In his book The Forest & The Trees, musician and teacher Martin Bradfield provided an interesting analysis on the plight of more experimental and innovative drummers. “I can’t help but notice that a lot of the hardcore avant-garde players seem very unhappy, in print, in pictures, and in person. There seems to be a certain sense of bitterness in their tones. To be constantly criticised by the establishment, to be constantly battling the norm, must be a very defensive and lonely struggle,” Bradfield wrote.

Indeed, these elements, an anxiety to defend one’s principles and motivations, an undercurrent of acidity and feeling of persecution, and the threat of impending and potentially everlasting loneliness all feature in director Darius Marder’s film Sound of Metal. The film, available on Amazon Prime Video, follows drummer Ruben, played by Riz Ahmed, as he suddenly experiences an acute loss of his hearing. Ruben makes a living by touring America as one part of heavy metal duo Blackgammon, performing at shows and selling merchandise. Opposite Ruben is Lou, his partner and vocal performer, who is played by Olivia Cooke.

Marder’s direction choices firmly place the audience in Ruben’s shoes, or ears, rather. When his hearing first becomes affected, presumably by years of loud music enveloping him at shows, everything becomes dull and detached, noises turn muddled and faint, sloppily merging with each other in a background blend of hisses, rings and booms. We previously see Ruben being a man of precision, routine and discipline. Waking up at the crack of dawn to fix a fresh pot of coffee, healthy smoothies and do push ups, all before Lou has even woken up. There is an element of overcompensation and filling a gap, however, as we discover that Ruben had once been a heroin addict.

The spartan and at times raw approach to the portrayal of Ruben’s struggles is far from accidental, since Marder’s background in crafting documentaries informs how he chose to approach Sound of Metal. “I’m moved by things that grow from something that’s true rather than some kind of pretend world,” the director explained in an interview. When Ruben attempts to make a smoothie for a second time and after his hearing has been impacted, the blender, an appliance instantly associated with loud, grinding noises, becomes hushed.

The core of the movie deals with Ruben’s chosen path of recovery. Lou prevents Ruben from continuing to play music as it would only serve to damage his hearing even further. Not only that but she finds a shelter specifically designed to take in deaf addicts in recovery and provide support. Ruben does not easily acquiesce to this. “You need support,” Lou writes on a piece of paper. “What I need is a fucking gun in my mouth,” Ruben barks back.

Ruben’s recovery regimen includes sessions with young deaf children, ultimately involving the proficient drummer teaching them how to use a drumstick, not in a traditional drum set, but by hitting plastic buckets. This particular element brought back to mind an interview between deaf Scottish percussionist Evelyn Glennie and Mozarteum University in Salzburg.

Glennie was asked to opine on working with young children and how she perceived music as an activity, what it was composed of. “I think that to listen is something that is active. It is something that you require all your attention and the involvement of all your senses – hearing, sight, touch,” Glennie said. “The most important sense for a musician is touch.”

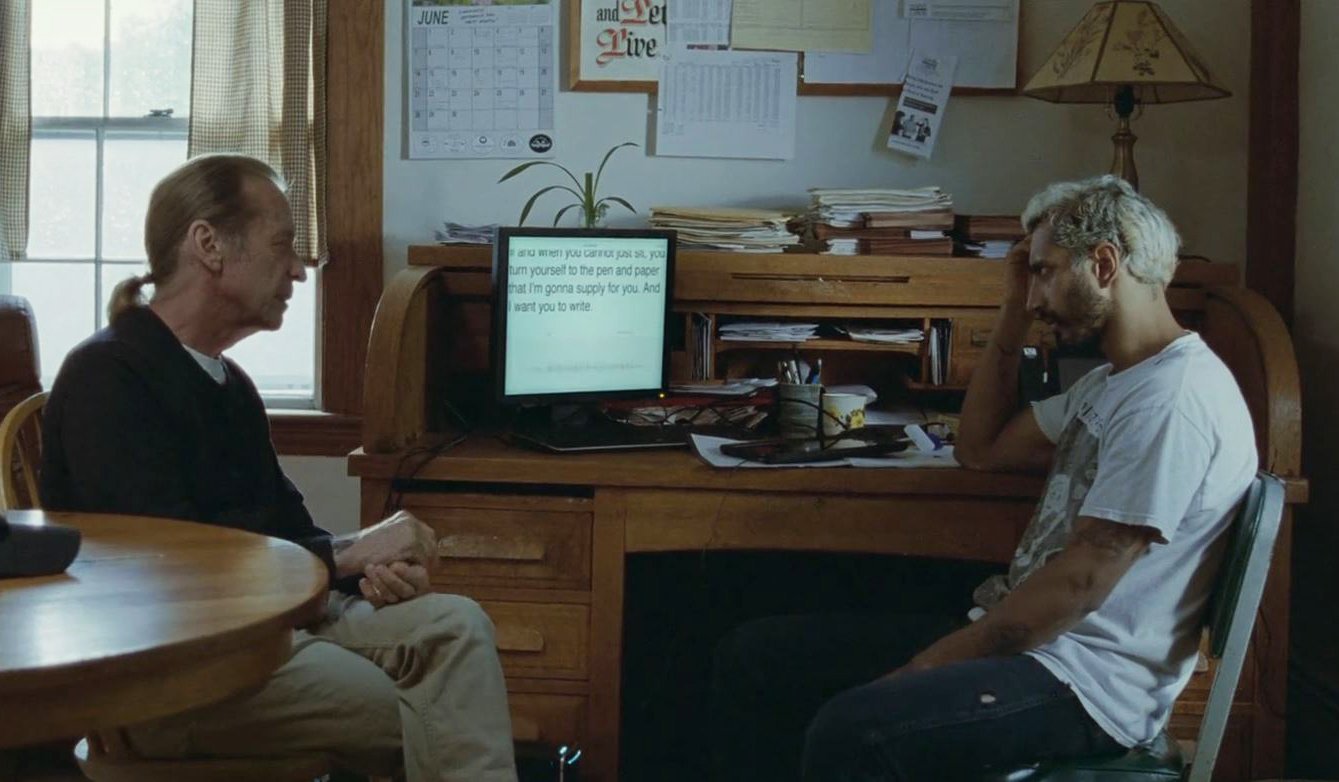

The shelter is run by Joe, a Vietnam veteran whose own hearing loss resulted in alcoholism and separation from his family. Truly, the interactions between Joe, impeccably performed by Paul Raci, and Ruben, are some of the strongest in the film. Ruben’s recovery includes an exercise in which Joe asks Ruben to be in a room by himself, accompanied solely by some blank paper and a pen, along with some coffee and a donut, the latter ending up as a stress ball of sorts in Ruben’s very first session.

Joe makes it clear that being able to be alone in serenity is crucial to Ruben’s recovery. “For me, that place of stillness that comes when I’m not clamoring, or running or desperately clutching…the moments where this crappy mundane world suddenly becomes radiant and magnificent, and all fear is gone…for me, that place is the kingdom of God.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences