By Duncan McCowan

I’m very fortunate to have a large garden, about an English acre, secreted between Dali and Potamia, and bordered by the seasonal Yialyas river. I’m doubly lucky in having no human neighbours.

Anyone with a garden is fortunate, and never more so than at this time of year in Cyprus, when we are unsurprised by the knowledge that ancient fertility cults arose in this region of the world. All around us Aphrodite is sprouting from the primordial froth. And for someone with an interest in flora and fauna, springtime and summers are seasons of joy.

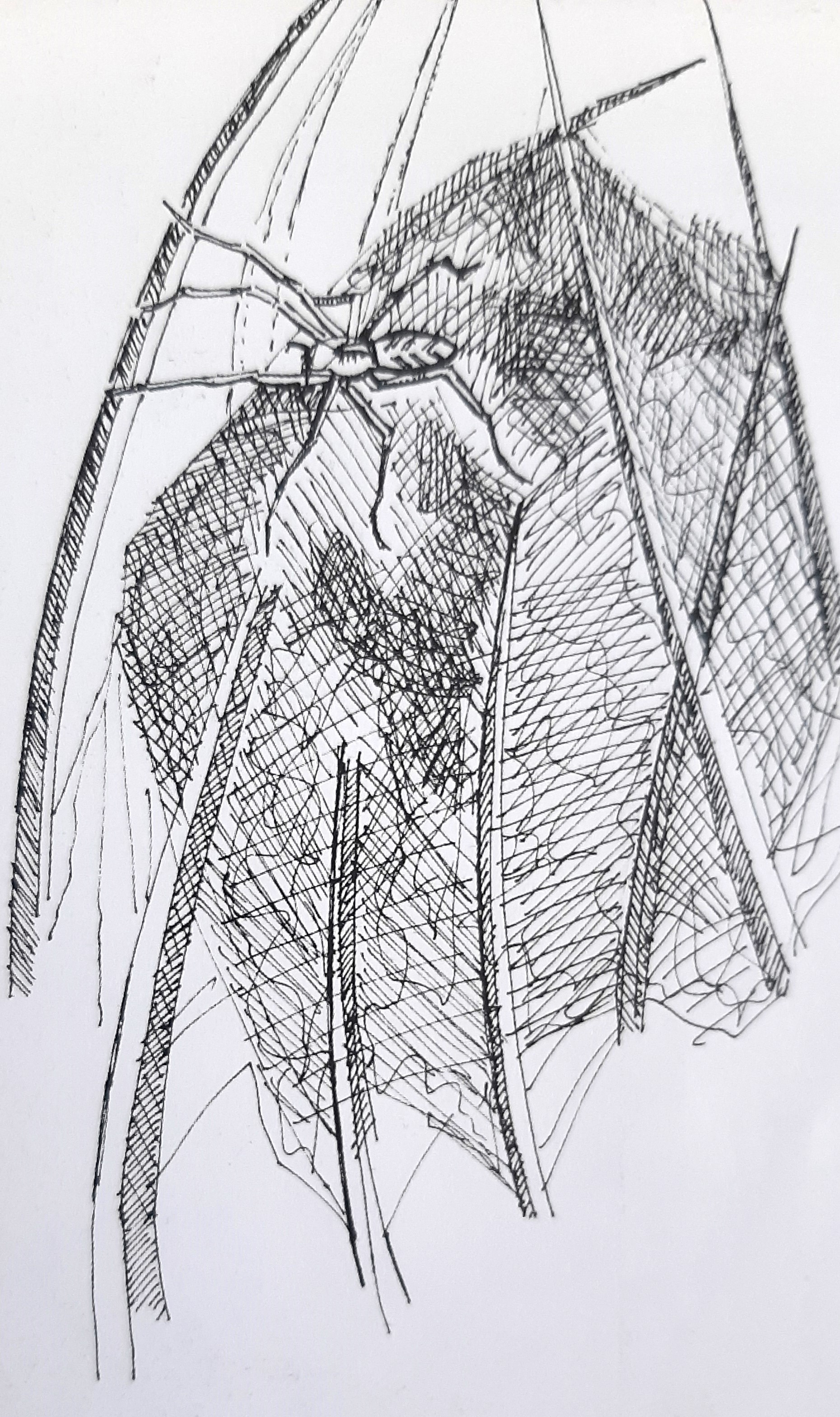

Not everyone likes spiders, but I do. I enjoy observing and noting their habits. My social life has sometimes suffered accordingly, but it’s a sacrifice I’m happy to make. A human conversation can seldom compete with the allure and fascination of eight-legged antics. With this in mind, and because it is very likely that certain characterful spiders have already set up camp in your own backyard, it seems right to draw your attention to them, and perhaps win some converts along the way.

