In a Turkish Cypriot poet who gained notoriety through what became an 80s anthem AGNIESZKA RAKOCZY meets a woman who was always a rebel but has only reunited both sides of herself since the crossings opened

There is an old video on You Tube showing Nese Yasin and Marios Tokas at the Camden Cypriot Festival. The year was 1991, and it was one of the first encounters between the Turkish Cypriot poet and Greek Cypriot composer. Together they perform – in Greek and in Turkish – Yasin’s most famous poem My Country Has Been Split in Two to music Tokas composed. Yasin’s words, written 15 years earlier, when she was a 17-year-old student, flow from the stage: “They say every man must love his country – my father often says so too. My own country has been split in two – which part should I love.

“It took me three minutes to write this poem,” Yasin recalls. “It was published in a Turkish literary magazine by the Turkish poet Ataol Behramoğlu. It was my debut. Behramoglu brought a copy of the magazine to a festival in Bulgaria and gave it to the Greek Cypriot poet Elli Peonides. She got curious so she found somebody who spoke Turkish and had my poems translated. When Marios read my poem in Greek it took him three minutes to compose music. So all in all, it took six minutes – six minutes that change my life…”

Nese was born in 1959 to a Turkish Cypriot family that lived in the mixed village of Peristerona. Her maternal grandfather was the richest land owner in the village (“Peristerona was an interesting case because Turkish Cypriots had more land there than Greek Cypriots, while usually it was the other way round”).

She remembers the village fondly.

Nese can hardly remember a time when she wasn’t composing poems. Her father, Ozker Yasin, himself a well-known Turkish Cypriot poet, liked to read poetry aloud at home. “Poetry was just part of life… something organic, like a fate. I never decided to become a poet. I was just imitating my father. I started making poems when I was four…”

That first “magical” phase of Nese’s life came to an abrupt end when the family had to leave Persiterona after the events of Christmas, 1963. The sense of dread and fear, the memory of what so suddenly changed the course of their lives, remains indelible. “Our house was full of neighbours – men were upstairs with guns, women gathering downstairs… Armed Greek Cypriots were surrounding the house. My grandmother tried to open the door and somebody shot at her. There was nothing to eat. My father and grandfather were not there. They had just gone to Nicosia in my father’s new car and got stuck there.”

Nese’s mother was just about to give birth and had to get to a hospital. But how? It was decided that two Turkish Cypriot men would drive her and and her mother-in-law in her grandfather’s car. On the road, they were stopped by armed Greek Cypriots and the two men were arrested. “The militia called a Greek Cypriot neighbour of ours and she was allowed to take my mother to hospital in Nicosia. Luckily, the two Turkish Cypriot men survived but my grandfather’s car disappeared, never to be seen again. So did the layette for the newborn that had been so carefully packed into the car by the two women.”

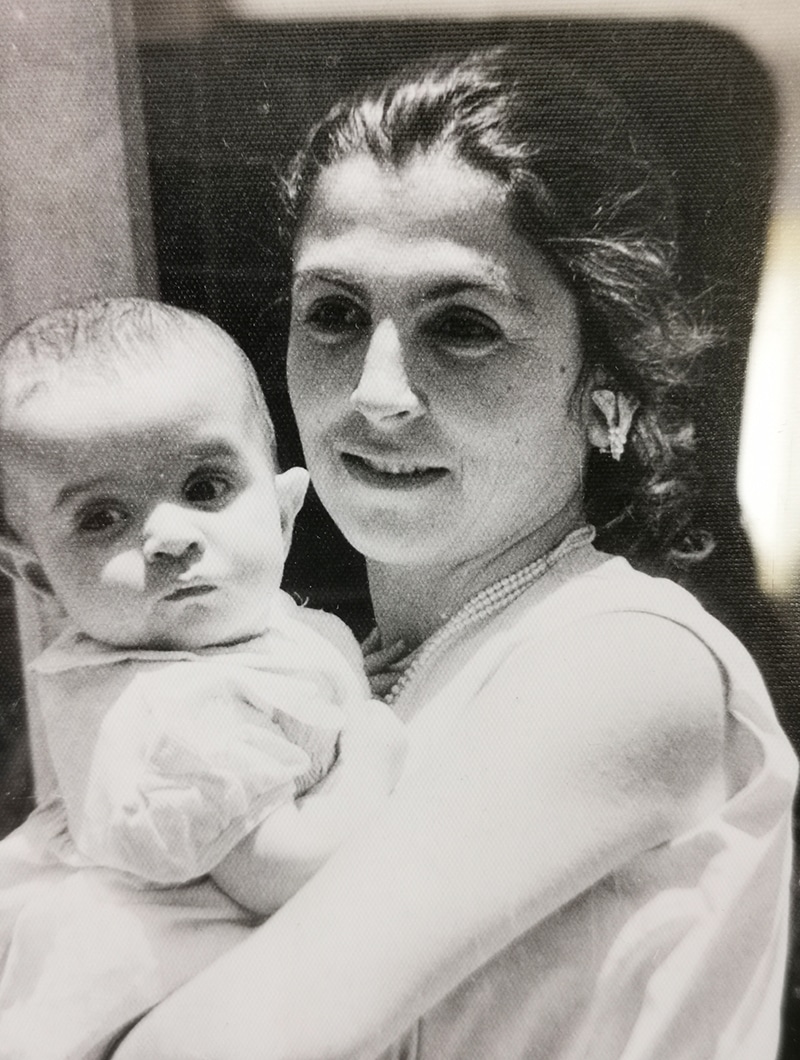

Guarded by a Greek Cypriot soldier with gun in hand, Nese’s mother gave birth to a healthy boy. The newborn was wrapped in his grandmother’s shawl, all they had to clothe him with. Nese’s mother returned from the hospital traumatised.

