Through the eyes of a diplomat

By Euripides Evriviades

Ever since childhood, my imagination was seared by the exploits of Alexander the Great. Like many, I was introduced to them through lessons in classical history. The stories of the young Macedonian who tamed Bucephalus, crossed continents, and never lost a battle filled my mind with awe!

But with time, and after 43 years in diplomacy, I began to view Alexander through a different lens. Not just as a conqueror, but as a case study in diplomacy. Was he simply a military genius? Was he ruthless and expansionist? Was he an imperialist before the term existed? Or was he also something else: a proto-diplomat?

This article reflects on whether Alexander’s approach to power and rule offers relevant lessons for modern diplomacy. We must, of course, judge him within the context of his era. At its core, diplomacy involves navigating power relationships, cultural dynamics, and strategic interaction across divides. It means shaping perceptions, negotiating legitimacy, and exercising authority. And in that sense, the connecting threads are unmistakable.

What makes Alexander the great “proto”?

What was “proto” about him? Why regard Alexander the Great as the first to practise diplomacy in action? The prefix proto (from the Greek πρώτος) means “first” or “precursor.” And while the word “diplomacy” did not exist in his time, the practice – negotiating legitimacy, influence, and power across cultural and political boundaries – did. Unlike earlier rulers who governed through tradition or divine ordinance alone, Alexander actively reshaped legitimacy through strategy, synthesis, and symbolism. In doing so, he marked a distinct shift in the practice of imperial governance.

He combined cultural adaptation, strategic alliances, and perception management at a level of sophistication unprecedented in antiquity. He employed tools we now associate with diplomacy: negotiated authority, legitimacy-building, narrative control, symbolic gesture, strategic vision, and leadership, centuries before such practices were formally articulated.

Much of this was likely shaped by his education. His tutor was none other than Aristotle, who taught him ethics, logic, politics, natural science, and – perhaps most importantly – the value of human understanding. From Aristotle, Alexander likely absorbed the foundational idea that leadership demands knowledge of others’ customs, values, and reasoning. As Alexander himself is believed to have said: “To my father I owe my life, but to my teacher I owe the life worth living” (Τῷ μὲν πατρὶ τὸ ζῆν, τῷ δὲ διδασκάλῳ τὸ εὖ ζῆν ὀφείλω).

Soft power before its time

In today’s age of soft power, strategic communication, and contested legitimacy, Alexander’s methods – whether conscious or instinctive – deserve renewed attention. My professor, Joseph Nye of blessed memory, who coined the term “soft power”, might well have approved of this inquiry.

The term “diplomacy” – from the Greek diplōma (δίπλωμα), meaning a folded document conferring privileges or credentials – did not exist in Alexander’s time. Yet in essence, his actions align with the modern practice: forging strategic alliances, integrating local elites, projecting symbolic power, legitimising rule across cultures and borders, and shaping both the information and the narrative that surrounded his reign and legacy.

His campaigns offer not only a study in conquest, but also an early model of leadership, statesmanship, and pragmatic governance. As classical historian Arrian observed: “He excelled not only in conquering, but in governing.”

Alexander’s campaigns were not only military but also symbolic. After defeating Darius III at Gaugamela in 331 BCE – and following Darius’ death in 330 BCE – Alexander adopted Persian royal dress and court ritual. He performed proskynesis (προσκύνησης), a Persian act of obeisance, which shocked his Macedonian officers but signalled continuity to his new subjects.

He married Roxana of Bactria and later Statira and Parysatis, daughters of Persian royalty. These were strategic unions. At the Susa weddings in 324 BCE, Alexander orchestrated the mass marriage of 10,000 Macedonian soldiers to Persian women – a calculated attempt to fuse the conqueror with the conquered. The use of marriage as statecraft would echo for centuries, from European royal houses to Ottoman court diplomacy, as a means of forging alliances, consolidating legitimacy, and managing imperial diversity.

