He’s no longer trying to validate the legendary city, but he’s working with a team that have uncovered something fascinating

The world is filled with sunken cities. One study has counted 2,600 in 19 countries – victims of the Great Flood myth that permeates various ancient cultures from the Sumerians to the Bible – or coastal cities deluged during massive quakes and other earth changes over millennia.

Cyprus is no exception. One such is the ancient port of Amathus, which has been turned into an underwater archaeological park near Limassol. Salamis also fits the bill with part of its remains submerged.

And more than 20 years ago, those who are interested in ancient myths became terribly excited when a young American researcher Robert Sarmast set off out to prove that Atlantis – the holy grail of sunken cities – was off Cyprus.

Sarmast managed to put together two expeditions with the blessings – and some financing – from the Cyprus government but the story ultimately faded and the location of Atlantis remains a mystery that still divides those in the “alternative archaeology sphere”.

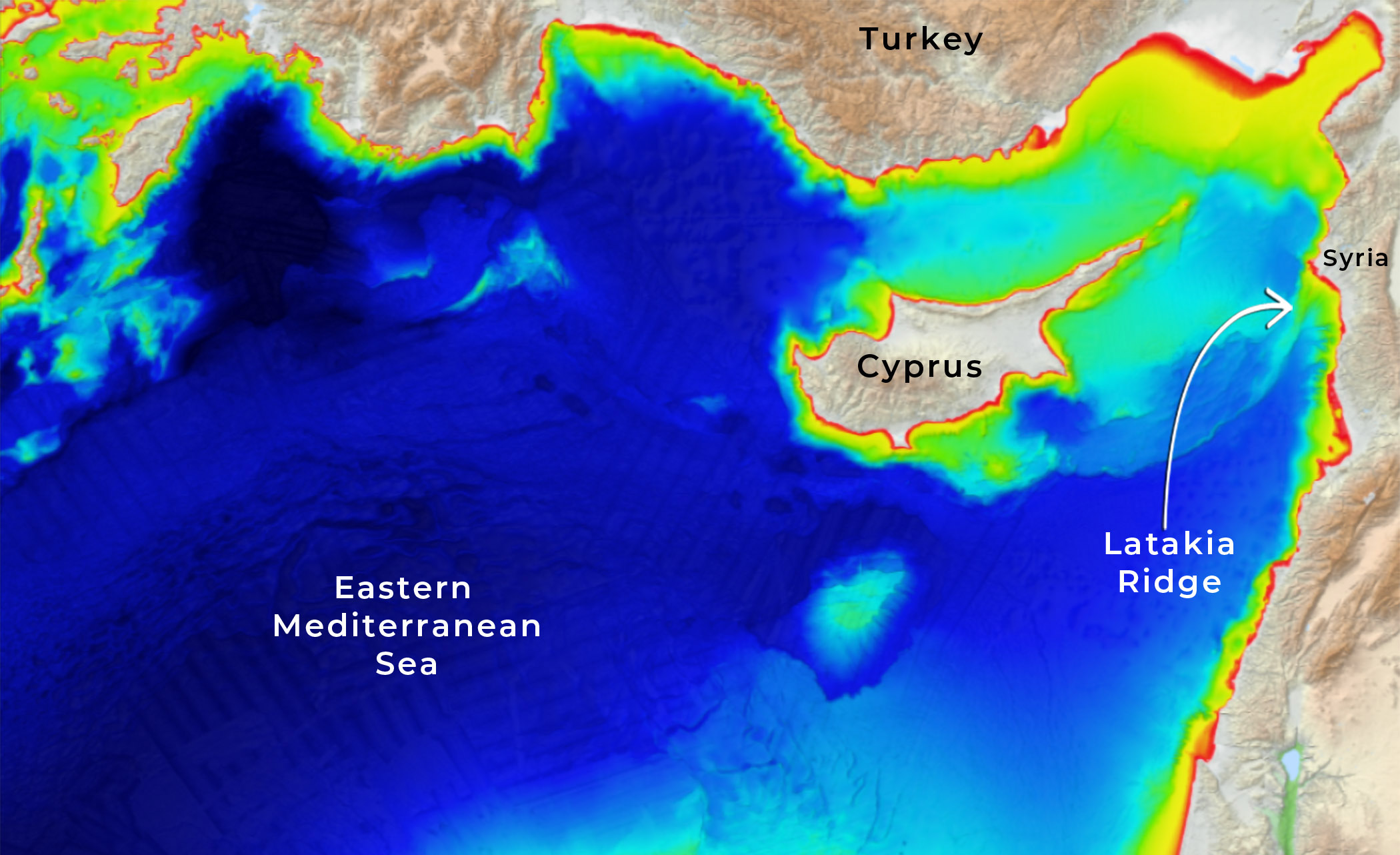

Well, Sarmast is back in Cyprus this month with a new book, new research and hopes of a new expedition to investigate what’s called the Latakia Ridge, which is some 20 miles off the coast of Syria but close enough to Cyprus to be deemed a significant link.

Atlantis gets nary a mention this time around as the focus is on determining if the structures captured twenty years ago are man-made.

“The term ‘Atlantis’ is loaded with mythology,” says the blurb on the website sunken-peninsula.com, set up by the Latakia Ridge Research Institute (LRRI), which doesn’t want the project to be perceived as Atlantis: The sequel.

“We are not claiming to have found Plato’s Atlantis or any specific legendary city. We are focused on a single, well‑defined anomaly on the Latakia Ridge that may be natural, artificial, or something in between. The goal is to test clear hypotheses with data, not to validate a legend,” the website adds.

Aw.

Still Sarmast believes there is something there of note and needing investigation. He gave a lecture at the University of Cyprus earlier in the week to launch the new project, and his new book: The Sunken Peninsula: An Astonishing Underwater City at the Latakia Ridge.

During his lecture, Sarmast unveiled never‑before‑seen, AI‑enhanced underwater maps that appear to show a highly geometric structure preserved half a kilometre beneath the sea on the Latakia Ridge between Cyprus and Syria.

It was only through the use of modern AI tools that the candidate site could be reliably identified with a simple instruction to “find what doesn’t fit the background geology”.

The details are technical but multiple independent datasets confirmed that these patterns were not mapping errors.

