Outback noir gets a taste of Greece

By Philippa Tracy

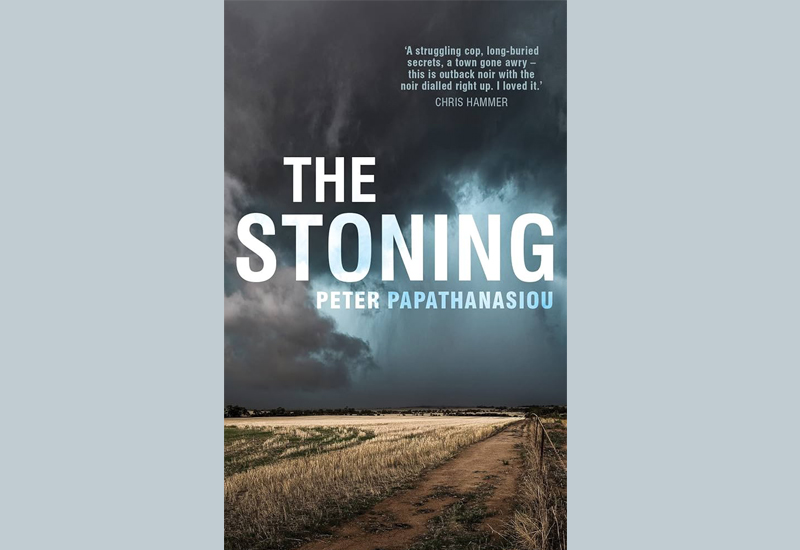

There is something very atmospherically appealing about a crime novel set in the Australian outback. Jane Harper’s debut novel The Dry inspired a whole new sub-genre of crime fiction back in 2016: outback noir. I loved that novel, as well as her second one, Force of Nature. So, naturally when a new outback noir, debut crime novel caught my eye, I had to read it. This one is written by a Greek Australian Peter Papathanasiou, and features Detective Sergeant Giorgios Manolis, the son of Greek immigrants.

It starts with a shockingly violent crime, the stoning of a young woman on the outskirts of a rural outback town. The scene is set. You can feel the intensity of the heat, with kangaroos “skipping across the hot asphalt,” trying to get some relief from the “dry, yellow plains.” DS Manolis returns to his fictional home town of Cobb, where his parents used to run a Greek café that welcomed everyone, “espousing the Greek virtue of filoxenia – “ generosity of spirit”. It is supposedly a close-knit community still but tensions are running high between the white population, the indigenous Australians and refugees at the immigration detention centre.

Papathanasiou hopes that the book is “more than a simple whodunit.” He has taken a risk including what he calls “many hot-button issues.” It is clear that race and migration are important themes in the book when one of the key characters tells Manolis that “multiculturalism is the greatest failed experiment.” He also explores what another key character, Constable Andrew ‘Sparrow’ Smith, describes as, “our gross neglect of Aboriginal people”. Papathanasiou says he spent a lot of time researching and consulting on his First Nations character, Sparrow, who has a clear and strong voice in the novel: “Why is it you reckon all whitefellas think they’re under siege?”

Some locals feel that the detention centre, known locally as, “the brown house”, has been “foisted” upon them. Sparrow talks about the historic tensions between the blacks and whites who were once “two communities with a common home.” He says the detention centre “changed all that.” The book can seem a little didactic at times, with reflections on the shame of White Australians, the nature of detention centres as prisons and “our obligations to vulnerable people fleeing persecution.” These are not easy issues to explore in fiction. There are also some amusing asides about the Greek community, his parents and the nature of marriage. “Manolis remained firmly of the view that Greek women were the strongest on the planet because they’d endured a lifetime of Greek men.”

While Papathansiou has integrated some serious and important themes into this novel, it also works well as a good old-fashioned page turner of a whodunit. Like many detectives, Manolis has his own demons; his relationship with his parents wasn’t easy and his marriage isn’t great. He has recently separated from his wife and misses his young son. He naturally admits to Sparrow: “I don’t always live by the book.” Cobb seems to be a place where nobody lives by the book. It is a “tiny flyspeck of a town” where, like all small towns, people gossip and word spreads “like an infection” and according to the one female detective in the town, women are treated “like animals.” It is a place “without optimism”. But the book is worth a read if you enjoy a good crime novel.

Click here to change your cookie preferences