A mecca for climbers, hikers, geologists and nature lovers today, the Troodos mountain range is the backbone of Cyprus ever since it was formed 92 million years ago as a fragment of an ancient oceanic crust.

Beyond shaping the island’s topography and natural history, it is also home to the copper deposits that, for centuries, played such a central role in the island’s economy and connected Cyprus to broader networks of international trade. Even Cyprus’ name itself could be linked to an ancient word for copper.

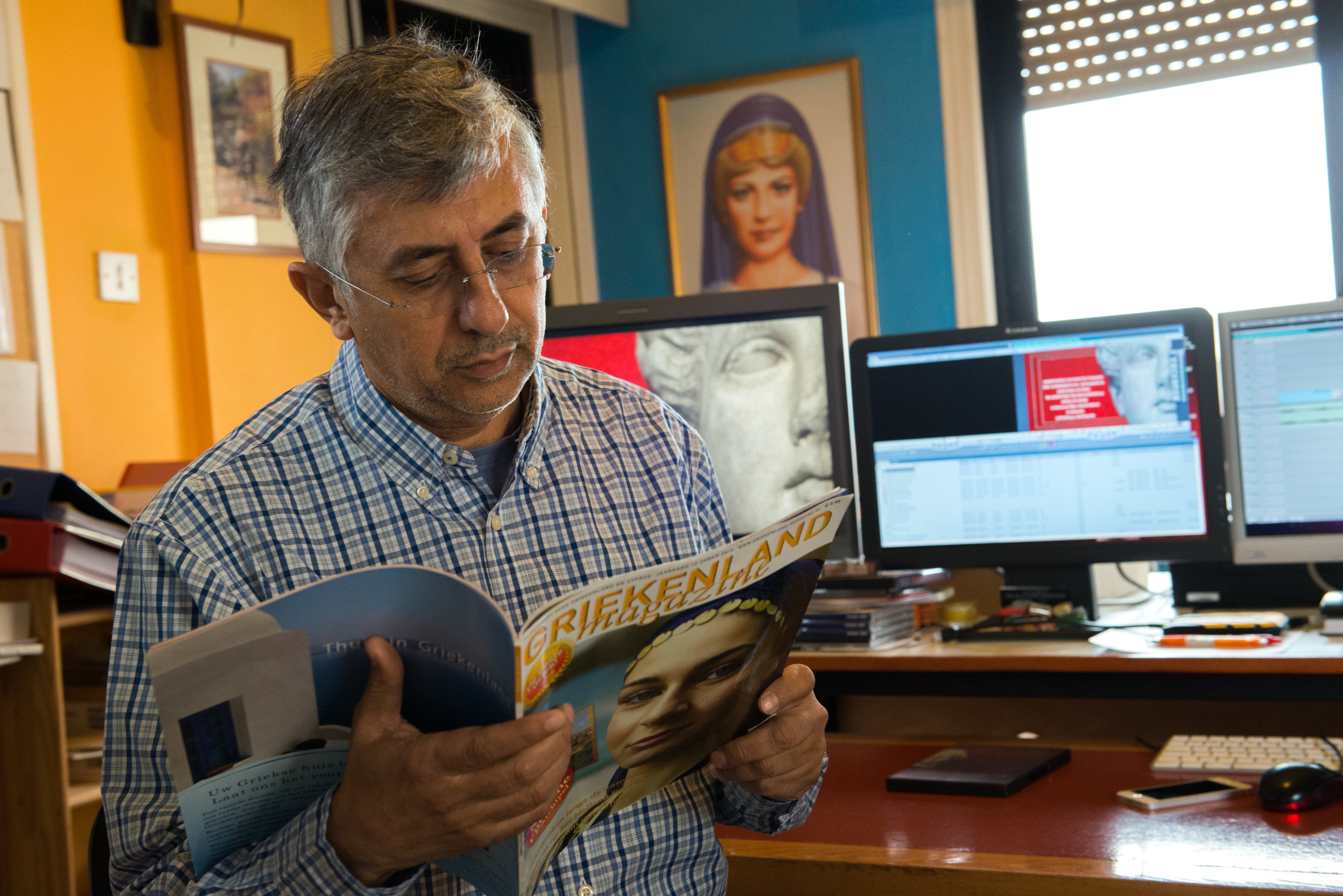

Filmmaker Stavros Papageorgiou, who has dedicated the last 40 years of his life capturing Cypriot history, explores the enduring influence of the rust-red mineral in his latest new documentary “The History of Copper in Cyprus”.

‘All the copper that you desire I will send you’

“Geology and archaeology are among my main interests,” says Papageorgiou, clearly excited as he talks about the two topics he mostly covers in his work. He mentions some of his earlier projects like his film on Aphrodite and “the legendary king Kinyras of Cyprus”, as he calls the ruler who governed the island around 1560 BC.

As history tends to be told through the legacies of kings and emperors, yet another royal presence emerges when taking a closer look at the legacy of copper in Cyprus: Kushmeshusha, the king of Alashiya, commonly regarded as Cyprus in the second millennium BC.

While the exact period of Kushmeshusha’s rule remains undetermined, his significant role in trade and diplomacy, as indicated by clay tablet correspondence with the Pharaoh of Egypt, points to his rule in the late 13th century BC.

“Send your messenger along with my messenger quickly and all the copper that you desire I will send you, my brother. You are my brother; you should send me silver, my brother – a great quantity. Give me the best silver, then I will send you, my brother, all that you, my brother, request,” says Kushmeshushas in a clay tablet to the Pharaoh dated between 1375 and 1335 BC.

Through these historical records, Alashiya’s pivotal role in the economic landscape of the Eastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age becomes clear, with copper trade standing out as a key element exported not only to Egypt but also the Aegean and Mesopotamia (modern Iraq).

Historical significance of copper

With the letters highlighting Cyprus’ powerful role in the global copper trade of the time, it is time to turn our attention to the internal dynamics of copper production and its use within the island itself.

“We have ancient mines that were active from the Bronze Age to the late Roman Period, and then we have the modern ones that started in the late 19th century,” Papageorgiou says, “yet the late Bronze Age clearly was the peak time of the history of copper in Cyprus.”

Among the general population, copper found a wide range of uses, Papageorgiou explains.

“Cooking utensils, jewellery, surgical instruments – copper was a commodity that had a significant value,” he says.

Even now, antique copper cooking utensils are still a common feature around the island.

Most of the ancient copper-related artefacts in Cyprus were discovered in tombs, with Papageorgiou referencing one in Paphos believed to belong to a Roman surgeon.

Archaeologist Demetrios Michaelides, professor emeritus at the University of Cyprus, who took part in the excavation of the tomb in 1980, offers further insight.

“We are talking about a notably well-equipped surgeon,” Michaelides says. In the tomb, the researchers found bronze tubes with powders believed to have been used as medicine – all of them being byproducts of copper.

Michaelides then points to renowned Greek physician Galen who recognised the medicinal value of Cypriot copper resources during his visit to the island around 166 AD.

Galen specifically sought substances from the mines of Soloi in Troodos, bringing various copper ores such as misy (chalcopyrite), sory, and khalkanthos (copper sulphate) for medical use from there.

Aside from powders, Michaelides says copper derivates for medical use were often mixed with wine or fruit juices to treat a variety of medical issues such as stomach pain or worms. “Copper is a highly antiseptic mineral,” he says.

Cypriot copper under foreign rule

Under Roman rule, copper extraction in Cyprus was tightly controlled by the emperors, who oversaw its use primarily in paying soldiers with coins made from copper.

“No one could exploit copper without their permission,” he says, highlighting how the resource was tightly regulated under imperial authority, “the same goes for when Cyprus was under the rule of the British.”

Modern mining in Cyprus, Papageorgiou says, began when the British came to the island. “We also had a few individuals, like Gunther and others, who came specifically to exploit copper,” he adds. With this, Papageorgiou refers to Charles Godfrey Gunther, an American prospector that arrived in Cyprus in 1912, whom the filmmaker calls “the Indiana Jones of the mines”.

After a peak of modern mining in the 1950s and 1960s, falling international copper prices led to a halt in the Cypriot mining industry by 1979, though in the 1980s, some companies began recovering copper from leaching waste – a method applied again at the Skouriotissa mine which reopened in 1996.

Copper in modern-day Cyprus

Today, the remnants of 23 former mines can still be found across Cyprus, including Skouriotissa.

Current Deputy Culture Minister Vasiliki Kassianidou, formerly an archaeologist at the University of Cyprus, has extensively researched copper mining on the island. In one of her studies, she notes that in fact the very name Skouriotissa is connected to Cyprus’ copper history as it comes from the Greek word skouria meaning slag from smelting furnaces.

Kassianidou explains that in the area, slag heaps became such a dominant feature that they even inspired the name of the Monastery of Panagia Skouriotissa – essentially meaning the Virgin Mary of the Slag.

Along with Mavrovouni and Apliki, Skouriotissa produced more than 85 per cent of Cyprus’ total copper ore concentrate in the 20th century, and in the 21st century, 100 per cent of the island’s exported copper metal came from Skouriotissa.

However, not everyone supports the continuation of mining with environmentalists voicing concerns over machinery to exploit copper kicking up dust that pollutes the air and chemicals used to leach minerals contaminating waters.

In 2019, a bi-communal protestwas held against the use of cyanide at the Skouriotissa mine, underscoring growing environmental concerns surrounding the resumed operations at the site

Yet copper undeniably marks an important part of Cypriot history, that those eager to experience Cypriot copper legacy up close still explore today. Beyond museum displays, Troodos geopark offers direct access to its mining past.

“The mines in Troodos geopark are generally accessible to the public,” Papageorgiou says, urging visitors to tread carefully, as the area is not entirely safe.

“There you will see the craters of the abandoned mines, filled with striking red water at the bottom which looks like blood,” he says, warning that the water was in fact highly acidic. “Don’t dare put your finger in there,” he laughs.

This reflects the deep-rooted connection to this valuable metal with copper having shaped Cypriot history for centuries, leaving behind a lasting legacy and industry that continues to define the island today.

A first screening on Wednesday May 14 in Nicosia is almost fully booked. The History of Copper in Cyprus, directed by Stavros Papageorgiou, will premiere at the Nicosia Municipal Theatre at 7pm next week. Entrance is free. Film is in Greek with English subtitles. More screenings are planned

Click here to change your cookie preferences