Nese as a baby with her mother

The family quickly evacuated from Peristerona to Nicosia, living together with the other Turkish Cypriots in the enclaved part of the old town. In 1967, when the situation had normalised a bit, they were told they could go back to the village. Nese’s grandfather did go back but only to take care of his orchard, the house had been looted. “I had a lot of dolls and I remember I couldn’t wait to get them back. But not a single doll was there…”

Years later, in the early 90s, her poem now, as she put it “famous”, she was in London when someone from Akel promised to arrange to get her a Cyprus passport so she could go there. “So I got a plane ticket and then he said there was no passport… Somebody else then advised me to go to the embassy and ask the ambassador for help. The ambassador knew of me and agreed to help. He said he would issue me a special visa that would await me on arrival.

“So I flew from Gatwick to Paphos but in Paphos there was no visa. They put me in the room with police and called in my friend who had come to collect me. He enters and says ‘do you know who this girl is? She wrote this famous song’. The policemen started crying, apologising… They found my visa…it was at Larnaca airport…

“Afterwards, everywhere I went it was the same – my friend would say ‘do you know who she is’ and people would be so welcoming. Then they invited me for an interview at CyBC and I told them about my dolls … Next day I had a phone call from a childhood friend in Peristerona. We used to play together when we were kids. Her parents had seen me on TV and asked her to give me something. And it was some of my family’s belongings… And later some other people also did the same…”

However, all this lay ahead.

Back to the 1970s, when Nese attended the Turk Maarif Koleji, a school created in 1964 in north Nicosia as an equivalent to the English School. She read a lot, wrote poetry. Then she left for Ankara to study sociology at University. And it was there that the teenage Nese one fateful evening set off for a poetry reading in the course of which she plucks up the courage to ask Behramoglu to look at some of her poems.

While Nese’s poem was making the rounds in the south to the point it became one of the unofficial anthems of the 1980s (during the 1991 performance Tokas says that even though it had never been recorded everybody knew about it) Nese married.

“I didn’t really want to marry so young but when my mother died my sister was only eight and she came to live with me in Ankara,” she explains. She had a son but the marriage wasn’t going well and divorce soon followed.

Nese packed her bags and with her son returned to Cyprus, looking for a job. However, she had become an activist in Turkey, a writer involved with the left and this was not something the authorities in north Cyprus were very happy about. Neither did they like her involvement in bicommunal activities. Finding a job proved almost impossible. She wrote poetry and articles, even opened a small coffee shop to survive… Her financial situation was so precarious she was driven to sending her son to her ex-husband in Turkey.

In 1993, Yasin found herself in even deeper waters. In Famagusta she met Salih Askeroglu, a Turkish Cypriot man in love with a Greek Cypriot woman who had moved to the north for him.

“Salih was called up to the army and decided he didn’t want to go because he didn’t want to be in a situation where potentially he could have been forced to use his gun against Yota’s father or brother. He was the first in the north to declare himself a conscientious objector and I, along with a group of close friends, decided to run his campaign.”

A young Nese with her-brother

The authorities acted swiftly. They arrested Salih, deported Yota and their newly born baby to the south and jailed Nese for “helping Salih and working against the military”.

Nese was a familiar figure in the global writers’ community and word of her plight quickly spread. Almost immediately, the fax machine in the office of then Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktash was jammed with protests from individual writers, the international PEN association and sympathetic politicians.

“They let me go after 16 hours but decided to follow me everywhere. And when I complained about it they said I should think about is as a kind of bodyguard. I told them I would prefer Kevin Costner,” laughs Nese.

Despite these heart-warming moments of communal solidarity, Nese could feel the mounting pressure. The Turkish military was against her, the secret police was spreading nasty gossip about her, the nationalist newspapers were publishing insulting articles.

“I was a single woman, a poet. I didn’t have a job. I had no property – no car that they could plant a bomb under. My son was in Istanbul. There was a lot of pressure. I felt like persona non grata.”

Her friends in the south pleaded with her to move there. Finally, she did. “So I went to the south.

“I had friends in the south, many friends. There were some Turkish Cypriots living there and also I knew many people from my bicommunal activities, so I was surrounded by very nice people. And some people just embraced me – I was like a jewel for them… But of course there were also some others for whom I was just a Turk. And needless to say I was missing my friends on the other side and my son in Istanbul. In fact I was flying to Istanbul via Athens all the time.”

Nese got a job at the Department of Turkish and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cyprus, despite objections on the part of some that she didn’t speak Greek, and she found herself a flat in the same building as some of her closest friends.

She was constantly visited by a stream of foreign journalists, all seeking to meet the “famous” Turkish Cypriot poet who had moved to the south. But, it was an ordeal she found to be “very tiring”.

She persisted in flying back to the north via Athens and Istanbul, the expensively incongruous routing available pre-2003. Yet, it was not until the first crossing opened in Nicosia that she found herself fully re-united with “both sides of herself”. Her whole life changed when the crossings opened. “It was actually not only psychological, it was also physical – my whole body relaxed.

“It was a good decision. My whole life looks different because of it. Even if I hadn’t come here [to the south] I wouldn’t stay there… maybe I would have gone to Istanbul… and for sure I would have got myself in trouble there too. I was always a rebel. All my life my main urge was freedom… Here at least I was more protected…”

So what plans does she have for the future?

“Well, I am retiring this year from the university and then I will have more time for writing,” she says and her face lights up with that warm Nese smile. And I am looking at the beguiling smile of Nese the rebel, the poet, the eternally young woman from Peristerona.

Click here to change your cookie preferences