Humanitarian disaster looms in Nagorno-Karabach due to blockade

By Costas Constantinou

In the backyard of the Mirhav inn, cats take turns climbing up to the windows to stare at the dishes of people breakfasting inside. They don’t seem to be hungry. It looks more like a drill against the snow and bitter cold of -6 degrees, even on this very sunny day in the Zangezur mountains that stretch around the inn and the town of Goris at this southernmost tip of Armenia, a stone’s throw on the map from Iran.

“Mirhav” means “pleasant”, and it is safe to say that both the inn and the picturesque region surrounding Goris have seen more far pleasant times than they are currently experiencing.

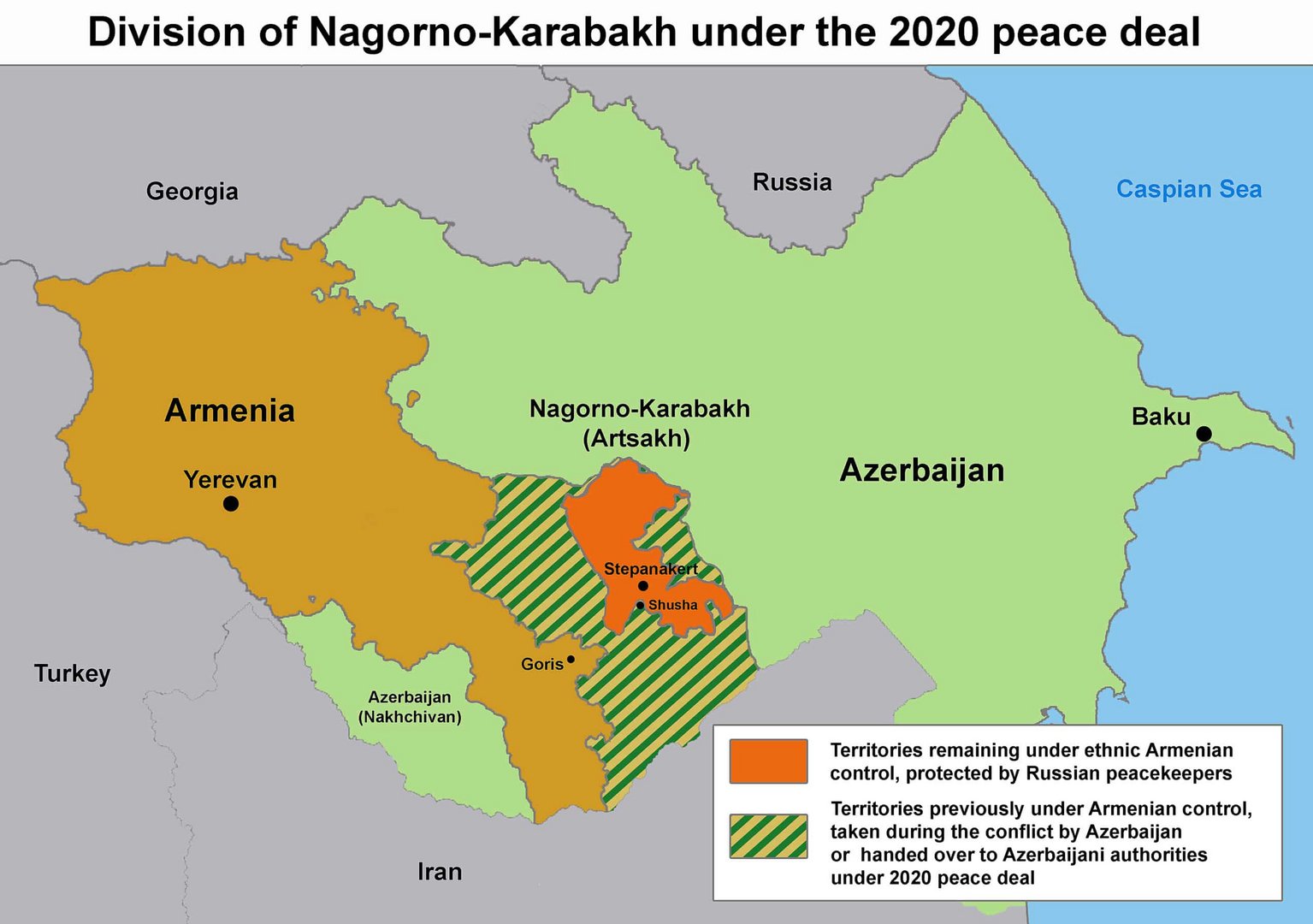

To get to Nagorno-Karabakh via the Lachin mountain corridor, one has to pass through Goris. There is simply no other way. It is a four-hour drive from Yerevan and another hour or so from Goris to Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, or Artsakh as the Armenians prefer to call it. This enclave within the territory of Azerbaijan, whose borders can be seen from the hills above Goris, made the news again in September 2020 when the Azeris attacked and seized several areas of the enclave following a brief war with Armenia.

The 2020 war was the biggest clash between the two parties in a conflict that had been regarded as ‘frozen’ since 1994, when a six-year war left all but one part of Nagorno-Karabakh under Armenian control. The crucial Lachin corridor is the only passageway between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia. Although many, and perhaps rightly so, disagree that this can easily be consider a frozen conflict, given the skirmishes and clashes that have erupted since 1994, two things remained largely unchanged since then: the territory of Artsakh under Armenian control, which however shrunk after the war of 2020, and the status of the Lachin corridor, which has been under the control of Russian peacekeepers. This is where the next, crucial and dangerous phase of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has been unfolding over the past few weeks.

Narine and her nine-year-old daughter have been living in the Mirhav inn since December 12. Her three other children – aged six, 14 and 17 – and her husband are in Nagorno-Karabakh. Narine had taken her daughter to see a doctor in Yerevan on December 10. When she tried to return home through the Lachin corridor two days later, Armenian border guards told her that the crossing had been blocked. After waiting there for five hours, she finally returned to Goris, where she has been waiting ever since.

The corridor has since been blocked by a group of people claiming to be ‘environmental activists’, a claim that has already been refuted by the international community, since they arrived at the site accompanied by Azeri soldiers who are still there. Narine, like so many others, cannot return to her home and family, while no one can leave the enclave.

The situation in Nagorno-Karabakh itself is becoming more tragic by the day. Supermarket shelves are empty, while the Azeris have cut off the enclave’s electricity supply from Armenia leaving the region reliant on a single unit that simply cannot meet the demand. As a result, the electricity supply is constantly disrupted.

Since January 17 the gas supply was suspended as well. Hospitals are in a dire situation and the humanitarian crisis for the 120,000 ethnic Armenians is spiralling out of control, a fact confirmed by international organisations, governments and bodies, whether they have recognised Artsakh’s right to self-determination and independence, as the French National Assembly did last year, or not.

The European Court of Human Rights ruled on December 21 to oblige Azerbaijan to take all necessary and sufficient measures to ensure the movement of seriously ill people in need of medical assistance in Armenia through the Lachin corridor, as well as the safe movement of people left homeless or in need of means of subsistence, but to no avail. Last week, the local government in Stepanakert was forced to introduce a food rationing system due to food shortages.

Azerbaijan has made it clear that the Lachin corridor will reopen. According to President Ilham Aliyev, those who do not want to take Azerbaijani citizenship and give up any claims on self-determination can leave for good. For the time being, however, even this is not possible, although Armenia does not want it either. In fact, Armenia fears that opening the corridor could trigger an exodus of Artsakh’s Armenians. For now, however, the biggest problem for those who remain is simply one of survival while for those stranded outside Nagorno Karabakh it is the possibility that they may never be able to return. For Narine, there is an additional problem: her six-year-old son refuses to speak to her on the phone, thinking she has abandoned him.

Back in the “Mirhav” inn, a group of children happily agrees to speak after their teacher allows them to do so. Sixteen children had travelled to Yerevan from Nagorno-Karabakh with their teachers to take part in Junior Eurovision as a reward for their outstanding performance in artistic, sporting and other competitions. And they were left stranded in Goris for a month, away from their parents, siblings and friends. It is immediately evident that these children are gifted from the way they behave and talk to each other. But the fact that they have a maturity strange for their age is somewhat uncomfortable to see.

