‘The work was superb – almost unprecedented for its time. But it was also cartography in the service of empire’

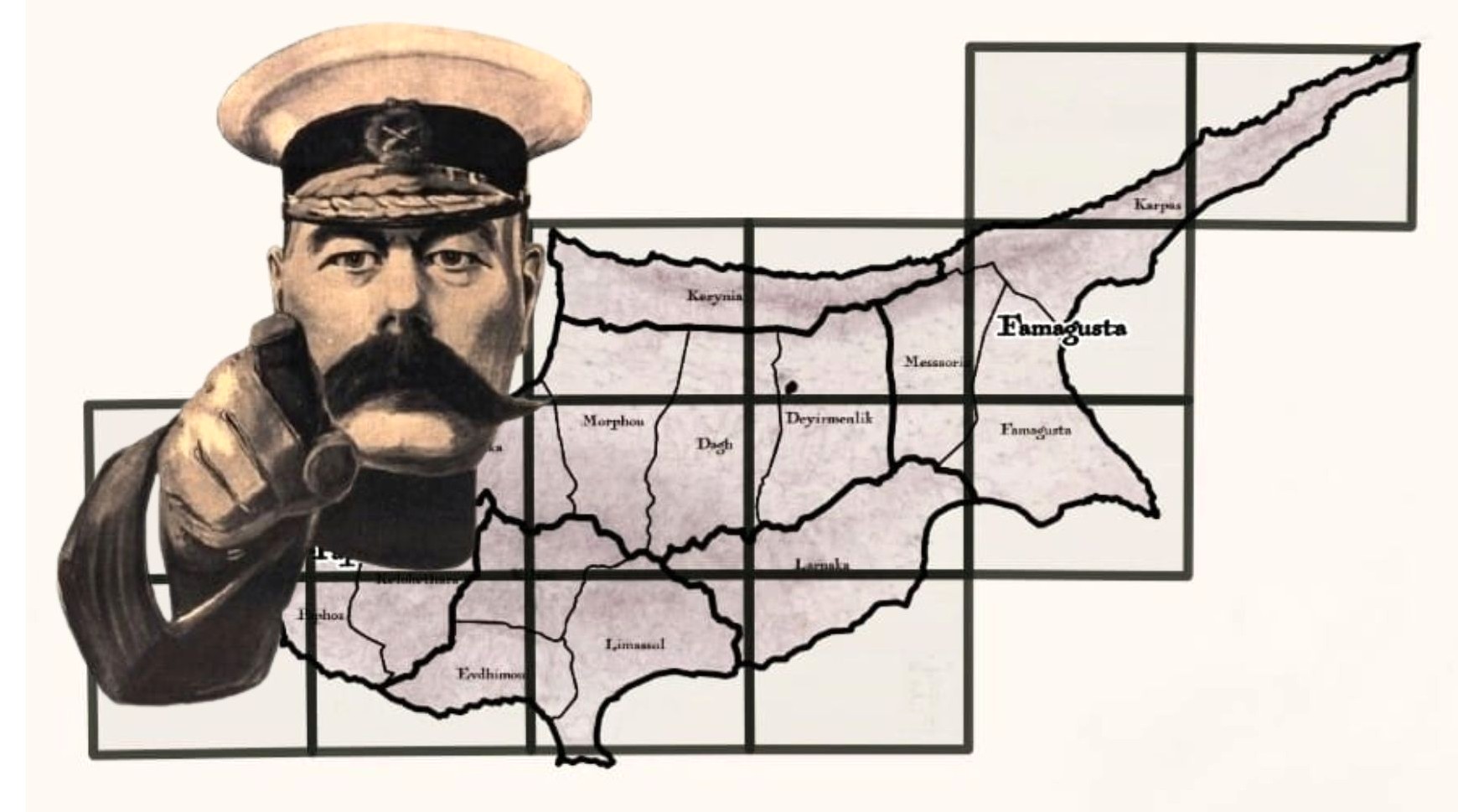

This isn’t just a map of Cyprus. It’s THE map!

The map that, for over 100 years, defined how our island was seen, measured and governed. The map that laid out not just borders and boundaries, but distinct lines of power that – even today – echo through our land, our identity, our past.

For the late 1800s, it’s an astonishing piece of work: every village, valley and ridge recorded in meticulous detail – everything from crumbling chapels to forgotten footpaths clear and sharp. Metres in length, it’s divided into 15 separate sheets – which, put together, show the entire island of the time. And, in its totality, it captures Cyprus as it was seen through British eyes – precise, ordered and ready to be ruled.

