In a Turkish Cypriot public figure, THEO PANAYIDES meets a doleful doer who treated politics much like a business. While dismissing the chances of Cypriots living together again, he is more interested in motorbikes and guitars than the life of a politician, from which it is impossible to escape

As metaphors go, it’s quite an in-your-face one: Serdar Denktash sits in his office in north Nicosia, near the Ledra Palace checkpoint, absolutely dwarfed by a portrait of his father Rauf on the wall behind him. It’s not like it needed to be said, but there it is anyway: the burden of the most famous surname in Turkish Cypriot politics – and the burden of his father’s legacy, pressing down on 64-year-old Serdar ever since he plunged into public life in the late 1980s.

“People who used to know him closely, whatever I do or say they believe I’m not following in my father’s footsteps,” he admits. “Because they want me to act exactly like him. Which is impossible – because he was a different generation, he went through different problems. My generation is much more relaxed.” He shrugs, as if to say ‘What can I do?’: “So they’re not very fond of me, my father’s friends. Same with my brother’s friends”.

His brother was Raif, who died in a road accident in 1985. He was nine years older – but was also, more importantly, a political animal, the obvious choice to carry the torch. Serdar was a very different character. “During my teenage years, whenever I found myself in an atmosphere where they were talking politics, I used to run away. I really didn’t like it!” Instead he went into business, producing lingerie for export to Germany, and also did a stint as general manager of the Credit Bank of Cyprus – but then, the way he tells it, “when my brother passed away, in his last breath I promised him that I’d follow in his footsteps”. Thus he became – like Rajiv Gandhi in India, or Bashar al-Assad in Syria – a somewhat accidental politician, pressed into service by a brother’s premature death.

Actually, ‘pressed into service’ isn’t quite right – because it implies that Rauf pushed for a successor, which isn’t true. “No!” says Serdar with surprising vehemence when I ask the question. “Politics is not an easy game,” he explains. “It keeps you away from everything you need to do in your personal life. So no, he never wanted that.”

Does he himself regret having gone into it?

The laugh is hard to read, both sad and merry. The mood in the little office (previously the office of his son’s construction business) is mixed in general – the blinds drawn to shut out the sunlight, Serdar relaxed but also doleful, dressed in black with his father looming large behind him. There’s a rack of guitars in a corner, music being one of his lifelong hobbies.

An assistant offers me Turkish coffee, not ‘Cypriot’ as we’d say in the south – a small but noticeable difference, like when he talks about 1974 and mentions “the first… intervention”, pausing slightly as if to indicate that he’s choosing his words. (He missed that one, having been in summer school in the UK to improve his English.) Regret – so he claims – isn’t an issue, but what hangs in the air is perhaps fatigue, especially the fatigue of having worked so long at the same few problems. Serdar co-founded the Democratic Party in 1992, after two years at the National Unity Party (he fell out with its leader Dervis Eroglu), and stayed there for 28 years, 21 of those as its chairman. Is he now retired? “I’m retired from the parliament, but politics – you cannot retire from it.”

The burden of the name was always there, hanging over him. When he first went looking for political allies, his initial approach – through intermediaries – was to the moderate Mustafa Akinci; but Akinci spurned his advances, “because I am Denktash, I believe”, so he turned, almost inevitably, to the NUP, formed by his father in the 70s.

How did he view the other side?

“Growing up? I never felt, or thought from my father, that the Greeks are the enemies. But he used to say ‘We cannot trust them’.” He tells a story (I assume he’s told it before) from the intercommunal talks of 1968-72 between Glafcos Clerides and Denktash, the sessions taking place alternately at each man’s home. Serdar, aged around nine or 10, sat in on some of those sessions, typing rudimentary minutes with one finger. “I used to hear them talking – sometimes shouting, sometimes laughing. At the end of one of those meetings, Clerides said ‘Serdar, come’. So I sat on his knee. He said ‘Do you want me to take you to Makarios?’. I said ‘Okay’. Then my father said ‘But you have to drink the water that he washes his feet’ – so I jumped off Clerides’ knee and said ‘No, no, I’m not coming!’.” Years later, he ran into Clerides at some UN event and reminded him of the incident. “Well, that was the way your father brought you up,” mused Clerides. “Not to trust the Greek Cypriots.”

There’s a difference, of course, between individual Greek Cypriots – with whom he’s never had a problem – and their politicians, whom he does indeed mistrust. Could the Cyprus problem have been solved, at any time during his 32 years in politics? “Well, as long as the United States, UN, EU keeps saying to the Greek Cypriots that they’re the only legitimate government in Cyprus, and they represent the whole island, we will not be able to solve it. I mean, if I put myself in a Greek Cypriot politician’s shoes, I wouldn’t solve it either. Why should I share the power of what’s ‘mine’ with some other?” But surely they are the legitimate government, no? “The legitimate government, according to us, is the government of 1960,” he replies, “where the Turkish Cypriots were also represented.”

