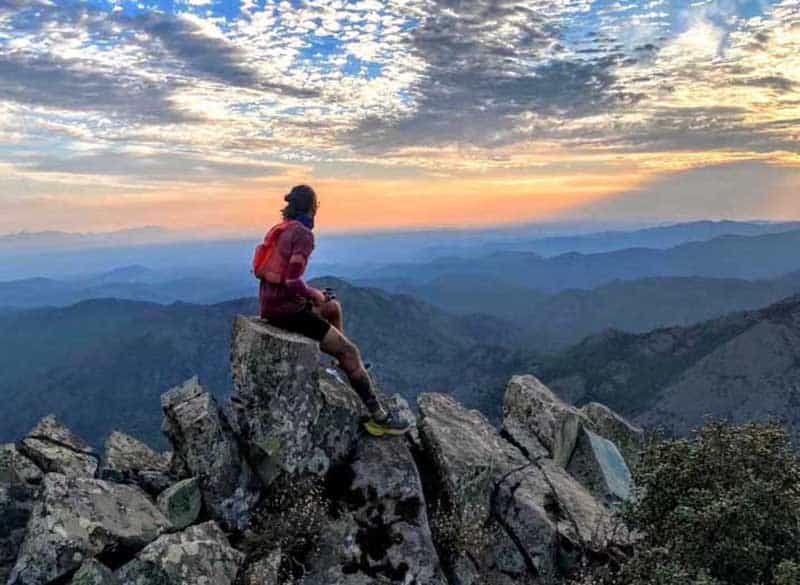

THEO PANAYIDES meets an ultra runner with a warrior’s tenacity in search of a hippy’s sense of freedom, a man who finds freedom when moving through nature

Some have reported hallucinations. “I’ve heard stories where people say they saw an animal playing a musical instrument,” reports Viktor Olov Leonidou in the Nicosia flat he shares with his partner Romina. “Or small creatures by the side of the trail.” 20 or 30 – sometimes even 40 – hours of running will do that to you; Viktor is a trail runner and specifically an ‘ultra runner’, meaning he runs in the mountains for hours on end.

He was in Wales last May, for instance, running the Ultra-Trail Snowdonia, a 168km race with an ‘elevation gain’ of over 10,000 metres. What that means is that – even though Wales doesn’t have high mountains per se – if you added up all the uphill stretches it’d be like having climbed from sea level to a height of 10,000 metres, which is five times the height of Troodos – and of course that’s only half the story since the uphills alternate with downhill stretches, which can be even trickier.

That race took him 33 hours and was, he admits, very difficult – though not for the obvious reasons. “I thought I was prepared but it turns out I wasn’t. Because in Wales in the mountains they have something we don’t have in Cyprus – the bogs.” He’d seen photos, but wasn’t expecting the soft marshy ground to be actually part of the route. Trudging in muddy water up to his knees, his socks and boots sodden for hours, was deflating and energy-sapping – but the key point is that he hadn’t expected it: “The psychological factor is the most important thing in ultra running, it’s bigger than fitness… Because you’re out there for a long time by yourself, in your own head. So you have to deal with a lot of thoughts”.

He’s never experienced hallucinations himself, says Viktor – but “I’ve had races where I got an obsession stuck in my head”. In August 2022 he ran the UTMB, the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc, the most prestigious trail-running ultramarathon in the world (he finished a very creditable 218th out of 1,789 runners) – and, as he dragged his unwilling body up the final uphill, he couldn’t shake the notion that that stretch of trail had been specifically designed by Kilian Jornet, a sporting legend and author of the book Run or Die. The idea had no basis in reality – yet he couldn’t stop thinking about it, his absurd resentment of the innocent Jornet distracting him from the task at hand.

It was his mind trying to get him to quit, explains Viktor – because “one of the basic things you have to confront is your mind, over these kinds of distances. Because your mind is going to tell you ‘Stop, it’s hurting. Enough. You’re tired. Stop’. And part of the experience is that you have to overcome your mind, and say ‘I’m stronger than you – and I’m going to continue’. Because the easy thing would be to say ‘You’re right, I’d better stop’.” There are organised pit stops on the trail every 20km or so; a runner can retire at any time. He finished 18th in Wales, out of 250 who started – but in fact only 90 of those actually made it to the finish line.

We sit in the living room with a view of the city, a sixth-floor apartment in a very old building. (“I usually take the stairs,” he admits, unsurprisingly, as we wait for the rickety lift to arrive). I peruse the bookshelves while he makes us coffee, noting the aforementioned Run or Die as well as Haruki Murakami’s What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, the Japanese author’s slim memoir where he draws connections between his twin passions of writing and long-distance running – both very solitary pursuits, if nothing else. I’m surprised to find books about birds (Romina, it turns out, works at BirdLife Cyprus) and even more surprised to find Neil Gaiman’s book on Norse mythology, in Swedish – but Viktor’s mum is Swedish, so he speaks the language. There are photos of him as a boy, looking shaggy and considerably blonder than he is now. These days his look is distinctive, dominated by tufts of black beard and “stretch” earrings (“You start with a small hole, then open it up bit by bit”), the kind worn by Amazonian tribes that sit below the ear like a new lobe.

It’s a bit of a conundrum, sitting opposite this 29-year-old man with the rather fierce appearance, soft-spoken style and unusual occupation (though the running isn’t work, at least not yet). What’s he actually like? “I’m an introvert,” he explains frankly, “who for many years wouldn’t talk, and avoided talking to people – or at least starting conversations”. He didn’t feel comfortable talking about himself, or sharing his opinions. “I feel like the running also helped me with that. To discover who I am a little more, open up to other people. I don’t care how people judge me because I feel comfortable now, and I know who I am… More or less,” he adds, as if to say it’s a work in progress.