Many spiders are marvellous, but there is one that is also in name, Pisaura mirabilis, the Nursery Web Spider. This is a sleekly handsome, fawn-coloured species of medium-size with some notable habits. If ever we are inclined to assert our superiority to the beasts of the fields, then a closer look at this arachnid will quickly remind us of how primitive and lowly we all are.

The courting habits of mirabilis are uncannily familiar. The males, which are slightly smaller than the females, reach maturity one or two moults before the female does. This gives them the chance to hunt down females and wait for them to complete their final moult before approaching them. The male has already charged his pedipalps, the two now swollen appendages extending from the cephalothorax (head), with semen. He is ready to make a charge and hopefully catch his mate in a semi-pliant post-moulting state, and thus increase his chances of survival. Male spiders mate at their peril, since the female might decide she feels more hungry than aroused, and even if she allows the male to couple, she might have a mid-copulatory hunger-pang and decide to feed on him anyway. (Many species of spider practice sexual cannibalism, the Widow spiders, of which we have three species in Cyprus, are renowned for it!).

This androphagy has the added bonus of providing a timely dose of protein prior to pregnancy. But Mr Mirabilis has a card to play that marks him as a smooth operator. Before approaching the female he captures a succulent prey item, a fly mostly, wraps it in swathes of irresistible silk, and then offers it to the haughty female. Just like a box of Milk Tray chocolates. What makes this courtship all the more remarkable is the pose that the male strikes in order to signal his gift to the female. Holding the package between his fangs he lowers his abdomen until it is perpendicular to the ground, at the same time he raises his pedipalps and front pair of legs in the air above his head in a weirdly symmetric yogic pose, and looks, frankly, ridiculous.

Depending on her mood, she may accept the nuptial gift along with the male’s advances, but he’s never easily convinced of her favours. Just in case, he has another tactic devised to enhance his longevity. While she feeds on her gift, he slips beneath her and begins to insert his pedipalps into her epigyne, the female genital opening, all the time keeping one leg on the wrapped gift. The process can last up to an hour. If he senses that she might be more impressed by his own corpulent abdomen than the gift, he rapidly feigns death, employing thanatosis as a survival technique. In this pseudo catatonic state he can be dragged around by the stronger female until he can make a dash for it. This behaviour has been shown to increase the chances of male mating success from around 30 to 90 percent. As a rule, and typically with spiders there are always exceptions, spiders do not usually predate dead creatures.

I was once lucky enough to witness a contest between two attendant males trying to impress a female on my veranda floor. It was a very human scenario. Each male spider brandished a gift, each waited for the other to make a move. Neither seemed wholly convinced of their prospects of success. One inched forward, trying to outbid his adversary, while keeping several close eyes on the expectant bride and the remainder on the competing male. Spiders can do this, they mostly have eight eyes. The female took the gift ravenously in her jaws, allowed the male to approach, and then unceremoniously chucked the package over her body and bit the male’s head off in one expert move. She then charged at the remaining male, who stood transfixed and trembling behind his bundle. She took it, allowed him to mate, and then ate him too. What a wedding feast! It was like a scene from The Silence of the Lambs in miniature.

And so you ask, why then “Nursery Web Spider”, with all its comely maternal associations, after having described such a ruthless, cold-blooded serial-killer? Well, good mothering needn’t be impaired by a person’s bedroom habits. Pisaura mirabilis, like many female spiders, is an exemplary mother, just as the male is an extraordinary suitor. In the female body there are twin receptacles for storing semen after insemination, spermathecae. She needs only to mate once to have a store of sperm to fertilise all the eggs she produces at her leisure. These fertilised eggs (up to 300!), she wraps in several layers of silk to form a whitish pea-shaped egg-sack. This cumbersome baggage is then carried around by the female wedged between her mouth parts, chelicerae, and her lowered abdomen, like an over-sized beanbag. When the eggs are ready to hatch, having moulted once inside the sack, she attaches it to a blade of grass and begins spinning a “nursery web” around it, a protective spherical awning over which she stands guard while her brood eventually emerge and play happily together until the second moult, after which they tend to view their siblings as potential meals. At this point nature wisely prods them to disperse.

So, if you find yourself at a loss for entertainment of an afternoon in May or June, and happen to have a grassy meadow on hand, treat yourself to nature’s Netflix by seeking out Pisaura mirabilis watching over her nursery of acrobatic arachnids. The marvel in your garden.

Duncan McCowan is a teacher of English with an interest in Cypriot spiders. He has lived in Dali, his grandfather’s village, since 1991. His book 60 Cypriot Spiders is available from bookstores island-wide

Click here to change your cookie preferences