Arrian noted that these efforts aimed to unify the peoples of Alexander’s empire. Critics then and now have seen them as theatrical. Yet the use of symbolism to shape legitimacy remains a diplomatic tool to this day, expressed through state visits, public rituals, and ceremonial gestures.

Religious diplomacy and cultural fusion

Alexander understood the limits of occupation. He retained many Achaemenid satraps and allowed cities to preserve their traditions, so long as loyalty and tribute were secured. In Egypt, he sought divine legitimacy by visiting the oracle of Ammon-Zeus at Siwa, where he was proclaimed son of the god. The gesture may have reflected personal vanity – or even megalomania – but it was also religious diplomacy.

He established more than 20 cities named Alexandria, many of which became administrative, commercial, and cultural centres. These were not merely strategic outposts; they were instruments of Hellenistic integration. Some, like Alexandria in Egypt, evolved into vibrant hubs of learning, philosophy, and the arts, laying the groundwork for a new cosmopolitan era. In today’s terms, this was an early form of cultural diplomacy – using education, exchange, and ideas to shape influence across borders.

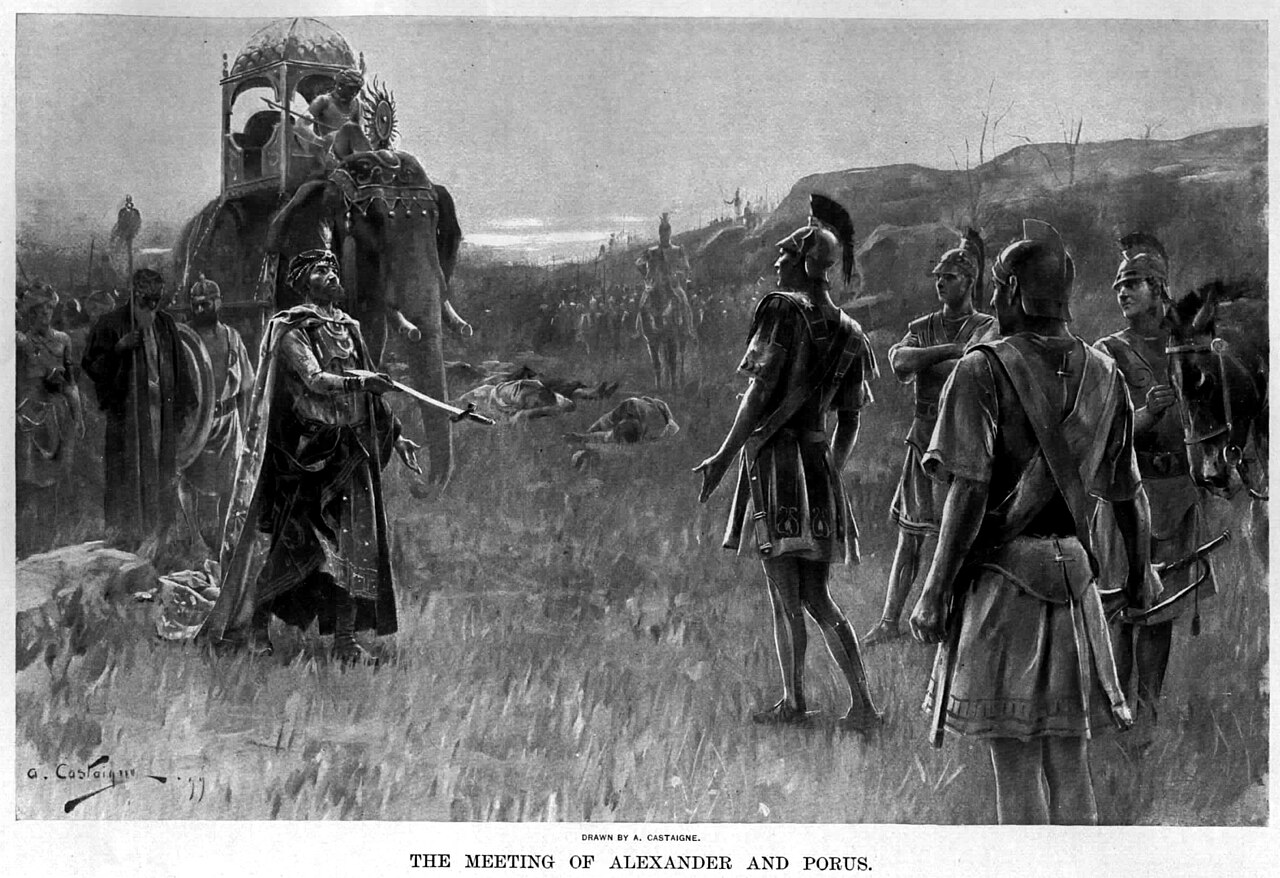

After the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BCE, Alexander defeated King Porus. When asked how he wished to be treated, Porus reportedly replied, “Like a king”. Alexander restored his territory and ruled through him. Arrian and Curtius Rufus describe the episode as one of honour and respect – an early recognition that local legitimacy often trumps direct control. In modern terms, this was delegated authority – a concept still relevant in peace processes and transitional governance today.

Failures in diplomacy and statecraft

Alexander’s diplomacy was not without failures. His effort to integrate Persians into his administration alienated many of his Macedonian troops. The Opis Mutiny of 324 BCE exposed deep fractures – over identity, loyalty, and the limits of cultural synthesis.

Perhaps most personally damaging was his killing of Cleitus the Black, a senior officer and trusted companion, during a heated argument. It was more than a tragic misstep – it was a breakdown in internal diplomacy: a failure to manage dissent, emotion, and competing traditions within his own ranks.

Most critically, Alexander died without naming a successor. His empire fragmented almost immediately into rival Hellenistic kingdoms. This was not just a failure of statecraft – it was a failure of leadership. Durable governance requires foresight, continuity, and the institutions or mechanisms to sustain it. Alexander left none.

