By Marios Papageorgiou

Every year on World Fisheries Day, communities around the globe reflect on the immense importance of fisheries to our food systems, livelihoods, coastal cultures, economies and marine ecosystems.

From small island villages to bustling Mediterranean ports including our own communities in Cyprus and the wider region, fisheries have fed people for millennia and remain essential to the livelihoods of millions today.

Yet this year’s reflection carries particular weight: the world’s fisheries are under unprecedented pressure, while also showing signs of resilience where sustainable management has begun to take hold.

This article offers an overview of the state of global and Mediterranean fisheries, their value to society, the threats they face and why the future of sustainable oceans depends on empowering small-scale, low-impact fishing communities.

The global status of fisheries

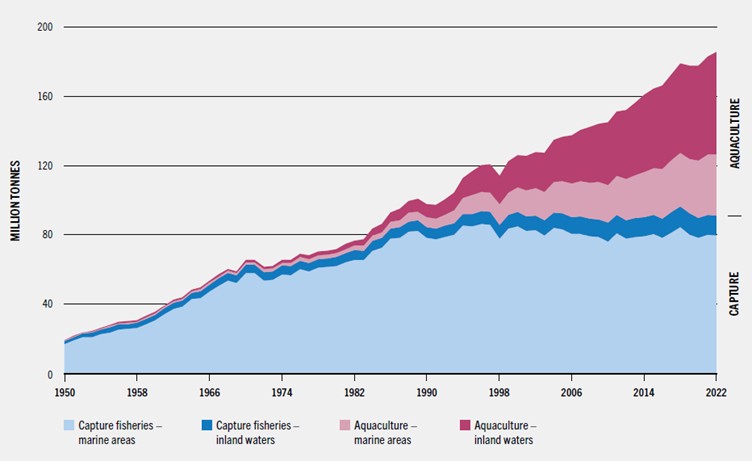

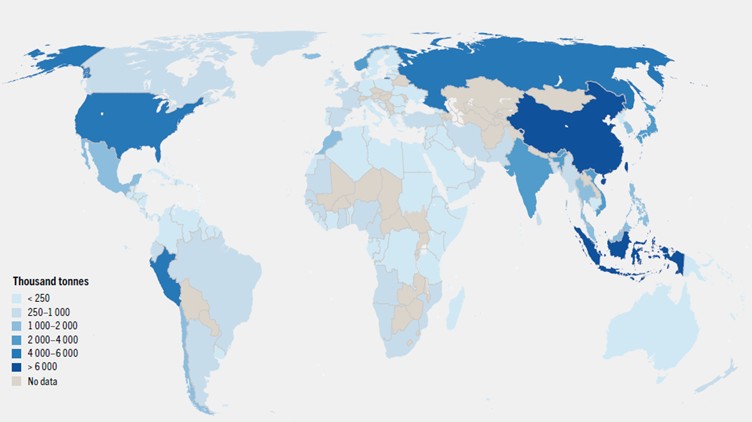

According to the latest FAO State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024, global aquatic food production reached 185.4 million tonnes in 2022, of which 164.6 million tonnes were aquatic animals destined for direct human consumption (the remainder being algae).

Aquaculture continues to expand and for the first time surpassed wild-capture fisheries in total volume (94.4 million tonnes), while global capture fisheries remain relatively stable around 91 million tonnes.

Aquatic foods have never been more important for nutrition, contributing vital protein, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins and minerals. For many coastal and island communities, fish is the most affordable and accessible source of animal protein.

Yet sustainability challenges persist. Globally, only 62.3 per cent of assessed fish stocks are fished within biologically sustainable levels, meaning that 37.7 per cent are overfished, a continued long-term decline.

This trend reflects growing fishing pressure, climate-related shifts and inadequate management in many regions. Many stocks, particularly in tropical regions and semi-enclosed seas, remain overexploited.

Why fisheries matter to food security, economies and communities

Fisheries are not only about food, they are about people, culture and place. Globally:

- Over 60 million people work directly in fisheries and aquaculture.

- Tens of millions more depend on related industries such as processing, logistics and trade.

- Fish is one of the most traded food commodities worldwide, contributing significantly to foreign exchange earnings.

For coastal communities, fishing is often the backbone of local economies and a cornerstone of cultural identity. It provides livelihoods and sustains traditions that have shaped societies for centuries.

Threats Facing the Fisheries Sector and the Marine Environment

Fisheries today cause and face a combination of several environmental issues. These threats interact and amplify each other.

1. Overfishing and stock depletion

Many fish stocks worldwide remain fully exploited or overexploited. While good management has led to recovery in certain regions, overfishing continues to threaten future productivity. In some areas such as the Eastern Mediterranean and parts of the Southeast Pacific, less than half of assessed stocks are fished sustainably.

2. Habitat destruction, particularly from industrial fishing

Destructive gears such as bottom trawls and dredges can damage seafloor habitats, including seagrass beds, corals, sponges and deep-sea ecosystems. These habitats are nursery grounds for many species and critical for biodiversity and coastal protection. Deep-sea habitats are particularly vulnerable because they are dominated by slow-growing species and fragile benthic communities which can take decades or centuries to recover.