Because this map wasn’t just a record. It was a reframing…

The year was 1878. The British had just assumed control of Cyprus from the Ottomans as part of a secret agreement. Officially, it was a ‘protectorate’. In practice, it was something far more strategic– a foothold in the Eastern Mediterranean, ripe for reorganisation.

But first, the colonial power needed to understand the island, understand what they now ‘possessed’. And for that, they needed a map. Not a sketch or a general impression; not a ‘here be dragons’ sketch or a vague terra incognita plan. No. What was required was a detailed, scientific survey that could lay the foundations for governance, taxation and control…

So they dispatched a young officer with a reputation for precision and intelligence: Horatio Herbert Kitchener – just 28 years old, but already marked out for greater things. Not only a skilled cartographer, but highly educated, ambitious, and a lover of both order and detail. A complex man for a complex task.

Over the course of several years, Kitchener travelled the length and breadth of the island, conducting a full triangulation survey; one of the first of its kind in the region. Working with a small team of Royal Engineers, he surveyed every corner of Cyprus with scientific precision: hills, streams, villages, roads; ancient ruins and current sites of interest; land cover and administrative borders.

In Nicosia and Limassol (both of which warranted more detailed city plans, reflecting their growing administrative and commercial importance under British rule), even the palm trees are marked – possibly as vantage points or visible reference in an otherwise flat urban landscape.

The work was superb – almost unprecedented for its time. But it was also cartography in the service of empire.

When complete, Kitchener’s map changed how Cyprus was seen – not just by the British, but eventually by the world. And yet, it also brought lasting benefits: supporting early efforts in infrastructure and administrative planning; laying the foundation for the island’s Land Registry Department – a process that might otherwise have taken decades.

“This was the first map under the British administration: a vital snapshot of 19th-century Cyprus,” says Dr Christos Chalkias.

“It contains an extraordinary amount of detail – settlements, religious sites, land use, physical features – many of which can still be seen today. So it’s not just a map, it’s a historical record of the island at a pivotal moment of in history.”

Professor of Geography and Vice-Rector of Research, Development and Lifelong Education at Athens’ Harokopio University, Chalkias headed the team behind the map’s recent digitisation.

Working with one of the few surviving original copies of Kitchener’s map, lent to the university by the Sylvia Ioannou Foundation (a non-profit dedicated to collecting, conserving, and promoting Cyprus’ cultural and historical heritage) the project was almost as massive as the map itself!

Over the months, the team meticulously digitised all 15 sheets. And then, they took things one step further: combining historical cartography with modern geospatial technology to layer on current geographic data.

The result is a fully interactive version of Kitchener’s original map. A detailed, user-friendly web application that allows anyone to explore Cyprus as it appeared in the 1880s – zooming in on villages, tracing long-vanished paths, and comparing the past with the present in real time.

For us, the public, this is far more than just a historical resource. It’s an evolving tool, layered and alive, waiting to be explored.

We can toggle between the 19th century map and a modern satellite view, flipping back and forth to see just how much the island has changed. We can inspect everything from administrative boundaries to village borders, place names to palm trees, roads to rivers, wells to cemeteries. And, most importantly, we can learn about our past – and present – as we digitally layer information upon information…

The road network shows colonial ambitions for connectivity. The telegraph lines whisper stories of communication, control and empire. The hydrographic network (possibly exaggerated, Christos notes) hints at how the island was marketed: fertile, manageable, worthy of foreign investment.

What we choose to switch on – or off – changes what we see. And what we see shapes how we understand our past.

Because while the Kitchener map was born of empire, today it offers us something far more personal: a chance to trace the past, to see the island through the lens of time, and to understand how place and identity have shifted.

For historians, researchers and archaeologists, it offers an unmatched visual record of Cyprus before modern development – before roads widened, fields disappeared and cities sprawled. But for many Cypriots – especially those in the diaspora – this digitisation allows us to locate long-lost villages; to find ancestral names; to walk, virtually, through the landscapes our great-great-grandparents once called home.

In a country where oral history often fades faster than the land it describes, Kitchener’s map of Cyprus becomes a bridge that connects memory to place. And it begs us to ask the deeper questions: Why here? Why then? Why us?

Because to understand who we are – or were – we need to start with a map. And this is THE map.

To interact with the map, visit shorturl.at/nHlBl or gaia.hua.gr/kitchener/

Click here to change your cookie preferences