“We are not announcing the discovery of a lost city,” Sarmast said. “We are announcing a very specific, highly geometric anomaly that we can’t yet explain – and we are inviting the scientific community to help us test it.

“At this point, the only honest position is that we don’t know,” Sarmast said. “If this structure turns out to be entirely natural, it will still force us to rethink how such geometry can arise on the seafloor. If part of it proves engineered, then we have stumbled onto a chapter of human history that was literally off the map.”

The newly identified site lies a few kilometres beyond the area targeted during the 2004 and 2006 Atlantis searches, in a zone that earlier expeditions could not fully resolve with the technology then available. New, higher‑resolution maps and AI‑assisted terrain analysis have brought this region into focus for the first time, the LRRI said.

Sarmast’s book argues that if the Latakia Ridge structures are confirmed as engineered, they would support conclusions advanced by several Russian geophysicists in the mid‑20th century: that parts of the north‑eastern Mediterranean may have stood above sea level far more recently than mainstream Western chronologies have assumed.

The discovery carries potential implications for countries surrounding the Eastern Mediterranean — particularly Cyprus, which could find itself at the centre of a reassessment of the region’s ancient history and its role in the emergence of complex civilisation, he said.

In addition to the public lecture, Sarmast’s trip aims to initiate early planning for a new scientific expedition to be launched from Cyprus. The proposed mission would aim to obtain physical verification of the anomaly through core sampling of sediments coupled with high‑resolution multibeam sonar surveys and sub‑bottom profiling with visual ROV imaging.

“This is the kind of question that cannot be settled from a desktop,” said an LRRI spokesperson. “Either we will find a natural mechanism that explains everything we see, or we will have to confront the possibility of a deliberately engineered landscape that predates our current timelines for complex water management. In both scenarios, the data will be worth the effort.”

During his visit to the island, Sarmast expects to hold private briefings with scientific and regional representatives from Cyprus, Syria and Russia in the push to secure funding and permits for an expedition. The expedition could cost from the low to the high millions of dollars.

“We are not asking anyone to accept a lost civilisation,” said Sarmast. “We are asking them to look at a very specific anomaly and help us explain something that, so far, doesn’t fit any standard geological pattern.”

“The next step is straightforward field science,” he added. “Either we will find a natural process that explains this layout, or we will have to confront the possibility that someone was shaping this landscape before the sea arrived.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences