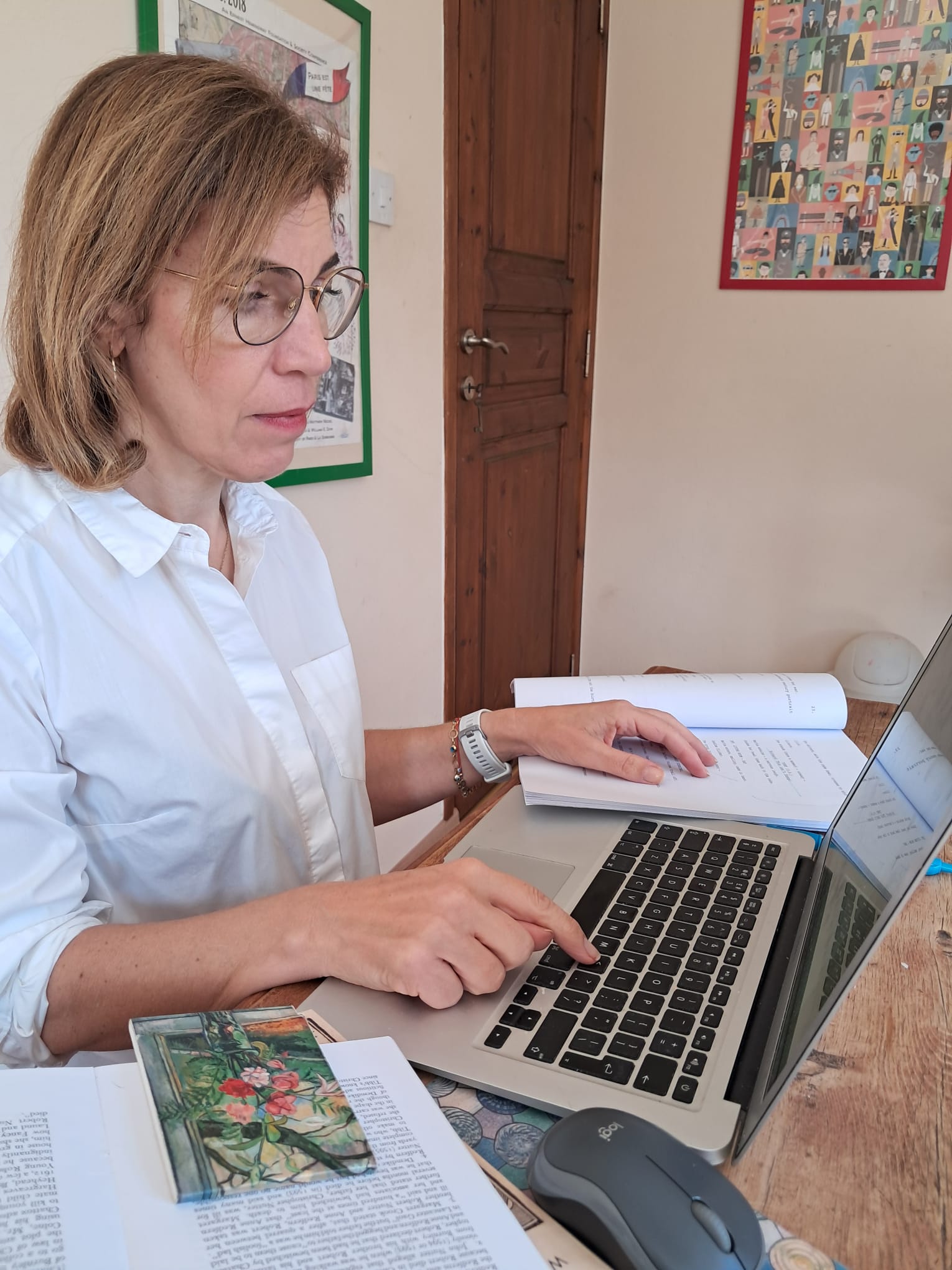

Selma Karayalcin is a mother, wife and full-time teacher. She has also just completed a horror film screenplay

Everyone, so it’s often claimed, has a book in them – or a script, or a play. The idea of being a writer is a potent one, creating something that’ll last – unlike the pointless, Sisyphean routine of a nine-to-five – and harnessing the imagination, that most neglected part of our psyche.

Writing a screenplay is even more glamorous, adding the frisson of someday seeing one’s name on Netflix – and of course we’ve all heard stories of the unknown writer who becomes the toast of Hollywood. But how exactly – just in terms of logistics – do you juggle writing a script with working a full-time job? And once you’ve written it, what do you do with it?

If she were retired, “I’d be working from breakfast to night-time,” sighs Selma Karayalcin – and that’s how a lot of people do it, waiting for retirement to devote a lifetime’s worth of pent-up energy to their pet project.

Selma, by her own admission, is no spring chicken (she’ll be 54 this month), but she’s not prepared to wait for the quote-unquote ‘golden years’. She began writing scripts about eight years ago, has written seven so far – though a few are just first drafts – and now hopes to break out with her latest, a horror screenplay called Witch Mother which is garnering attention in the industry. At the same time, she’s been busy as a wife and mother (her daughter just turned 18) and also works full-time, as an English teacher at the English School, Nicosia.

Some may think that having a job related to language and writing helps – and it’s true she has experience of academic writing, having done a PhD and published papers in her pre-scriptwriter days. But being a teacher is actually a mixed blessing.

T.S. Eliot, to name one famous example, had a job in a bank – but when the bank closed each day, he was free to concentrate on his poetry. Selma, on the other hand, is “a teacher 24 hours a day. I’m taking the work home, I’m doing the prep. So trying to organise my time properly is very, very challenging”.

One detail makes it even more challenging. Selma, a Turkish Cypriot, grew up in London but has lived in Kyrenia since moving to Cyprus in 2000 – meaning she has to negotiate the checkpoints every day to and from work, an additional time-suck that’s currently worse than it’s ever been. (It’s getting so bad that she’s starting to consider alternatives, like using two cars – one on each side – or crossing at the Ledra Palace and taking the bus.) She leaves home at 6am, and just about misses the rush. If she happens to leave 10 or 20 minutes later, though, it becomes a nightmare.

Back in the day, when she first started scriptwriting, she’d only attempt it during the holidays (the one big advantage of being a teacher) – which worked for a while, but not really. Just as she’d start getting to grips with a project, school would re-open and she’d “drift back into school mode. Which is not a bad thing, obviously, but I was unable in the early days to balance both of them… I’d lose the momentum”.

These days, she incorporates writing into her daily routine – a much better system, but also exhausting.

She’ll wake up at five or thereabouts – then it’s “full-on school”, then domestic chores and family time, “I try to fit in a run, or go to the gym” (Selma’s a runner, which adds to the workload but also helps keep her sane), then in the evenings she gets creative.

“After dinner I’ll go upstairs. I’ll sit at the computer, I’ll look at the things I need to do – to do with pitching, and getting it out there… I lose myself in it. Then, before I know it, it’s about 11 o’clock and I’m exhausted.”

She’s not actually writing at the moment. Witch Mother is done – it was recently a Finalist in the prestigious 13Horror.com screenplay contest – but the process of trying to find a producer for the script (or just a manager who’ll promote it) is even more time-consuming, especially with the time difference. “So I’m pitching to people in New York at one in the morning, that sort of thing.” Then it’s to bed, and up at five again.

How then, just in terms of logistics, do you juggle a script with a full-time job? The answer seems to be ‘with great difficulty’ – or, more accurately, ‘with great determination’.

“I think everybody starts it,” muses Selma, speaking of the universal urge to create. “Everyone’s a starter – but it’s the finishing which is the real test…

“We’ve all got a story in us – yes we do! – and when I talk to my friends they all say, ‘Yeah, I’m going to write my life story when I retire’, or ‘I’ve already started’ – but then they don’t really go anywhere. ‘Oh, I don’t have time’… So it makes me think, ‘Am I selfish? Am I neglecting something?’ Why are we so different?”

She tries hard not to neglect the other aspects. Her husband is very understanding, but she still makes an effort to ensure they do “family things”, to make up for the hours when she locks herself away from the family. As for the times when screenwriting clashes with school work – grading papers and the like – “always it’s the screenwriting that suffers. Always”. She does take a little notebook to school, scribbling down stray ideas so she doesn’t forget.

Fair enough – but where does all this determination come from? What motivates her to keep writing?

“Because I’ve got a story to tell!” she blurts out. “You can’t even put it into words, it’s like, if I don’t do it there’s no point – no point being here…” She laughs, embarrassed. “I don’t know, that sounds so lofty and pretentious. I’m still trying to find the reason why I’m here – and I get very depressed about that sometimes. You know, ‘What am I doing? What am I doing with my life?’.”

Well… she’s a teacher.

“Indeed, indeed. It’s a privilege to teach those children, it really is. And I do love it… It should be enough, shouldn’t it?”

Maybe. Then again, the scripts are special – especially Witch Mother, which, despite being a “low-to-mid B horror film” in industry parlance, hits her in all kinds of personal ways.