Yet Alexander’s legacy persisted. The Hellenistic world – a fusion of Greek, Egyptian, Persian, and Central Asian elements – endured for centuries. His methods of inclusion, symbolic legitimacy, and negotiated authority helped shape new political cultures long after his empire collapsed.

In parts of the Middle East, when the desert wind stirs the sand and whispers past ruined stones some still say: Iskander passes.

The man is long gone. But the legacy lives – not just in monuments, but in memory. In influence. In diplomacy without borders.

Alexander understood perception. He commissioned official histories, projected divine status, and issued coinage bearing his image. This was ancient information diplomacy. And it was also propaganda. Image, narrative, and memory were all part of his political toolkit. He was not only a master of war, but a master of spin, narrative control, and perception management – crafting the message as carefully as he planned his campaigns.

The enduring diplomatic lens

Alexander’s leadership was not merely tactical. It was strategic. He balanced force with accommodation, and centralised ambition with localized legitimacy. He was no democrat. But he understood that sustainable power required more than conquest. It required reconciliation.

In today’s diplomacy, we grapple with many of the same fundamentals: managing difference, shaping perception, sustaining legitimacy, controlling information, countering propaganda, and planning for continuity. Alexander’s world was different in form – but not always in substance.

He was flawed, often ruthless, and consumed by ambition. But he was also pragmatic, adaptable, and attuned to power dynamics beyond the battlefield. If diplomacy is the management of relationships across differences and interests, then Alexander practised a form of it.

Statesmanship, statecraft, and strategy were all present in his rule, though not institutionalised as we know them today. Yet what endures is not brute domination, but the capacity to harmonise difference: to reconcile rival interests, to bridge cultural divides, and to temper ambition with understanding.

Alexander understood that conquest alone does not forge lasting legacy. It is tolerance, adaptation, and strategic integration that stand the test of time.

In diplomacy, as in history, the measure of greatness is not what is seized – but what is brought together and made to endure.

Euripides L. Evriviades, ambassador (Ad Hon.) and senior fellow, Cyprus Centre for European and International Affairs, University of Nicosia.

Click here to change your cookie preferences