As a British man struggled with the trauma of killing his sick wife, his fate was fraught with uncertainty and upheaval

With David Hunter’s court case winding down following Friday’s manslaughter verdict, many of the trials and tribulations have now come to light. Accusations of truth-twisting, lying and questions over the interests of justice have been slung from both the defence and prosecution in the case, which have cast a shadow over much of the human suffering behind this story.

Though Hunter emerged from the holding cells at Paphos criminal court with his hands raised in victory, earlier fears that he would be jailed for life if found guilty of premeditated murder were very much real.

Hunter, 76, who has slimmed down to half his size since the trial began, appeared to be in a state of shock once the verdict was read out and did not betray a tremendous amount of emotion. When the hearing came to a close, he moved to his lawyers and hugged them, as they all embraced each other.

His friends looked like a weight was lifted off their shoulders while others were repeatedly heard trying to verify: “was it manslaughter? Was it really manslaughter?”

Interestingly enough, all three judges unanimously adopted Hunter’s statements made in court, highlighting they accepted his motive that he killed his wife to end her suffering and only told her he would kill her to placate her – thus removing the element of premeditation.

Hunter’s journey until the verdict was fraught with uncertainty and upheaval, beyond the obvious trauma Hunter was inevitably trying to grapple with, particularly after his attempted suicide after he killed his wife, Janice. She had a form of blood cancer, which led to her incessant suffering and repeatedly begged Hunter to kill her to relieve her from her pain.

Though court adopted this view, it was not a given that it would.

It has since transpired that the defence and prosecution appear to have glaringly different interpretations of how the trial actually unfolded.

After almost a dozen court delays and back-and-forth’s, a plea deal that both sides had tried to negotiate for manslaughter charges in December last year failed to go through – only for Hunter to be found guilty of the very same charge nine months later. So, was it a waste of time and money?

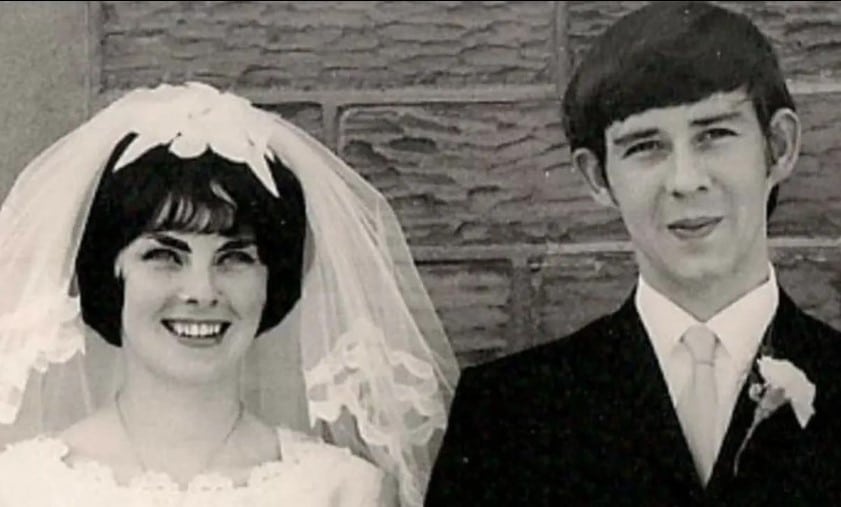

The bare facts are the Hunter killed his wife, aged 74 at the time, in their Tremithousa home on December 21, 2021.

He then tried to kill himself, a fact the court never disputed, with the judges saying that had police not intervened on time, Hunter would not have been alive, and therefore not facing trial.

Michael Polak, a lawyer on Hunter’s defence team, said the manslaughter deal failed for reasons they did not know, suggesting politics, dogma and even the attorney-general himself as part of this.

He argued the prosecution wanted the agreed facts to be Hunter pleading guilty to manslaughter but only on the basis that Janice never asked him to end her life, she was not in pain, and he did not do it out of love for her.

Polak described this as simply nonsensical.

Responding to the claim, state prosecutor Andreas Hadjikyrou did not mince his words saying Polak’s statement “has no bearing on reality” and in fact argued it was the defence’s insistence on wanting a suicide pact to be an agreed fact in the case, that eventually lead to the downfall of the deal.

But to take things in order, Polak explained to the Cyprus Mail he first tried to reach a deal on the crime of assisted suicide, writing a lengthy letter to the attorney general. This was ultimately rejected.

“The facts of the case would not allow for this charge,” Hadjikyrou said.

Assisted suicide, which comes with a penalty of up to 10 years in jail, would require someone to offer the ‘assistance’ i.e. painkillers but an individual had to carry out the killing themselves. “Someone could bring the pills but the person wanting to commit suicide would have to swallow them.”

After this went downhill, Hadjikyrou states the prosecution then countered with a plea deal on manslaughter charges.

He argues the defence “insisted” that an accepted fact in the agreement should be that Janice and David Hunter had a pact – an agreement that he would kill her and then kill himself.