Firstly, Selma’s late mother loved horror movies. “I grew up with my mum and my sister,” she explains, “and we were all avid film buffs.” Her sister died young, in a freak accident; she was also a writer, in fact “she was the talented one, not me”. All of Selma’s scripts, in a way, are a form of belated tribute to her loved ones’ memory.

Secondly, this particular script has a personal aspect, the idea having been suggested by her brother-in-law who’s a descendant of one of the so-called Pendle witches.

The Pendle witch trials of 1612 are a grim little footnote in British history. Twelve people in a Lancashire village were hanged for being witches – mostly on the testimony of a nine-year-old girl named Jennet Device, who purposely sent her mother and two siblings to the gallows along with her grandmother (who died in jail). Not only does it make a great story, but Selma’s brother-in-law also hoped – and hopes – that a film on the subject might spark a dialogue, and lead to the Pendle accused being pardoned.

Selma struggled with the script for three years, despite going to Pendle, doing research and reading the court testimony – and only really broke through when she decided to make not a period drama, but a horror film mostly set in the present day.

It’s now a film of two mothers (hence the punning title), with the vengeful spirit of Jennet’s mum coming back to take the soul of a modern-day girl, the whole thing being livestreamed by a social-media influencer.

The livestream angle was a challenge for Selma, who’s too wrapped up in her “cocoon” of school, scripts and running to pay much attention to social media (“I’m not very good with the Facebook”). Finally, however, Witch Mother was done – so what happens next?

This, too, is fascinating – not just the details, like the need to register the script at the US Library of Congress (she could probably have done it in Cyprus, but she’s trying to think globally), but also the existence of a whole online ecosystem catering to aspiring screenwriters, a reflection of just how ubiquitous is the urge to create.

First, she explains, “I decided to get a professional reader to read it”. She found him through Stage 32, an online platform aimed at connecting creatives. It wasn’t free (it cost about $200), but he gave her an hour of his time, going through the script and opining on what did and didn’t work.

Then came the contest, 13horror.com, geared exclusively to horror films – a good investment, since the script now has ‘Finalist’ on its pedigree. Then there’s the pitching, finding potential producers – once again through Stage 32, “but there are others, there’s Roadmap, all sorts of other places for unknown writers like me”.

Selma has contacted about 20 producers, some of whom have responded positively. She’s done pitches, sent her ‘logline’ and described the script in 10-minute phone calls. She’s also approached a few managers – and none have said ‘yes’ as of this writing, but “I am determined to make it”.

In the end, she says simply, “two things happen. You either give up, or you keep going”.

It’s a hard slog, especially for screenwriters. “With a novelist,” she points out astutely, “whether you’re published or not, you’re a novelist. [The book] is on the shelf”. A screenplay, on the other hand, is a blueprint, not a finished work. She calls herself a working screenwriter, “but at the same time, I’m not”.

Because none of them are actual films?

“That’s right. And so they don’t exist. And I’m constantly being asked, ‘Why don’t you just write a novel?’.”

People don’t get it – not because they’re malicious, just because writing is so personal, its importance so disproportionate. It’s almost like having a baby – except that everyone understands a parent’s love for the fruit of their loins, whereas few understand the writer’s pride in the fruit of their imagination.

“When someone asks ‘How are you?’,” muses Selma – “in the old days, like seven or eight years ago, I would say [excited voice] ‘Oh, I’m working on a script!’. And you feel their eyes glaze over, and you see they’re just…”

Fair enough, she shrugs: “Why should they be interested? But it’s not just that – it’s also like, ‘It’s nice that she has a hobby, it’s nice that she has time to do something like that’…

“People think it’s a hobby. And it’s not a hobby. And I have a lot of difficulty with that perception.”

These days, Selma Karayalcin seldom bothers to talk about her writing. She just does it, staying up in the evenings after dinner, juggling it between early starts, and checkpoint delays, and teaching class to sometimes-indifferent teenagers – a practical strategy “that’s made me feel even more isolated”, then again isolation is the artist’s lot. The only solution, as with so much in life, is to keep going – and indeed she’s already full of ideas for the next project.

“It’s so easy to give up,” she says ruefully. “It’s so easy to say ‘I’m so tired, I’d just rather watch TV’. Which I’ve done as well, there’s loads of times I can’t do it…”

Writer’s block is a real thing. “There are gaps,” admits Selma of her writing career – “but then something pulls me back.” It’s the urge to create, that proverbial book (or script, or play) that’s in everyone. A butterfly locked in its chrysalis of everyday tasks and nine-to-fives, bursting to come out.

Click here to change your cookie preferences