Asking their teacher, Aida Genjumiyan, later, her explanation sounds logical but sad: these children, like all children in Artsakh, she explains, have from a young age been fully aware of what is happening around them. They have lived through the 2020 war, the sporadic outbreaks before it too. They know where they live and what that means. Indeed, the psyche of these children can be seen in the drawings they make to pass the time, which they proudly display: flags of Artsakh, but also pictures depicting sometimes war and sometimes ideal conditions that they were not lucky enough to ever experience. The most difficult moment of the conversation is the wrong suggestion that they’ll be going back soon. They calmly reply that they don’t believe that at all from what they hear and read.

The teacher later explains that during the first few days the children were calm, but as time passed and Christmas and New Year was spent away from their families, they began to lose hope. Ayda Genjumiyan also left her family in Nagorno-Karabakh: her husband, children and two grandchildren. Her second degree in psychology, she notes, has finally come in handy. Smiling, she explains in a steady voice that she has no time to let go. Children understand everything: if she is calm, they are calm; if she is afraid, they are afraid. “There is no luxury in feeling anything else. They are my second family now,” she explains.

Typical conversations with children set the mood. OK, but isn’t it nice here? Very nice, they say, and that also makes sense, since from day one hotels and families have offered rooms free of charge to accommodate the stranded, and Yerevan has attended to their needs, sending child psychologists and other specialists to help them. All fine, but we want to go home, they say. And what will you do when you grow up? Some, already in their teens, say they will use their artistic talents: music and theatre. Others have other plans: medicine, teaching… Remarkably, none of them seems to doubt their future.

Ayda Genjumiyan writes her phone number along with the name of a Cypriot woman who studied with her in Yerevan, Vartuhin, with whom she has lost contact. Perhaps we can find her, she says. The children also say goodbye and return to their rooms, the breakfast room empties, cats climb down the windows and return to the courtyard, all in one place, where they are apparently being fed.

On the beginning of the four-hour drive back to Yerevan, military vehicles flying Russian flags drive past just outside Goris. Russia, Armenia’s traditional ally and the guarantor of the Nagorno-Karabakh agreement, has not acted to stop the Azerbaijani offensive in 2020 because both itself and the West, while repeatedly condemning Azerbaijan for its tactics to drive out the remaining Armenians, have major interests, especially in energy, with both Baku and its biggest ally, Ankara. It is through these two that Russia’s energy exports continue.

In addition Russia is now trapped in its invasion of Ukraine and can hardly afford another front. So Moscow, like the West, settles for exhortations, while the balance is overwhelmingly in favour of the Azeris and the future not only of Nagorno-Karabakh but also of parts of internationally recognised Armenian territory remain in doubt.

Baku has recently begun to lay claims on such Armenian territories in order to unite Azerbaijan with the Azerbaijani enclave of Nakhchivan and from there with Turkey. One look at the map is enough to understand that such a development would cut off Armenia’s southernmost tip and access to Iran, leaving Georgia as the Armenians’ only gateway to the world, as Ankara has closed its borders with it since 1993.

In Goris and elsewhere people fear that under the pretext of building a gas pipeline between Azerbaijan and Turkey through Armenia – over which Baku claims national sovereignty while Yerevan, refuses to accept such a claim – the whole of the Armenian south will soon find itself at war and perhaps under occupation. They even fear that they may join Artsakh’s inhabitants in a mass refugee exodus.

In a world that is once again in a state of great upheaval, the last glimpse of Goris below, before the car overtakes one of the many Iranian lorries that precede it on the narrow and winding mountain road, inevitably leads to the thought of what could happen tomorrow in this beautiful but always troubled, strategically critical part of the Caucasus today. For these people, who, like the rest of Armenians, have a remarkable knowledge of Cyprus and its recent history, the facts that once worked in their favour have been overturned. And they know it well.

Yet they hope for a miracle that will save whatever can be saved. Including the “Mirhav”, the inn, but also anything ‘pleasant’ that in this part of the world whose fate is tied to the energy crossroads now being carved out.

Click here to change your cookie preferences