Never letting your reader know quite what’s going in is a fairly standard formula for the generation of unease. Sarah Bernstein’s second novel is high on unease. It’s also high on pretty sentences. The first issue is that this might really be all there is. The second issue is that I just can’t make out whether this is enough.

Let me explain. This is a book in which the narrator is everything. An unnamed young woman who moves to a nameless northern country to resume a life of servitude to her eldest sibling that was begun, by her own account, from birth. Our narrator’s speciality is reduction: her childhood taught her to ‘become reduced, diminished… clarified, even cease to exist’. She tells us that getting through the airport is unusually challenging because airport scanners refuse to pick up her presence, and later declares herself ‘evidently not a main character’. The obvious irony of this statement in a book in which she is almost the only character begs the question of how far we can trust her. But this also remains unanswered.

We don’t know if she is the victim of a cruel and abusive childhood; we don’t know if she harbours incestuous feelings for her brother; we don’t know if there is any justice to the way the locals seem to blame her for the various unsettling events that start to take place in town after she arrives; we don’t know whether her brother’s ailing health has anything to do with the medicinal herbs she picks in the forest; by the end we have no idea who is or was ever really in control.

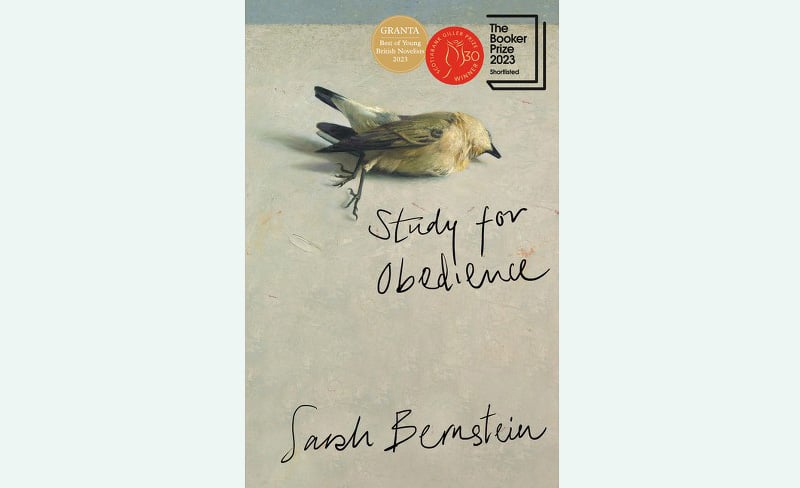

This is cleverly done. And if we think about the book as one about how victimhood and abasement can linger and harden and change into a kind of negative egotism or a sublimated vengefulness, we can make sense of the way it deliberately withholds and sows doubt. But you have to think so hard about it that it feels like you’re doing the book a favour. And it’s not a favour I can really be sure it deserves. If you decide that the book is asking more than it’s worth your while giving, then you’re left with what we started with. Unease and pretty sentences. If that sounds like enough for you, then you’ll have a lovely time with Study for Obedience. If not, I’d suggest there are more satisfying ways to be unsettled.

Click here to change your cookie preferences