Finding a dead body as well as the next guy

Speaking in 1895, Oscar Wilde responded to a critic questioning the fact that all his characters tend to sound like him, with the assertion that such criticism could only exist because of critics’ lack of exposure to works written by ‘anyone who has a mastery of style’, and that ‘the work of art, to be a work of art, must be dominated by the artist’. If this seems like too diffuse a way to begin a review of a piece of detective fiction published in 2024, I apologise. But I can explain.

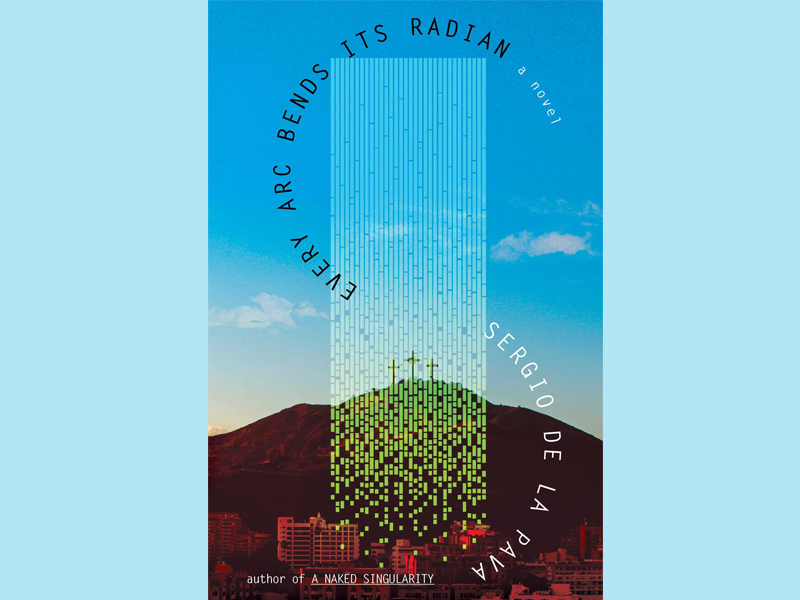

The most remarkable thing about Every Arc Bends Its Radian is that everyone we meet, whether detective, henchman, super-villain, or plastic surgeon’s assistant, speaks in an idiolect that is, in lexis and syntax, a compelling blend of the literary, the philosophical, and the clipped elision of a busy New Yorker trying to get their point across. Why is this remarkable? Because for most writers, making all their characters speak in a manner that is both near-identical and logically divorced from character itself would be a catastrophic weakness. For de la Pava, it’s a strength. There’s only one explanation: mastery of style.

And, while I haven’t read enough of his work to say this is the domination of art by artist, Every Arc Bends Its Radian is utterly dominated, like all the best detective fiction, by the voice of its first-person protagonist: Riv del Rio. His is the character that makes the idiolect sing most and find its perfect resonance, since by his own admission, ‘I guess I’m like a poet/philosopher/private eye?’ As such, when requested to locate a rich woman’s missing MIT-grad-student daughter – del Rio having fled New York for Cali in the wake of an initially obscure personal upheaval – decides, ‘I can probably find a dead body as well as the next guy.’

Of course, the body’s not dead. And that’s not the only way in which the object of Riv’s search – Angelica Alfa-Ochoa – defies expectation and categorisation. To get to the bottom of all that (and more; you’ll get my bad pun when you read the book), Riv has to go through the enigmatic and terrifying Exeter Mondragon, underworld boss, connoisseur of human misery and expiration and self-professed killer of God.

Doing so takes del Rio and the reader on a journey that spans the mythological, the scientific, the philosophical and the speculative, all the while delivering the surveillance, deceptions and deductive brilliances that typify good detective fiction. Perhaps inevitably in a book that does so much so well, it struggles to come to an ending that does justice to all that went before. But what goes before is just so, so good.

Click here to change your cookie preferences