In an intense expatriate Cypriot, THEO PANAYIDES finds a woman open to difficult things who only felt free after leaving the cultural desert of Limassol and a violent childhood behind

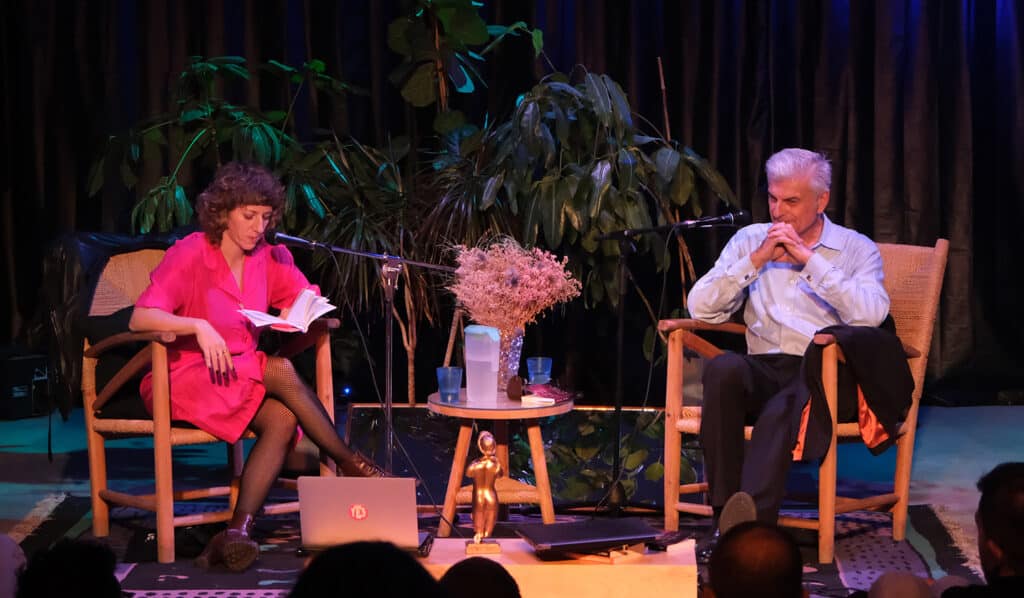

‘How we survived the 1990s’ was the name of the event (actually ‘Illicit desires and strategies of resistance, or, how we survived the 1990s’), Diana Georgiou in conversation with Stavros S Karayanni of the European University Cyprus. We talk two days later, Diana having come down from London – she’s an associate lecturer at Goldsmiths – in order to take part. ‘How we survived the 1990s’ with an emphasis on queer experience, part of a programme called Sessions that’s become a hub for queer artists, both from the diaspora and locally; she also has a book just published, Other Reflexes, part fiction part memoir, capturing “the difficulties of queer female experience in a deeply conservative and patriarchal society,” to quote the press release – though in fact her own 90s were a mixed bag, the worst of times and the best of times, the most turbulent but perhaps the most invigorating.

Her 80s were bad, no question. She was born in 1981 in Limassol, to a Cypriot father and a Polish mother; “I grew up around the wonderful area of Heroes’ Square [the red-light district], due to my father’s shady business. I was raised by many Filipinas at the time, in the 80s”. Mum was (and is) an artist, an excellent painter who’s done various jobs in her life but was probably happiest as a tour guide for local operators. Her dad, meanwhile, “wasn’t a very respectable man,” which is putting it politely. He was actually violent, beating Diana’s mother to the point where she filed charges, and finally went to jail for this and other crimes, at which point the family broke up. Diana was around nine years old, and the 90s were dawning.

“I was one happy bunny when they separated,” she recalls. “For me this was a massive relief, even though I could see that my mother was having a difficult time,” working multiple jobs just to survive. Diana herself – though she’d been spared the worst of the actual violence – felt a great liberation, not just what she calls an “independence from the father figure” but also a relief that she no longer had to dissemble when it came to her dad’s true nature, and her mother’s bruises. As she moved into the 90s – and her teenage years – she decided to be open and free, and put repression behind her once and for all. “It was very much an act of survival, an act of desperation. I think being in a situation where everything was behind closed doors, in the case of my parents’ relationship, as soon as we had that liberating moment I felt the need to expose everything. Because I didn’t want to be carrying all that darkness with me.”

