The irony of the overthrow of the Syrian dictator Bashar Assad last Sunday is that he fled to Russia as a refugee after he turned his people into refugees and changed the political landscape in Europe in the process.

The uprising against his rule began in 2011 at the tail-end of the Arab uprisings that began in 2010 when Arab dictatorships, including Syria’s, came under sustained popular pressure to democratise their regimes. The uprisings in Egypt and Libya got rid of strong men Hosni Mubarak and Muammar Gaddafi but not Assad who was not a strong leader but whose regime was as cruel as it was tenacious.

In Syria the uprising deteriorated into a civil war and caused many Syrians to seek temporary refuge in neighbouring Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. As often happens the refugees initially hoped to return but in 2015 Russia intervened militarily and helped Assad put down the insurgency. Around that time thousands of Syrian refugees began to head for Europe in search of permanent refuge in such large numbers it caused panic in European capitals. It forced the German leader Angela Merkel to take in almost a million Syrians at great political cost long term because it turned a significant segment of the population in Germany and Europe against refugees and immigrants.

In the end the refugee crisis in Europe resulted in a fundamental change in the post-World War II consensus politics to a much more polarised nationalist politics reminiscent of the inter-war years. The rise of the populist right in most European countries is not as bad as the rise of the Nazis and Fascists, but the opportunity the huge influx of Syrian refugees in 2015-16 gave to populist politicians to exploit the otherness of refugees, has turned the alternative right into an electoral force with a number of important electoral successes across many countries in Europe.

Marine Le Pen in France, Georgia Meloni in Italy, Viktor Orban in Hungary, Nigel Farage in UK and Geert Wilders in the Netherlands owe their success in whole or in part to the influx of refugees and the resentment their arrival caused across Europe.

Refugees are welcome when they are geniuses like Albert Einstein and Pablo Picasso, the poet Pablo Neruda, the writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the ballet dancer Rudolph Nureyev, the father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud, and the odd royal like the late King Constantine of Greece – to name a few randomly. But when refugees arrive in their thousands from places like Syria they are perceived as demanding compassion and are unwelcome and often even perceived as posing a security risk.

It was therefore not surprising that Germany, Britain, France and other European countries immediately suspended decisions in refugee cases from Syria the moment the Assad regime fell last Sunday. It was legally justified as most Syrian refugees feared persecution from the Assad regime that was no more, but the suspension of decisions was done with indecent haste given the new regime needs time to prove its democratic and human rights credentials before being expected to take back its citizens.

What is going to happen is that those whose applications have not been determined will be told they are now reasonably be expected to return, assuming the situation in Syria does not descend into a chaotic civil war.

Those who have already been granted refugee status are governed by the cessation clauses of the 1951 Refugee Convention. Other things being equal, most European countries would not remove recognised settled refugees unless they voluntarily return to Syria permanently. Or the change of circumstances following the overthrow of Assad mean they can no longer refuse to return if required to do so – on deportation for example.

The change of regime does not necessarily mean that there will be no more refugees from Syria. Supporters of the old regime will probably flee and some will end up in Europe – as the BBC’s Jeremy Bowen reported last week a few are already filtering into Lebanon. They would be entitled to refugee protection unless excluded by the Refugee Convention’s exclusion clauses that denies refugee protection to those who have been guilty of war crimes and grave breaches of international humanitarian law or crimes against peace.

Those guilty of such grave crimes would be entitled to the protection of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) under which they would not be returned to Syria if they are likely to be executed or suffer torture inhuman and degrading treatment. That does not mean they would escape prosecution because their crimes are international crimes for which there is a universal jurisdiction to prosecute and punish them in most European countries.

The hope is that the new regime will be all inclusive and few Syrians will be forced flee as refugees. Perhaps that is wishful thinking because history suggests that what usually happens is that the new regime is feared by the supporters of the old in the same way its own supporters feared the overthrown regime.

This is what happened when the Shah of Iran was overthrown in 1979. I remember that as a young advocate prior to 1979, I was representing refugees from Iran who fled from the Shah’s secret police – the dreaded security police Savak.

After the Islamic Republic of Iran took power, I was representing refugees in fear of persecution of the revolutionary guard of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Some were not even supporters of the Shah; just middle class Iranians in fear of the fundamentalist nature of the regime.

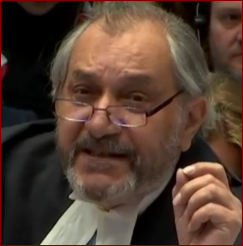

Alper Ali Riza is a king’s counsel in the UK and a retired part time judge

Click here to change your cookie preferences