A new film documents how antiquities department director Vassos Karageorghis’ oversaw the safekeeping of the Cyprus Museum’s artefacts in the panic of 1974

On August 16 or 17, 1974 – a couple of days after the second invasion – an announcement went out on CyBC radio: “The director of the Department of Antiquities requests those of the department’s employees who are in a position to return to work, to do so immediately.”

The director in question was Vassos Karageorghis – and the purpose of the radio message was to enlist the staff in a great, and urgent, project: to collect as many of the antiquities in the Cyprus Museum as possible, pack them in crates, and transport them to safety.

The project was carried out successfully over about three months, rescuing over 1,000 items – and is now the subject of a stylish 14-minute short film (produced by the Press and Information Office, directed by Petros Charalambous) called Operation Museum, which premiered on Friday at a special screening attended by President Christodoulides and other notables.

That said, the film takes a bit of poetic licence, having Karageorghis – played by Andreas Tselepos – coming back to Cyprus and immediately taking a taxi to CyBC headquarters in Nicosia, having first called the station from a pay phone with a desperate plea for assistance. “You are the only ones who can help, to make an announcement on my behalf.”

In fact, though Karageorghis was away during the first invasion in July, he’d been back for a while by the time of the announcement. Then again, the fact that he called in the staff so urgently – and so soon after the second invasion – suggests that the situation did seem quite dramatic.

It was a chaotic time in general, Maria Hadjinicolaou (played in the film by Dora Makriyanni) told the Cyprus Mail.

“Lies were flying around,” she recalls. People were claiming “they’d heard that [the Turks] were coming to take all of Cyprus… You could go crazy with the stuff you were hearing all day.”

When it came to the museum, it made sense to be worried; the Green Line was (and remains) just down the road.

More importantly, the museum was part – at the time – of a small, strategically important zone that also included Cyta headquarters, parliament and Nicosia general hospital. It made sense to fear that the Turks might launch one last offensive to capture this area – hence the desperate bid to remove all important antiquities before they could do so.

Having said that, it doesn’t appear that ‘Operation Museum’ was a top-down government project – if only because the government had more pressing issues, from housing thousands of refugees to trying to resuscitate the economy. It seems to have been entirely Karageorghis’ own initiative.

Hadjinicolaou – who was only a 20-year-old technical assistant at the time – doesn’t claim to know what went on behind the scenes, but recalls her boss being “very agitated” in those weeks, staying late (as was his wont) and trying to whip the troops into shape.

He must’ve liaised with the transport ministry and other departments (the crates used to ship the antiquities were made by Public Works, which also oversaw their packing and nailed them shut), but “might’ve found a bit of resistance there”, she speculates. The idea of essentially emptying the museum – it remained empty for four years, till the items were returned in 1979 – can’t have been an easy sell.

There were practical problems too, of course: where to send them, for one thing. The airport was out of action, and ships to Greece were already overloaded.

Some of the antiquities did go to Greece, and were later exhibited at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Most of them, however, went to the British bases, where they remained in their crates for safekeeping.

Interestingly, Hadjinicolaou recalls that she happened to overhear her boss talking about this – telling the Curator of Antiquities that he’d received assurances from the bases commander – which was how she found out about it.

Not only was the destination being kept secret, in other words (which made sense, not to mention that it might’ve been politically awkward), but it seems that arrangements hadn’t even been finalised when the packing began – another indication of how urgent Karageorghis considered it.