The Other Reflexes book

She’s open in conversation: chatty, unabashed, lightly mischievous. She’s open professionally too, in her work as a writer and curator – open to what she calls “difficult things”, the kind that are not for the squeamish (she mentions curating performances “that entailed blood, that entailed piercing”); her most recent research article is on Rocío Boliver, a Mexican artist whose work “has redefined what we mean by pain in performance art”. Generally speaking, says Diana, “the interlinking between sexuality and violence is something that, let’s say, has become an angle by which I look at the world”. She has no red lines when it comes to art, unless it’s homophobic or racist; it seems absurd to talk of art being too raw or extreme, “in light of, y’know, exploding human beings from missiles” in the real world.

So how did she survive the 90s? By being open and indeed outspoken, having “heated conversations” and frequenting the three or four gay bars that were then a feature of Limassol nightlife. “I wasn’t repressed at all. I was quite an angry teenager, and I was hunting for any deviant sexualities possible,” she recalls with a laugh. Her own sexuality had been clear from an early age – what she then called ‘bisexual’ (she now identifies as queer), though only in a kind of theoretical sense: “I used that term in order to say I was very much able to have sex with men, I just didn’t feel I was able to do anything beyond that”. She’s not attracted to men, though the laws of attraction are complex in general: “My attraction is quite particular… I’ve only ever been attracted very strongly to maybe one or two women in my life. My current partner is someone with whom I felt, like, a psychic affinity that I could not explain.” Diana is not very visual, “I can’t look at someone and feel attracted to them” (she’s seduced by their voice, and the things that voice is saying) – which is odd since she’s visual in other ways, having worked for years as a photographer, studied Graphic Design, done a stint in TV production in Cyprus (a mixed experience) and thought about becoming a film director.

That TV job “broke me”, she recalls. It was the last straw, and the reason why she fled to London in 2007 – but in fact she’d always known that she would leave. Even as a teen, “I wanted out of the house, I wanted out of the city, I wanted out of the island”; she longed to write and flex her creative muscles, “in the cultural desert that was Limassol, this was very, very difficult”. Conventional life seemed like a bad joke. “Yes, the pressure was there for me to go get married, to go and be a ‘successful’ woman with three children and a very happy husband. Of course the pressure is there. But it was so incomprehensible, in light of every other woman that I saw around me who was suffering at the hands of men in very unhappy marriages, with so many kids they didn’t even plan for… My worldview was shattered so early on.” She chafed at attempts to placate her, and resisted women who advised her to just put up with it. “People around me could not give me answers”; instead she sought answers in books, pre-internet, sitting for hours in Kyriakou Bookshop reading all the books she didn’t have money to buy.

Money has always been tight; she’s been hustling all her life – and might not have coped, were it not for a close-knit community of queer friends. In Cyprus she worked in hotels, in a bingo hall, as a waitress, in a graphic design office. In London she’s worked stuffing sandwiches (her first job, from 3.30am till 7am; 300 sandwiches a night), in cafés, in a lesbian bar, selling churros at the local market, even in a shop selling bridal gowns; she still works three jobs now, as a curator and a photography technician at another university, in addition to Goldsmiths. The anger, too, has always been there – “I’m still angry” – though her younger version was more likely to act out. “I’ve spat in men’s faces,” she reports with a grin. “I’ve head-butted one guy.” That was in her teens, “my very angry teens… In my early 20s I spat at more men than you can imagine, I’ve said horrible things that would turn dead people in their graves. Not a great period of time”.

Maybe she felt unprotected? Like it was her against the world?

“Yeahhh…” she shrugs. “I’m not sure that I was looking for protection. It gets to the point where you become so tough that you just say ‘Bring it on’.”