Prosecution resisted this, citing lack of substantial evidence that there was in fact a pact and fear of precedent in light of this. Any person could one day kill their spouse and say they did it to end her suffering, Hadjikyrou argued.

In its court decision, the three judges made no reference to a suicide pact. They stuck to agreeing a note found after the incident was indeed Hunter’s. It read “my wife is in so much pain, she has asked me to help her. So we have done it together.”

Hadjikyrou said this note in no way pointed to an agreement – this was not mutually signed, there was no witness.

The prosecutor also refuted Polak’s statement that the agreed facts they were trying to establish included a denial of Janice’s pain and Hunter’s love for her.

“We had testimony that she was sick, we knew she went to the doctor regularly. We had testimonies from neighbours that they were a loving couple with no fights and took care of each other.”

Hadjikyrou said that if the prosecution doubted those facts and believed that Hunter had ulterior motives, and did not love her, then why would they contemplate manslaughter to begin with?

“The reason our motion for manslaughter did not go forward was their own insistence on something that no prosecutor in any country could objectively accept.”

Polak on the other hand argues “we turned up at court ready to plead on these facts twice.”

“They gave the option of Hunter pleading on the basis that Janice never asked him to end her life (which was not true) or go to trial on murder.

“A very difficult decision and one he shouldn’t have been placed in, if the prosecution was acting in the interests of the justice as they should be.”

Nonetheless, the conclusion of the case illustrated the judges accepted Hunter’s testimony in its entirety. His motive to kill her was accepted – and in fact, had not come under particular scrutiny throughout the trial.

Though Friday’s outcome led to the manslaughter verdict anyway, it was a bigger gamble because no one could predict the outcome – premeditated murder was very much on the table.

The court also accepted Hunter’s statement which highlighted that when he told Janice he would kill her, he said it only to placate her. Prosecution had argued Hunter’s earlier agreement to the killing was evidence of premeditation – but the judges ruled that he did it to appease her.

The judges also rejected the prosecutor’s view that evidence of Janice’s struggle as her husband tried to suffocate her, was an indication that she wanted to live. It was put down to an instinctive reaction, the decision reads.

An argument put forth by the prosecution that suffocation was a harsh method of killing, rather than swallowing pills was refuted by Hunter saying his wife could not swallow pills. The court did not dispute this either.

Additionally, though the court heard evidence that Janice was not in fact terminally ill, the judges accepted that both Hunter and his wife believed she was, and this had been shaped by the fact that Janice’s sister had died of leukaemia, which the couple thought Janice had.

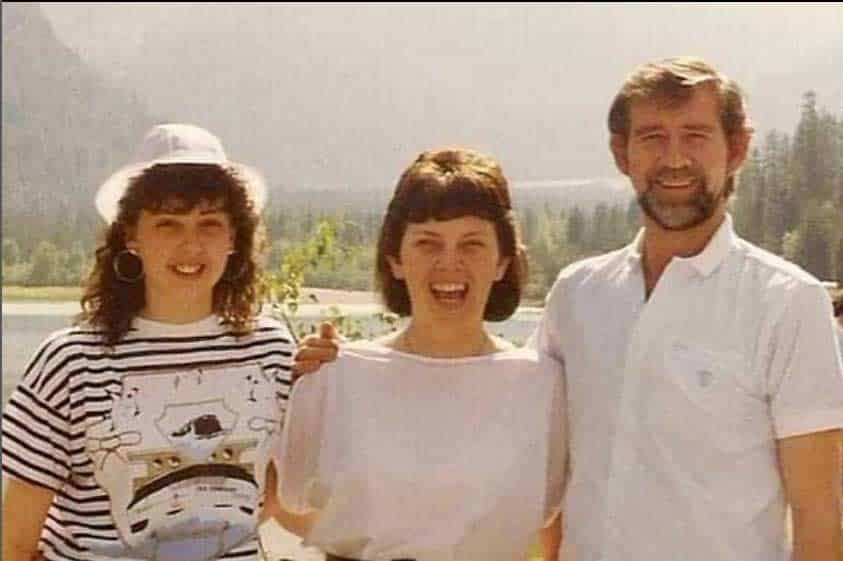

Whatever the truth is over what happened between the prosecution and defence, it has become evidently clear that much has happened behind the scenes, while Hunter has waited to hear his fate for around a year and a half. His daughter Lesley has repeatedly called for the judges to show compassion in their verdict and sentencing – with defence hoping for a suspended sentence – so her dad can go back home to the UK. “It’s what my mum would want, what I want, and what we need as a family,” she told Good Morning Britain earlier in the week.

Hunter on the other hand, has maintained from the onset that he wants to stay in Cyprus to be close to his wife, and visit her grave, which he has not yet been able to do.

After the verdict, Hadjikyrou said that although manslaughter can also come with a life sentence, “the facts of the case do not point to that direction”.

Click here to change your cookie preferences