1960 didn’t work out, as we know. Then came “my father’s proposal, bicommunal bizonal federation, and we negotiated that for almost 50 years. Didn’t work out”. It’s too late, says Serdar matter-of-factly – adding to the somewhat doleful mood in the room – people on both sides have their own lives by now. “The island is big enough for both Turkish and Greek Cypriots to live side by side – but it’s not possible anymore to live mixed… So there are two sides, and we have to find ways and means of cooperating with each other. Political solution? Just leave that aside for now. It seems that we will not be able to do that. But cooperating? We should be able to do it. Trade-wise, economic issues, health issues, environmental issues. Why shouldn’t we be able to cooperate on those?”

But living together is not an option?

“It’s not. Not after 50 years.”

So then how is his position different to current leader Ersin Tatar’s?

Serdar just gapes at me, like I’ve asked a question in a foreign language. “I wouldn’t even consider to compare [the two],” he replies. “He is non-existent for me.”

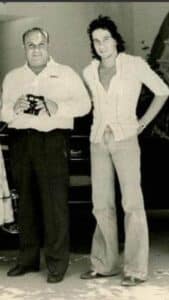

as a younger man with Denktash Sr

It’s an interesting nuance – because what he said does sound a lot like the two-state solution now being pushed by the Turkish side, but what Serdar has in mind is real independence, including (as far as possible) from Turkey itself. He’d like the north to be sovereign, not just an unofficial province of a bigger country. It’s true that he wants two entities, two nations: “I don’t believe in a Cypriot nation. Why? Not just because we have separate languages and religion, but in our history we never had a common aim, a common goal” – but he’s also entirely against any plan “to isolate ourselves from the other half of the island,” and in fact has been instrumental in bringing the two sides closer in practical ways: “If you are using the phones right now, it was me who gave the permission first. Opening all the crossings, it was me who fought for it for three years”. As finance ‘minister’ in 2016-19, he lowered duties to stimulate trade from the south. This wasn’t just politically driven, of course, it was also lucrative; indeed, one might say that Serdar Denktash – a businessman thrust into politics by personal circumstances – tends to treat politics like… well, a business.

Business is the art of saying ‘yes’. It’s important to secure a good deal, of course – but it’s also important to innovate, take some risks, be open to new ideas. Politics, on the other hand (especially as practised by his father’s generation), is often the art of saying ‘no’ – being cagey and stubborn, trying to wear the other side down. Serdar, temperamentally, has always felt closer to the former than the latter. One hallmark of his career is the number of portfolios he’s held in various governments – he’s been ‘minister’ of finance, the interior, tourism, foreign affairs, you name it – and he’s always made one thing clear to his team: “I will never accept an answer ‘No’. You will come to me [and say] ‘If we want to do this, this is the way to do it. Change the law, take this option, whatever’”.

In short, he’s a doer – a trait that extends to his hobbies, which tend to be active and adrenaline-fuelled. Music’s been a huge part of his life, playing bass and acoustic guitar in a folk band (they still play, though mostly by invitation these days). He also goes sailing on a 44-foot motor boat, and is also “a real hardcore Harley-Davidson” fan (he has three bikes, a Trike, a Sportster and a Fat Boy) who likes to hit the road whenever possible – in the Karpas, sometimes in Turkey, or “sometimes we cross to the Greek side and ride there”.

He’s also (speaking of dangerous hobbies) been married for 43 years, with three children and four grandchildren – though politics got in the way, yet again. “I neglected my children,” says Serdar, adding yet another doleful note to our meeting. “I wasn’t there. Not enough. Probably more than what I saw from my father, but still – not enough. And you can sense that. When you see your children’s friends with their families, the relation they have, and the relation I have…” He shakes his head, regret seeping in once again.

Maybe you’re just projecting, I suggest reassuringly.

“Maybe… I mean, I never complained about my father. And I’m hoping that they’re not going to complain about me.”

There’s a bittersweet mood in the little office, a middle-aged man looking back on a life that’s been full, productive, successful – yet also unplanned, unsolicited, enforced by the burden of his famous name, finally a bit exhausting. “Personally, I’ve changed a lot,” he muses ruefully. “I was a very happy man before the politics. I used to love travelling, enjoying myself. In later years, I lost that. I lost the love of travel, I lost the…” Serdar pauses, shrugs: “It’s not easy to explain, but… You get to know new places [when you travel], you meet new people. But in politics you concentrate on the problems, mostly. That kills your enthusiasm to do better.”

The Turkish Cypriots, too, seem a bit exhausted, even melancholy. “They’re not happy,” sighs Serdar when I ask about his people, and the general climate in the north. “They are not happy… We used to be more helpful to each other. We used to have more respect for each other. But nowadays that happiness is gone – although we have everything, money, cars, houses, whatever, but the respect towards each other has faded away… And that makes us unhappy”. He sees them when he plays with his band, still making noise, the community still standing strong – “We are here. And we’re not going to leave” – but increasingly anxious, unsure about the future, conscious of all the bright young people moving away.

‘What about the New Year?’ I ask, trying to end the meeting on a positive note. Maybe 2024 will be the one – but Serdar just smiles. “Nah, nothing will happen,” he says softly. “Nothing will happen. Not with this government, at least. And not with the government in the south. I don’t think they have the need to come together to solve anything, so…” He shrugs, letting the sentence trail off. It feels like we’re coming to the end – of our interview, and perhaps the Cyprus problem, and the old world of the patriarch gazing down from the wall behind him.

Click here to change your cookie preferences