Deliberately smashing plates in restaurants, duelling and telling fortunes are all illegal and are humorous, but some of the colonial holdovers are a bit more sinister

“Any person having in his possession, custody, control or disposition any sponge, knowing that it has been taken in contravention of this Law, shall be liable to a fine not exceeding twenty pounds, and the sponge shall be forfeited.”

That’s Cap. 146, the Sponge Fishery Law, part of the so-called Chapters which remain part of Cyprus law, despite being antiquated.

This is the colonial system that the Republic inherited upon independence – and, though it’s slowly being updated, change has been piecemeal.

Some of the old British laws have been repealed, most have been modified – but, for instance, the Sponge Fishery Law remains in force (barring a small, cosmetic update in 1968), even though we no longer have a sponge-fishing industry.

Cap. 146 – like Cap. 145, the Silkworm Industry Protection Law, banning the import of silkworms into Cyprus – is part of the least concerning tranche of obscure laws, a law so obsolete it’s become irrelevant. They clutter up the statute book, but don’t really do any harm.

Who could object, for instance, to a law obliging a purchaser of carobs to weigh the sack containing the fruit separately from the carobs themselves, if required to do so by the vendor? (Cap. 37, Carob Tare Law)

Other times, a law might fall into disuse then suddenly get dragged back in the spotlight – at which point its outdated nature becomes a problem.

That’s what happened four years ago with Cap. 260, the Quarantine Law dating back to 1932, which was pressed into service to deal with Covid restrictions.

The old law was clearly inadequate, forcing a scramble to pass amendments to create legally binding new penalties – not to mention changing the currency in which fines would be paid from pounds into euros. In the end, most of the fines remained unpaid, and the legality of the whole process was widely challenged.

Laws reflect society, but don’t change as quickly or nimbly as society – which is why we still have laws that “reflect social norms and conditions from the past”, as Nicosia lawyer Pantelis Christofides told the Cyprus Mail.

Most of these are in Cap. 154, the Penal Code – which of course gets updated more than any other law, but still contains some weird anomalies.

Thus, for instance, we have Article 97, regulating the holding of Moslem [sic] feasts:

“Any person who holds or is responsible for a Moslem feast… and engages, whether with or without pay, or knowingly permits a dancing girl to dance or sing at such feast, is guilty of a misdemeanour.”

What a party pooper of a law, eh? One may surmise that ‘dancing girl’ is a euphemism – but in fact that’s only half-right. “In this section ‘dancing girl’ means a prostitute,” admits the article – but then adds, “or a woman who dances or sings for pay at Moslem feasts”, which just seems like circular logic but whatever.

Speaking of feasts, and getting in the way of a good time, Article 95(A) has this to say:

“Any person who, in a public place of entertainment, purposely breaks any item of tableware made of glass, porcelain or any other fragile material, is guilty of a misdemeanour and liable to imprisonment for six months.”

Six months for smashing plates in a bouzouki place sounds excessive (and would surely come as news to Greek restaurants in the UK, for whom it’s often a selling point). 95(A) was actually added post-independence, not being part of the original criminal code. One wonders what happened to raise such an outcry that lawmakers felt compelled to create it.

Quite a lot of things are actually illegal in Cyprus, which you wouldn’t necessarily expect or imagine.