3. Bycatch and discards

Bycatch, the capture of non-target species, is one of the most persistent challenges in global fisheries. The FAO acknowledges that bycatch affects a wide range of species, including sharks, rays, sea turtles, seabirds, juvenile fish and non-commercial species.

A global synthesis of available data suggests that:

- About 40 million tonnes of marine life are caught as bycatch each year.

- This represents 35–40 per cent of global marine catches.

- Large amounts are discarded, often dead or dying, contributing substantial hidden mortality.

In the Mediterranean, discard rates remain high and data are often incomplete. FAO–GFCM reports highlight that discards include juvenile commercial species, vulnerable species such as elasmobranchs, turtles and marine mammals and non-indigenous species, making it difficult to accurately assess fishing pressure and stock status.

In some Mediterranean fisheries, bycatch can exceed the volume of the target species, especially in bottom-trawl and small-scale gillnet fisheries.

4. Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing

IUU fishing undermines legitimate fishers, weakens governance, and accelerates stock declines. It is especially problematic in regions with limited monitoring and enforcement capacity.

5. Climate change and non-native and invasive species

Climate change is transforming marine ecosystems. Rising temperatures, shifting currents, ocean acidification and extreme weather events alter species distribution, modify productivity, and change the timing of key biological processes.

FAO highlights that climate-related risks are worsened by “invasions by escapees and non-native species,” particularly where governance is limited.

In the Mediterranean, one of the fastest-warming seas in the world, hundreds of non-native species have already entered through the Suez Canal and other pathways. Some, such as rabbitfish, lionfish and pufferfish, are now established and have profound ecological and socio-economic impacts.

These invasions, driven in part by warming seas and altered environmental conditions create new pressures on native biodiversity and fisheries-dependent livelihoods.

The status of Mediterranean fisheries

The Mediterranean and Black Sea region remains one of the most heavily exploited marine basins in the world. Yet recent FAO–GFCM results show cautious optimism:

- Overfished stocks fell from 73 per cent in 2020 to 58 per cent in 2021 – the lowest in a decade.

- Regional fishing pressure has dropped 31 per cent since 2012 due to management measures.

- However, fishing pressure remains twice the sustainable level overall, and many demersal species remain overexploited.

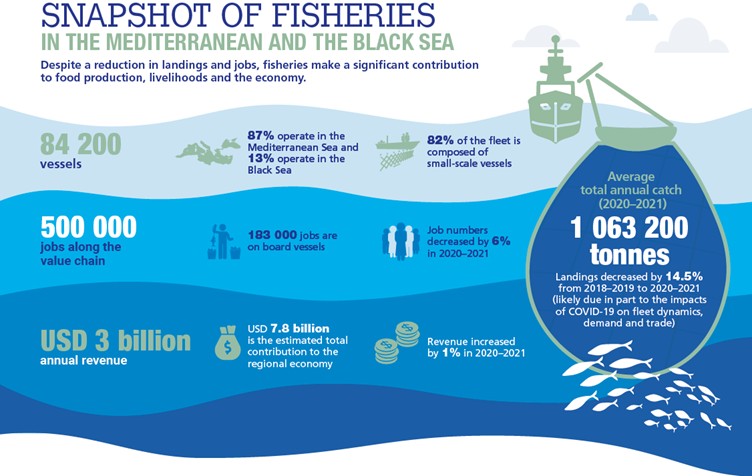

The region’s fisheries provide:

- Nearly 1.1 million tonnes of total annual capture fisheries.

- USD 3 billion in economic value.

- More than 500,000 jobs along the value chain.

Small-scale fisheries dominate the fleet (82 per cent of vessels) and employment (61 per cent), underscoring their socio-economic importance.

Amid these challenges, one segment stands out as essential for both environmental sustainability and community resilience.

The importance of small-scale and low-impact fisheries

Small-scale fisheries (SSF) are central to both human wellbeing and ecological sustainability. Compared to industrial operations, SSF generally use more selective, low-impact gears and have smaller carbon footprints.

They:

- Provide fresh, high-quality food to local communities.

- Preserve cultural heritage and traditional ecological knowledge.

- Support coastal economies with relatively low environmental damage.

- Play a critical role in stewardship of marine ecosystems.

Empowering SSF means providing fair access to resources, investing in infrastructure, supporting selective gear innovations, improving monitoring and data collection, and ensuring their voices are heard in policy-making.

A call for stewardship and sustainable transformation

This World Fisheries Day reminds us that the future of fisheries is inseparable from the future of our oceans and the coastal communities who depend on them. While global challenges are significant, from overfishing and bycatch to climate change and biological invasions, there is also clear evidence that effective management works.

Sustainable fisheries are possible. Rebuilding stocks is achievable. Protecting ecosystems is essential. And supporting small-scale, low-impact fisheries is not just a conservation priority but a social, cultural and economic necessity.

If we act decisively, we can ensure that fisheries continue to provide nutritious food, decent livelihoods and thriving marine ecosystems for generations to come. On this World Fisheries Day, we are reminded that protecting fisheries is not only a scientific or policy challenge but a shared responsibility that begins with informed citizens and empowered coastal communities.

Marios Papageorgiou is a marine biologist and executive director at Enalia Physis Environmental Research Centre.

The article was produced in collaboration with the Center for Social Innovation under the framework of the LEVERS project

Click here to change your cookie preferences