A message of hope in human resilience

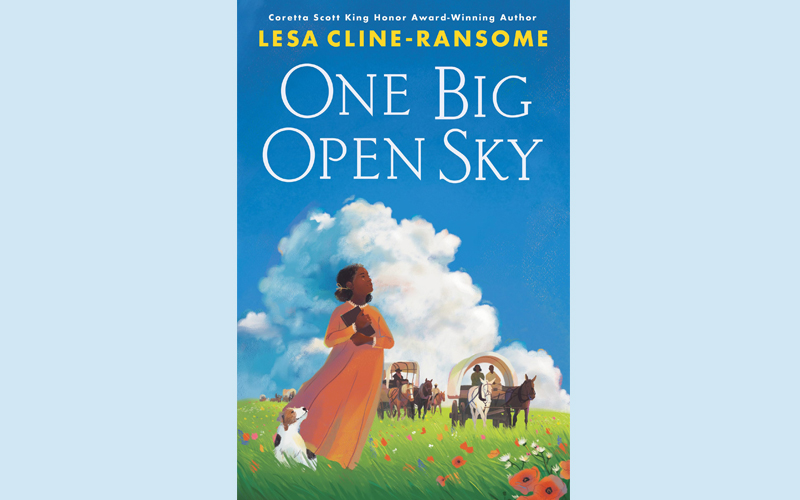

Lesa Cline-Ransome’s moving novel in verse One Big Open Sky is riven by questions of freedom. Early on in the tale of 10 black families heading West out of Mississippi to take advantage of the land promised by the Homestead Act of 1862, 11-year-old Lettie, the novel’s most prominent voice, relates, ‘Us colored folks/ ain’t never gonna be free/ the way white folks is/ We gotta find/ our own kind of free/ Daddy told me’. Later, in the author’s historical note, Cline-Ransome writes, ‘the question for me remains: Where do Black people go in this country as they seek out the freedoms that should be afforded all of its citizens’. Since the author feels the need to ask this question 145 years after the novel is set in 1879, it goes without saying that One Big Open Sky does not find an answer. What it offers, though, is a tender and compelling presentation of how the best of human resilience, solidarity, optimism and community can be formed and found in extreme and unconventional ways, and in this there is a message of hope that echoes well beyond the novel’s close.

As the Grier family make their way from Mississippi to Nebraska over the course of nine months in 1879, we experience the fear and pain and struggle and catastrophe and revelation and joy of such a mammoth expedition from the points of view of three women: Lettie; her pregnant mother, Sylvia; and Philomena, a young woman on her way to carve out the independent life she dreams of as a schoolteacher out West. One of the ways in which Cline-Ransome makes this novel richer than its basic premise is by playing out her central question in light of a world in which women have no voice, and where the answer to any question about the lack of female authority and public independence is, ‘That’s why women/ Have husbands’. The irony of just how profound, insightful and powerful the female voices telling this story are is exacerbated by the fact that the three central women all find themselves without husbands at times in the book, and it is in this that so much of their power emerges to the reader. Equally, as we move from a focus on Sylvia’s marriage to Thomas, whose easily wounded masculine pride causes problems from the outset, to Philomena’s much more progressive romance with one of their fellow Homesteaders, we are given a sense of at least one space in which a kind of freedom more than was usually afforded to black women could be found.

I haven’t told you much about the plot because, while masterfully depicted and maintained, it is subordinate to the true wonder of this novel, which comes from the relationships within it and between its leading voices and the reader. That’s what you will carry away after you close the book, which is to say that if you haven’t read it, you should.

Click here to change your cookie preferences