Diana at sessions with Stavros Karayanni

Diana was on a mission – not just to fight but to explain, “trying to educate people about what it means to be non-heterosexual”. She doesn’t really do that anymore. “I no longer feel that it’s my job to do that. I no longer feel that, because we have same-sex partnerships. I no longer feel that, because we have some legislation on our side.” She recalls the time when the hate-speech law came into effect in Cyprus, about 10 years ago, as a defining moment. “When that law came out, it kind of shifted something in me psychologically… I don’t have to retaliate. I can take you to court”.

A lot has changed, but a lot has stayed the same. ‘Have you come to terms with it?’ I ask, perhaps naively – meaning the violence that surrounded her childhood (it wasn’t just her mum; “All the women around me seemed to be having horrific experiences at the hands of men”), and the years of banging her head against the wall of a heteronormative world. “When violence ends, maybe I’ll come to terms with it,” she replies with a touch of bitterness – and at first I think she means violence in general, but in fact she’s including herself, even now: “I don’t stop being a target just by virtue of being a lesbian”. Diana looks rather foreign in a Cypriot context, blue eyes and fair skin, which apparently makes a difference: “By the time I leave my house on my bicycle, from Tzamouda in Limassol to get to Anexartisias, I’ve already been catcalled three times. I can’t take a swim at the beach without having some dude lurking over me”. Admittedly she’s talking of Cyprus, not her main base in London – and admittedly she’s taking a broader definition of ‘violence’ to include harassment, which is another reflection of changing times.

The assaults haven’t ended, there’s a reason why her work still engages so strongly with violence – but her life has changed, all signs point to that. We talk about ways to unwind, and she has (or had) two. One was smoking, “a career in smoking,” as she puts it; “It was part of everything, y’know? Even the tactility of rolling a cigarette was seeing me through everyday life” – but she quit two years ago (booze was another crutch; she quit that long ago), and reports feeling far more serene as a result. The other thread in her life has been running, a meditative pause that allows her to be with herself. She tends to go running a lot more when she’s trying to work through something, says Diana – “and now is one of those times when I’m not running at all”. Make of that what you will.

Oddly, it was Covid that came to the rescue. Her 16 years in London have been tough, in many ways; she’s done a Masters and a PhD while also working all kinds of jobs and also falling into curating, starting to showcase artists and put on events (“exhibitions, screenings, you name it”) at often impromptu venues. It’s been exhausting, in fact her whole life has been exhausting – but then came Covid, “and I know people were having a horrendous time” but her own lockdown was something of a godsend. For the first time in her life, due to furlough, she had free time while still getting paid – hence the book, Other Reflexes (published by the London-based Book Works), but also a respite from the endless stressing and striving.

Sounds like she was able to catch her breath for the first time, right?

“Thank you! I’m glad you recognise it. Yes, it was the first fucking break! – I’m sorry to swear but… yeah, it’s been very hard. But also equally pleasurable in many ways, and equally hard. So, intensities have been at their peak almost consistently.”

Diana Georgiou is indeed quite intense – but also fun to talk to, partly because she’s so intense. Her openness and lively conversation spring from the same trait that informs her activism: a strong sense of self that’s also an intensely physical sense of self, a sense of her place in the world and a willingness to fight for it. I ask when she’s been the happiest – and she gives two answers, which are really two sides of the same coin.

The first has to do with the freedom of being in London and really coming into herself, not just able to love who she wanted (all her relationships in Cyprus had been closeted) but able to be who she wanted. “The idea that I’m walking down the street wearing anything I like, and no-one’s going to bat an eyelid. That was probably the most liberating my body has felt, ever. That, and swimming naked in the Limassol sea at 3am!” That’s her second answer, that wee-hours skinny dipping, a pleasure she takes whenever possible – and that too is a freedom but the opposite freedom, not the freedom that comes with finding oneself but with losing oneself. “Being able to feel that you’re so connected with the earth and the universe that you are pointless and meaningless! I think that dematerialisation of the ego is so important to me, where I’m just a vessel – and I think writing does that to me as well”. The freedom to be, and the freedom to let go. How to survive the 90s, and beyond.

Click here to change your cookie preferences