trying to make a living.”

She believes, insists, that the change has to come from the top down yet feels that it is unlikely to happen.

“Look at Anastasiades. He got elected on the basis that he was serious about solving the Cyprus problem. He started out on a good basis with [Turkish Cypriot leader Mustafa] Akinci, but somewhere along the line he lost his way. He left Crans Montana without signing a deal and he got away with it. Why?

“Because people wanted to believe in what he told them. People bought the Anastasiades version of what happened in Crans Montana because it was comfortable for them. The same way they bought the Papadopoulos version of what the Annan Plan was.”

Again she shakes her head, telling me that she finds herself more often than ever asking the question do people really want a solution in Cyprus, sadly, concluding that they don’t.

“They say they do but when it comes to the reality of the solution they don’t want it. They are comfortable in their present situation. I don’t see any real desire in our community for power sharing… so the truth is we are going nowhere. And the other thing is that nobody really cares about what will happen to the Turkish Cypriot community.”

Did these bottled up feelings and her sense of disappointment contribute to her decision just before the second round of the presidential elections in February to publicly air and share her opinion of Anastasiades, I wonder. Calling him “the biggest disappointment of her life”, Kate accused the former president of having betrayed the principles and values her father represented as well as having tarnished the party that raised him with what she termed the corruption of his government.

“I felt like I was in the Andersen fairy tale about the naked king,” she admits. “What I said was something everybody knew and talked about but not publicly. The only person who has said the same things out loudly is Makarios Droushiotis and yes, his books are selling very well but that is the end of the subject because otherwise nobody is paying any attention. The funny thing is that after I wrote it so many people swore at me but nobody said I was wrong. So I figured I must have been right. And that society needs somebody who will call a spade a spade. We need to look at ourselves more closely.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences