Will the government cross the Rubicon, take the plunge – pick your idiom – this coming Tuesday when all the players sit down in Nicosia for a powwow on the Great Sea Interconnector? Perhaps. But whatever happens, it does appear that decision time looms and that the Cypriot side is under a great deal of pressure to give the green light.

Two main issues: first, the Cypriot side may not have done its prep work on time and thus left it to the last moment when the walls began closing in. But you could also read it another way: that Greece’s Independent Power Transmission Operator (Admie), the project promoter, is being excessively pushy, with some likening their behaviour to overt blackmail. Admie has warned that unless a deal is clinched very soon, it cannot make payments to Nexans, the manufacturers of the subsea cable. And if that occurs, it’s basically game over.

Secondly, the unknowns over the project. And there are many. Despite being briefed by the government, members of parliament are complaining about the lack of transparency on key aspects of the mooted interconnector project that would link Cyprus to Crete and end the former’s energy isolation.

For this report, we tried contacting a number of officials on Friday, but could not reach them. Energy Minister George Papanastasiou was at the time in a meeting with the finance minister – presumably brainstorming ahead of Tuesday’s crunch meeting of the stakeholders. And neither the finance ministry’s permanent secretary nor the head of the energy regulatory authority (Cera) returned our calls.

The Cyprus Mail managed to speak to people on the periphery. Both agree the entire endeavour is fraught with uncertainties which ought to have been resolved long ago.

Charalambos Theopemptou, an MP with the Greens and an ex-Environment Commissioner, tells us that the whole affairs smacks of an unscientific approach, which he finds astounding.

“There should be a text, a document, out there that we could reference, with numbers and calculations about the interconnector. I have not seen any such document, nor am I aware any such exists,” he commented.

“It beggars belief,” he went on. “This is after all an engineering project, so having the basic engineering parameters should be standard procedure. But we don’t have them.”

For example, said Theopemptou, we – meaning the public at large – don’t know who would operate the cable. Would it be the Electricity Authority of Cyprus, or some other entity? And if the EAC, would they need to set up an affiliate/subsidiary?

“Also, who will charge for the electricity from the interconnector? In other words, who will have the financial management? Again, unclear.

“In short, where is the science behind it? Instead we’ve got rumours, speculation, commentary – but no scientific study as a baseline.”

Elaborating, the MP walks us through what should already be in place before even embarking on a project of such magnitude. The Great Sea Interconnector is said to cost €1.9 billion – at the moment.

“A country”, he asserts, “should have an energy policy that’s written down, we have no such thing. The EU asked us to do this long ago, we didn’t.

The number one constituent of an energy policy should be a reduction in demand. That’s step one, says Theopemptou.

“Step two, promote renewables. Now let’s go to step three. Let’s say you haven’t done anything to reduce demand – for example you didn’t invest in buildings with better energy insulation. OK and let’s say you haven’t increased usage of renewables either, so you’re still relying on fossil fuels, meaning you haven’t shrunk your footprint of greenhouse gas emissions.

“Assume all that. So, what next? Well, you’d need to at least ensure energy security. That means that if something happens to your energy infrastructure – like an accident, a natural disaster – what alternatives do you have? What happens, say, if the Vasiliko power station goes offline?”

That’s precisely why the EU promotes interconnectivity, says the MP – to ensure energy security.

“OK so what if Vasiliko is damaged, like in 2011? Essentially, we have no electricity. What might our options be then? We could for instance build another, smaller power plant, let’s say in Paphos. That would be one option to attain some level of energy security.”

At the end of the day, you need engineers to sit down and figure out the best solution.

“But here, with the interconnector, we’re told that it will ensure energy security, and we should just take it on faith. But is it even true? We need to verify that first, and it seems we haven’t.”

Theopemptou poses another question which he says hasn’t been answered: if the interconnector offers cheaper electricity, wouldn’t everyone just switch to that? Why would any consumer stay with the EAC? And wouldn’t that spell the end of the state power utility?

Here it gets a little weird. Recently EAC management said it would support any solution that drives down the price of electricity for Cypriots. The statement stands out because that could potentially mean curtains for the EAC itself.

Theopemptou compares this ‘weird’ statement by management to the pervasive sentiment among the EAC workers.

“EAC trade unions, whom I spoke with a few months ago, are dead-set against the interconnector – they fear it will mean the end of the EAC. And if the EAC does shutter, we would have a real energy security issue. Then we’d be left with just the interconnector – all our eggs in one basket.”

There’s also of course the daunting cost of the interconnector – almost €2 billion.

Theopemptou puts it this way: “Why does it cost that much? Well for me it’s obvious – because of the daunting technical challenges.”

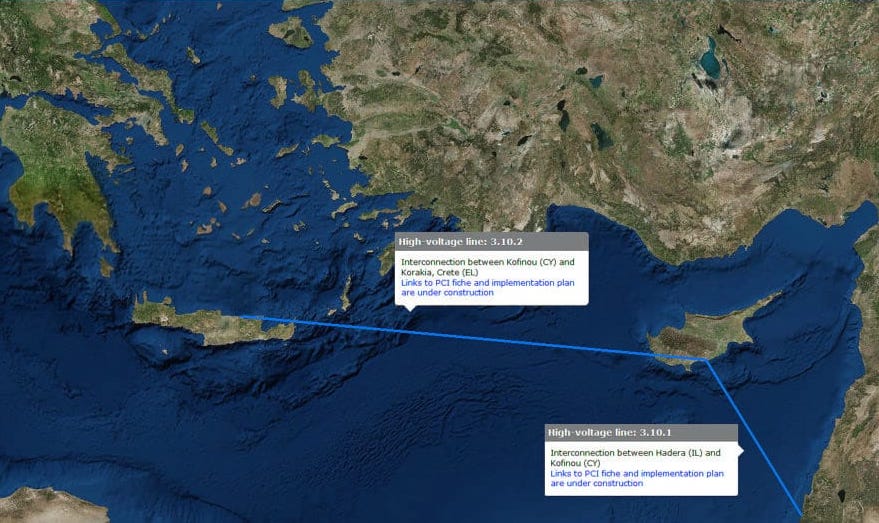

And it doesn’t end there. During a parliamentary discussion on July 30, none other than the energy minister cited two uncertainties that could alter the project’s price tag. The first uncertainty is the lack of a signed contract between Admie and Siemens, the company pre-selected to build the converter stations in Kofinou and a location in Crete. The other uncertainty relates to the final selection of the subsea cable’s route.

According to reports, the seabed survey in the area where Nexans will lay the cable, as well as Admie’s negotiations with Siemens for the converter stations, will not conclude until September 2025. These technical aspects could either dramatically inflate costs – which consumers will ultimately bear – or else the project may never be completed.

Meantime Admie is turning the screws. Daily Phileleftheros, for example, has been carrying half-page long advertorials, sponsored by Admie, extolling the virtues of the interconnector.

Another source, who requested anonymity, stresses that it was agreed long ago that the interconnector project would go ahead only if deemed technically feasible and financially viable.

“This was agreed upon years ago, but it appears we’ve not made it far past square one,” the industry source told us.

The same source recalled how in October 2022, and amid much fanfare, then-president Nicos Anastasiades inaugurated the EuroAsia Interconnector – as it was then known – declaring that construction was beginning.

“Right now”, our source said, “we still don’t know key parameters. To give an example: is there a cap on how much electricity Cyprus will take in from the interconnector? Is it 20 per cent, 30 per cent of our capacity, what?

“Matters like these should already have been sorted out when the 2022 inaugurals took place.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences