But in the UK it has been a long road to get there, and could only help Huw Edwards as far as his conscience allowed

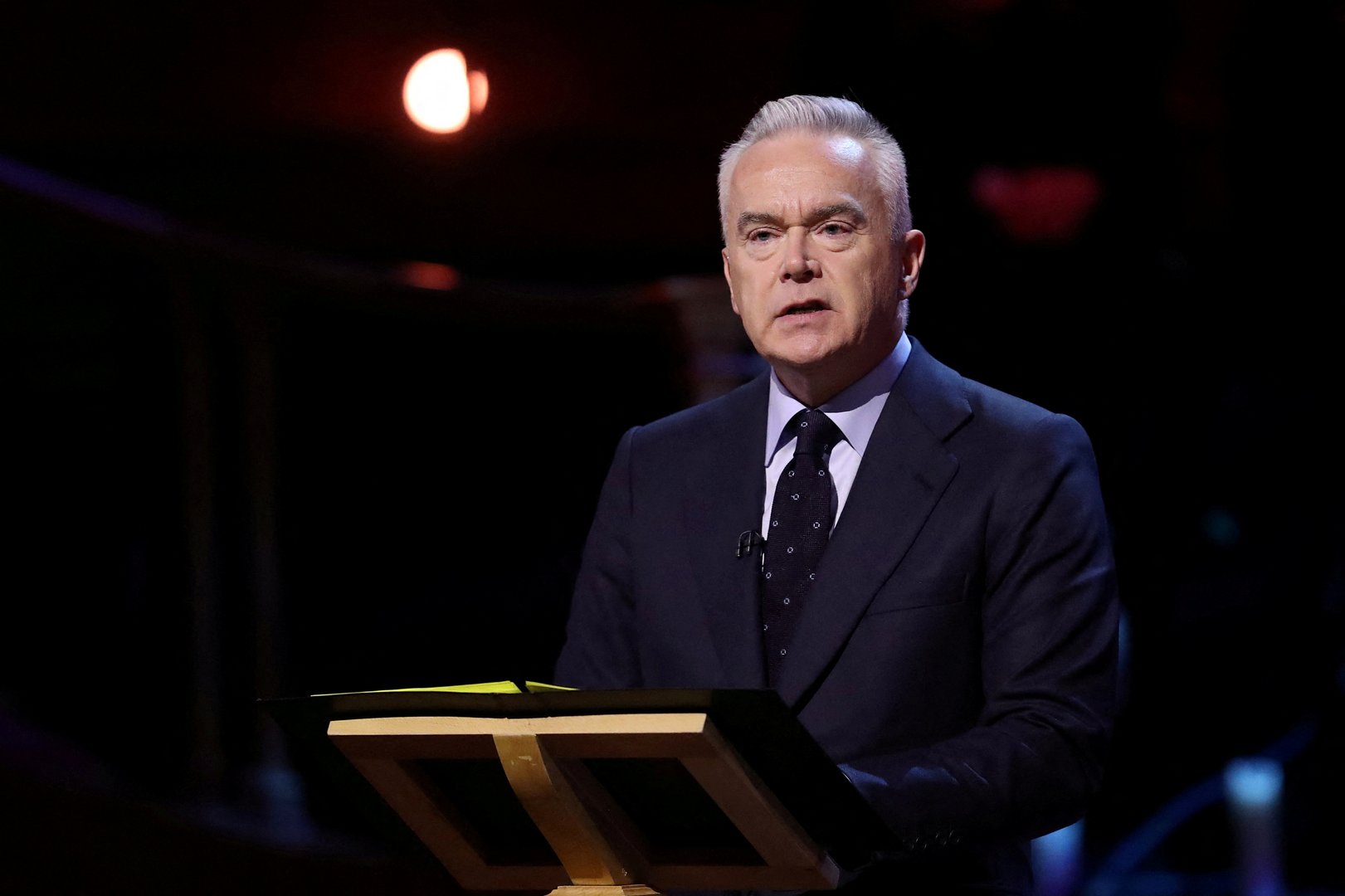

Huw Edwards was the unnamed mystery BBC presenter who exchanged sexually explicit pictures with a young man that caused such a furore in UK last week. He has been the highly respected public face of the BBC and of Britain on big occasions like the death and funeral of Queen Elizabeth II and the coronation of King Charles III.

His wife revealed he was the mystery presenter. She said he is unwell and receiving treatment for mental health issues, presumably exacerbated by the exposure of his indiscretion. The revelation came as a shock to most people in Britain, but after the initial shock there has been a flood of sympathy for Edwards and his family and for the young man at the centre of the story.

At a more mundane level Huw Edwards’ indiscretion was a much-ado-about-nothing story got up by the Sun newspaper – a sensationalist tabloid in Britain with a reputation for silly headlines – that failed to inform its readers that the young man made no complaint about Edwards – a serious editorial omission that gave the story an edge it did not possess.

What sustained the story for so long, however, was that neither the Sun nor any other media outlet was prepared to name Huw Edwards as the mystery presenter because they all respected his right to private life under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) enshrined in UK law since 1998.

In the end it was Huw Edwards’ wife who revealed his identity on his behalf – perhaps to lift public suspicion of other presenters. All media outlets were unwilling to invade his or the young man’s privacy by revealing their identity, which marks a turning point in an otherwise unruly media environment.

The way the law of privacy developed that enabled Huw Edwards’ identity to be kept secret is interesting and shows that the right to privacy is not just fundamental; to most people it is sacrosanct. The development of the law involved a transition from breach of confidence via the ECHR to a full-blown law of privacy developed by judges on the back of celebrities rich enough to engage in expensive litigation.

First off was the case the well-known supermodel Naomi Campbell brought against Mirror Group Newspapers in 2001. She boasted that unlike many other supermodels she did not take drugs. Unfortunately for her she was pictured by the Daily Mirror attending drugs rehab anonymous with an article about her and her drug addiction. She sued the newspaper for breach of private confidential information and obtained modest damages from Justice Moreland in the High Court, reversed by the Court of Appeal but upheld by the judicial committee of the House of Lords, now the Supreme Court.

Some of the judges ruled that where a prominent figure boasts an untruth, the press is entitled to set the record straight, but the majority thought that privacy is crucial for one’s drugs rehab and that the invasion of Naomi Campbell’s privacy could not be justified despite the weight given to freedom of expression of the press.

The importance of the case is that one of the judges coined the test for the right to protection of one’s private life under the ECHR as being: whether in respect of the facts disclosed the person affected has a reasonable expectation of privacy?

The court also gave guidance on how the competing right of freedom of expression was to be resolved, because in many cases the right to privacy clashes with the exercise of the right to freedom of expression. Basically, the two rights are equal, but the right to privacy trumps freedom of expression if its curtailment is necessary and proportionate for the protection of the reputation or rights of persons with a reasonable expectation of privacy.

Next up was the case of the pop singer Cliff Richard who sued the BBC for invasion of his privacy in the investigation of a historical sex offence. Cliff Richard has been a pop singer since his first song, Living Doll, in 1959. Other songs of his include the Young Ones in 1962, Summer Holiday in 1963 and Congratulations in 1968. All his songs are a bit schmaltzy, but Cliff Richard remained popular with a reputation for being a nice guy and a good Christian.

Until that is in 2014 when the police began to investigate a historical sex allegation against him at a Billy Graham evangelical gathering in the early 1980s, as part of a wide ranging operation that targeted a number of popular entertainers.

Someone close to the investigation gave the BBC advance notice of a police search of Cliff Richards’ Yorkshire home in connection with the allegation. Quite what the police were searching for some 30 years after the event is not clear, but the search went ahead and the BBC went completely over the top with its reporting of the search using a helicopter to film the search of his home – for dramatic effect no doubt but wholly disproportionate to the search.

In the event the investigation yielded nothing against the singer, and he was not charged with any offence. Presumably to kill the stigma that attaches when such investigations are publicised, Cliff Richard sued the BBC claiming damages for gross invasion of his privacy and in 2018 Justice Mann found the BBC liable and awarded him £220,000 compensation that included aggravated damages.

The case is important because it extended the protection of the right to private life to investigations of crime by the police for suspected criminal behaviour on the ground that suspects can have a reasonable expectation of privacy. Cases are fact-sensitive and it depends on all the circumstances. As the very public investigation of Scotland’s former First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, shows, she and her husband were very publicly investigated concerning the SNP’s finances presumably because given who they were in Scottish public life they did not have a reasonable expectation of privacy or if they had it could not trump freedom of expression.

Huw Edwards will probably not return to anchor BBC News at Ten again. In any case he needs the time and space to recover. On the evidence in the public domain so far, he has paid a heavy price for a relatively minor indiscretion but full marks to the press for respecting his privacy.

Alper Ali Riza is a king’s counsel in the UK and a retired part time judge

Click here to change your cookie preferences