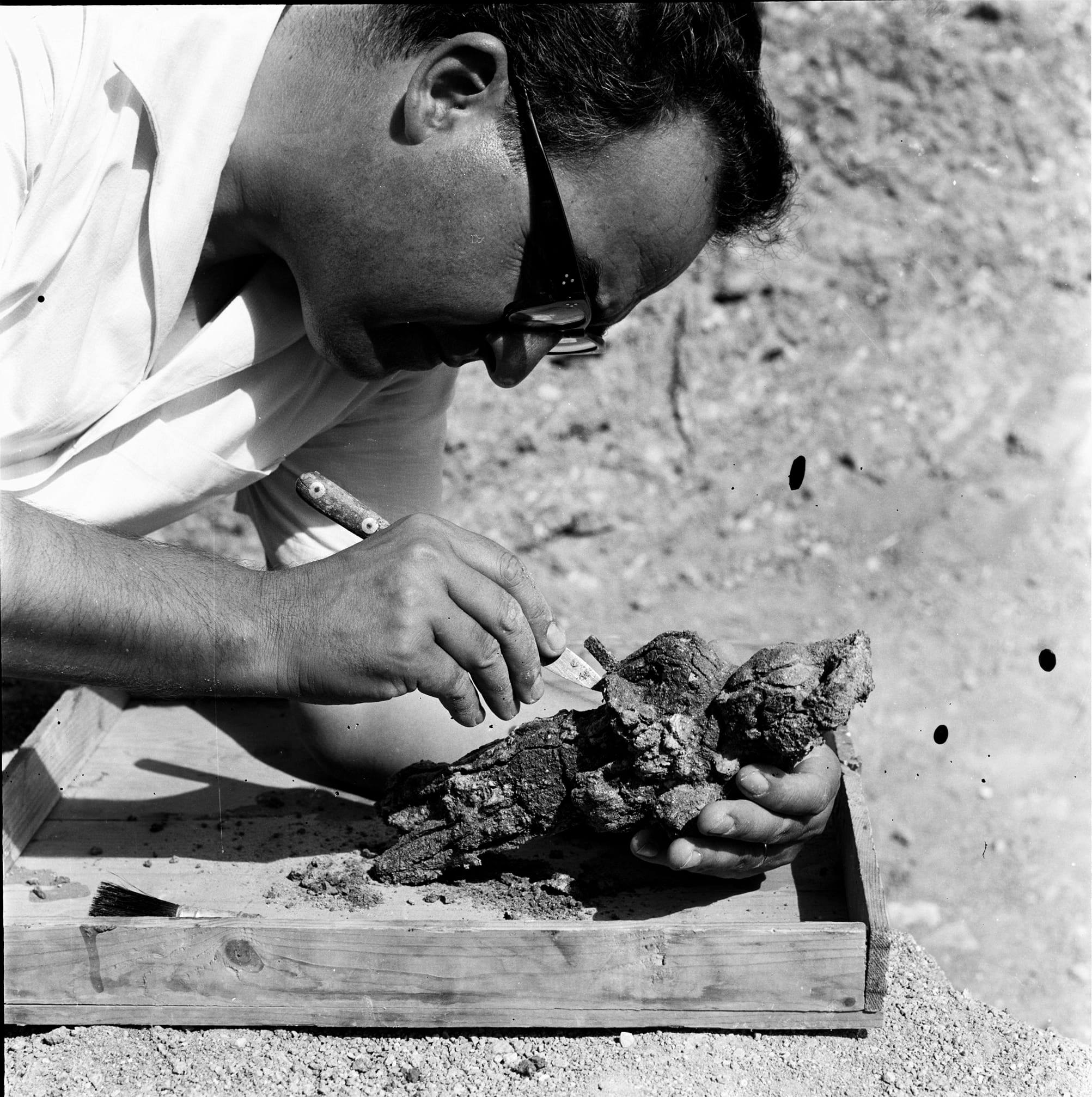

There was no bubble-wrap in those days. The antiquities were packed in large quantities of old newspapers, brought in from news agencies, and even larger quantities of straw: “Trucks were coming in and unloading it”.

Meanwhile, staff were making lists and updating the register. Every item had an inventory number, “even its position in the display case had been noted down”.

It took two people to remove each exhibit carefully, two more to do the packing. For weeks, she jokes, anyone passing by outside the museum would’ve thought it was a carpenter’s shop, so relentless was the din of nails being hammered.

In the end, Operation Museum was perhaps not so vital in itself. After all – as we now know with hindsight – there was no immediate danger to the ancient treasures.

Yet it’s fascinating in two ways. First, as a vivid memory of 1974 – and second, as a testament to Karageorghis himself.

In the film, Tselepos plays him in a very particular manner: well-spoken, distant, fastidious – the usual movie shorthand for ‘obsessive genius’.

“He was strict. Very strict,” says Hadjinicolaou. “When I first arrived, I was scared of him!” Karageorghis wasn’t the type to joke around, or be a buddy to his employees. He expected people to work hard, and could be very fierce if they didn’t.

Karageorghis, who died in 2021 aged 92, devoted his life to archaeology. “He published constantly, constantly,” recalls Hadjinicolaou – who worked with him for 45 years, 16 as director then three decades after he’d retired but was still in touch with the department. “For that man to feel alive, he had to have work to do.”

That said, he mellowed with age – and of course his early ‘strictness’ was exactly what Operation Museum demanded.

Look again at that radio announcement: a time capsule in itself, for several reasons.

For one thing, we may wonder why Karageorghis had to ask CyBC to pass on a message to his staff, instead of just calling them – but “we didn’t have phones, like they have now,” explains Hadjinicolaou. She herself, living in Lakatamia, didn’t get a landline (never mind mobile phones!) till 1976.

For another, note the phrasing: those employees “who are in a position to return to work…” That, too, is a sign of the times – because the department was depleted, in those post-invasion days.

Some had kids and nowhere to leave them, infrastructure having collapsed. Some were too depressed to return to the office. Some had fought in the war, and been taken prisoner on the other side – or never come back at all.

Finally, note the date: August 16, but it may have been the 17th – because our source is Maria Hadjinicolaou, and details are beginning to grow fuzzy as time marches on since the invasion.

“I didn’t think I’d have to remember all this stuff 50 years later,” she explains sadly.

Operation Museum will go on wider release soon

Click here to change your cookie preferences