Oddly enough, he only started running five years ago, and very much by accident. His mum heard about a 20km race in Akamas, and convinced him to come along just for fun. Neither had run before; both caught the bug. (Viktor’s mother is also into trail running – albeit not quite so heavily – and has run up to 135km, despite being in her 60s.) He was indeed a novice at the time, which is too bad (“If only I’d started running as a kid, I think things would be different now”), though he’d always been sporty, football at school then martial arts (Muay Thai) for a while in his teens. Those were his introvert years – and also the years when he became a hardcore football fan. “I was Apoel – in the stands, with the fans,” he explains a little vaguely, all too aware of the thin line between organised fandom and hooliganism.

It’s an interesting detail, albeit no longer relevant per se. “That’s a part of my life I’ve left behind,” affirms Viktor. “I don’t regret” – he pauses slightly – “what I experienced, but I saw some things that I don’t agree with”. There were fights, presumably, and violence, though he himself never took part in any ‘incidents’. He’s not a violent person, if anything “I think it’s the opposite”: the main reason why he switched to a plant-based diet in 2015 was precisely that he hated the thought of hurting another creature (he’s since discovered that it also helps with the running, especially in shortening his recovery time). What’s intriguing about his Apoel phase is the way it fits into a pattern, how it fed the need to belong – to a tribe, a shared passion – and how it fed the atavistic warrior mentality that’s important for so many young men, and now finds an outlet in ultra running.

What he said about having to ‘overcome your mind’ while out on the trail, for instance, is something all young men would’ve been quite familiar with in pre-modern days. A warrior going into battle, or a Viking setting out on uncharted waters, would surely have received a panicky message from inside his head saying ‘Stop, this is dangerous’, and required the mental strength – or just the tribal solidarity – to push it aside. Viktor is drawn to that whole mentality, hence the interest in Norse mythology (his main tattoo, on his back, is apparently Norse-related); the Vikings – he tells me – weren’t just marauders, they were explorers who lived close to Nature. That last bit is especially important: running in Nature, he says on his YouTube channel, “over rivers, along mountain peaks – to hear the birds, to hear the water… For me, it’s the closest you can get to freedom”.

It’s not quite that simple, of course – not just a case of abandoning oneself to the universe. The ultra-running community is very close-knit (echoes of his Apoel years), the top runners never looking down on the laggards – after all, points out Viktor, a pro might do Mont-Blanc in 20 hours but the last runner might finish in 44 hours; it takes extra strength to accomplish that – but running is also a case of a solo sport where you have to be in total control of your immediate environment. You can’t just ‘move’, you have to know what you’re doing. You have to eat something – mostly bars and energy gels – every hour or so, or the body goes haywire (that’s how hallucinations happen). You have to fight solitude, especially at night; he recalls one 160km race in Greece where he was solidly in fourth place almost throughout, separated both from the top three and the pack behind him: “I finished in 23 hours, and maybe for 20 of those hours I didn’t see another runner on the trail”. Once control is lost, the whole edifice collapses; that’s why the unexpected bogs in Wales were so damaging.

It’s a synthesis, like the task of the meditating yogi or the monk in the desert: arduous concentration in the service of a higher purpose, a warrior’s tenacity in search of a hippy’s sense of freedom. The rest of his life is more modest – and less accomplished, at least so far. “I’m still searching…” he admits a little bashfully – and recalls a film he saw as a child about Tarzan in the city, the king of the jungle in the urban jungle, looking around with the same wry bemusement that Viktor also feels sometimes.

He’s between day jobs, currently helping in his dad’s catering business; he was previously at a company making nut butters, but left a couple of months ago. His lifestyle is simple, ascetic; having kids – the usual definition of ‘settling down’ for a man who turns 30 in May – isn’t on the cards at the moment. He’d love to make running his profession, says Viktor – but of course finding sponsors is impossible in such a small market. The best he can do is product placement, like the fancy sports watch (a Suunto) which he was gifted, and often displays on social media.

It’s not just sponsors; the culture here is a struggle in general. Cypriots are notorious for littering (Viktor will stop in mid-race if he happens to drop the wrapper of a protein bar, turn around and pick it up off the trail), and so allergic to walking – never mind running – they’ll take the car to go down the street to the kiosk.

He tries to fight that, if only by example. “I think one of the best things about ultra running,” he muses, “is that you’re doing activism without even knowing it,” promoting Nature without any need for a soapbox. His biggest project to date (it took place last February; you can find a 37-minute movie on his YouTube channel) was called Lighthouse 2 Lighthouse – a three-day, 300km run across Cyprus, from Cape Greco to Akamas through the mountains. Viktor’s been everywhere on the island, though he still hasn’t tried the steep uphills of the Pentadaktylos range. He’ll cross the Green Line eventually, he says, just “not yet”; I suspect a slight reluctance still remains, from his Apoel days.

All that said, things are changing. The Cyprus Ultra Marathon is apparently coming this summer, including a 217km ultramarathon that’s being billed as “the world’s toughest hot trail race”. (Having a long-distance race in the extreme heat of a Cyprus summer does seem a bit mad.) Viktor isn’t involved with the event, though – as the island’s No. 1 ultra runner – he’ll presumably grace it with his presence. He has two races already booked this year – in Madeira and North Macedonia, both over 100km – and also hopes to run Mont-Blanc again, assuming he makes it through the lottery system.

Running feeds his soul, it uplifts him. It’s freedom, it’s Nature, it’s the sense of purpose of his football-fan days without any ugly violence. It’s pushing your body to the limit – and maybe seeing a fox playing electric guitar by the side of the road; “I’d like to keep doing it,” he admits, “till I die”. The joy of moving, and keeping on moving.

Click here to change your cookie preferences