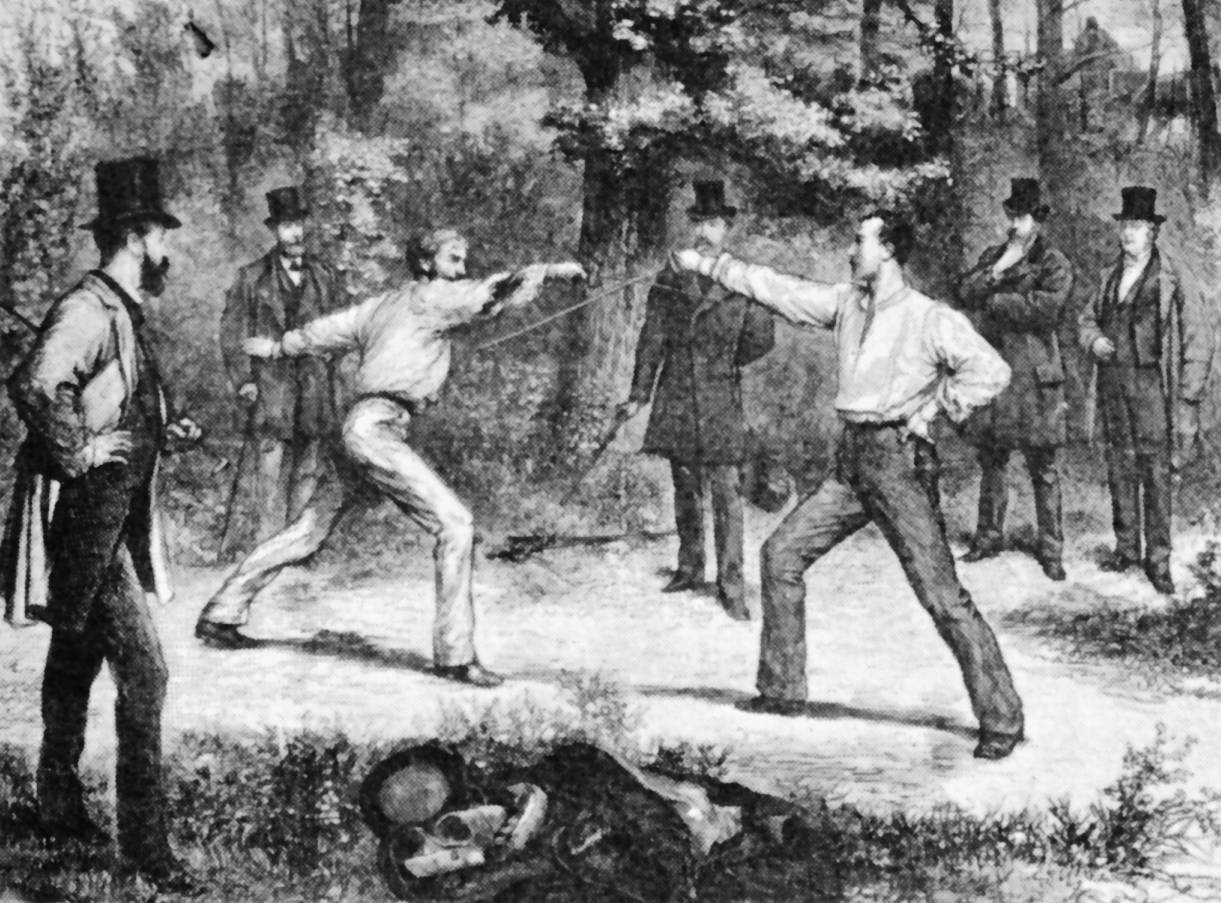

Article 90 makes it illegal to challenge another person to fight a duel, or even to attempt to provoke another person into fighting a duel.

Article 304 makes it illegal to tell people’s fortune, or to “pretend to exercise… any kind of witchcraft, sorcery, enchantment or conjuration”. It’s unclear what happens if the accused claims they actually were exercising these things, not just pretending to.

Article 178 covers the somewhat unusual case of a person who “wilfully and by fraud causes any woman who is not lawfully married to him to believe that she is lawfully married to him, and to co-habit or have sexual intercourse with him in that belief”. This, needless to say, is illegal – though the law isn’t gender-neutral, so ladies can presumably get away with this dubious behaviour.

Article 99(B) – also added recently, in 2018 – makes it illegal to obstruct a mother from breastfeeding, whether by word or gesture or in any other manner.

Cap. 196, the Coinage (Protection) Law, makes it illegal to “melt down, break up or use otherwise than as currency any coin which is for the time being current in the Colony [sic] or in any other country”.

The law on knives seems especially draconian. Article 82 of the penal code makes it an offence – liable to a year’s imprisonment – to carry a knife outside your home, even when the knife doesn’t end in a sharp point. (Are blunt knives really so dangerous?) That said, Article 84 makes an exception for some clasp-knives or folding knives.

Finding weird laws is a fun little game. (One could also mention Cap. 304, the Submarine Telegraph Law, making it an offence to “break or injure any submarine cable”.) In practice, however, such laws are seldom applied, even when enforcement is theoretically possible.

“The legal service aren’t stupid,” notes lawyer Kriton Dionysiou. “They’re not going to charge just anyone.”

The bigger danger, when it comes to getting tripped up by things you didn’t realise were illegal, actually comes less from antiquated laws which are no longer relevant than from new laws which are too broadly drafted.

Dionysiou points, for instance, to Article 7(3) of the law on harassment and stalking (Law N. 114(I)/2021), which applies a reasonable-man test to what constitutes harassment.

“A person shall be deemed that he ought to know that his course of conduct amounts to harassment or stalking,” it reads, “if a reasonable person under the same circumstances would consider that this course of conduct amounts to harassment or stalking.”

Is this fair? Should someone be guilty of harassment even when they genuinely never intended to harass anyone, just because a ‘reasonable person’ (whatever that means) might have felt differently? Laws on hate speech and causing offence are also notoriously slippery.

In the end, laws reflect society – and some of our own laws will probably seem just as weird 60 years from now as some of the Chapters do today.

Click here to change your cookie preferences