Discovering the meaning of life and death

‘What would you write if you had to write your obituary? Today, right now.’

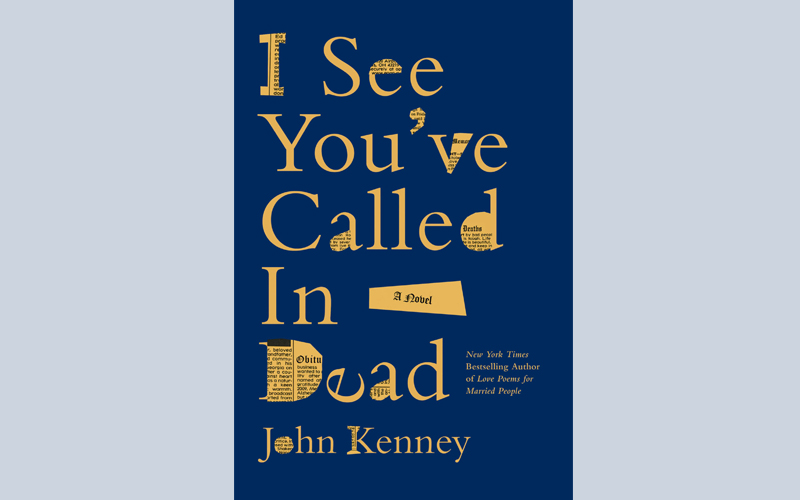

Avid readers of this column (I’ve always wanted to write this, but don’t worry; I’m not actually deluded enough to believe they – you? – exist) will know that I have a tendency to rail against the excessively bleak and self-pitying in literature, against those writers who seek to generate sympathy through mopiness or edginess through relentless negativity. Because what’s the point of art if not to elevate and uplift? If it doesn’t take the sadness and absurdity and pain and horror of being a human and make it into something beautiful? Anyway, that’s what John Kenney manages in his latest novel, and I am deeply grateful to him for doing so.

Death is everywhere in I See You’ve Called in Dead. Bud Stanley is a middle-aged obituary writer for an international news agency, and Bud’s life isn’t going too well. Divorced, single, both parents deceased, only brother on the other side of the world, a job that has ceased to mean anything to him, Bud decides to accept the offer of a blind date. When the woman shows up with her ex-now-current-boyfriend in tow, Bud loses it. So, naturally, he goes home, gets drunk and writes his own obituary – in which he was ‘a member of the Jamaican Bobsled Team, ninth in line to the British throne, and inventor of toothpaste’ – before publishing it on the company website for the world to read.

Suspended with pay but not yet ‘terminated’ because he is officially dead and therefore still in possession of some rights according to the HR software governing his, and apparently every other employee’s, future, Bud unwittingly sets off on a journey to discover the meaning of death, and with it the point of being alive. He does so by taking up a beautiful stranger’s invitation to start attending the wakes and funerals of strangers, along with his friend, landlord and emotional pillar, Tim Charvat, whose reflections on life as a paraplegic (or, in his words, ‘half-man’) play a vital role in the emergence of Bud’s eventual understanding.

You can see the comic premise in everything I’ve written above, and this is a very funny book. But it is also a book that touches tenderly and wisely upon the darkness and lunacy and uncertainty of life. Ultimately, it is left to an eight year old to teach Bud and the reader about what it means to really live: ‘When someone writes your obituary, you will like it because you will have laughed a lot during your life and you had friends and a dog and went to birthday parties with balloons and to the beach and so many things that at night, each night, when you go to bed, you will think, Wasn’t that a great day.’ Quoting that has pushed me past my word-limit for this review, but I don’t care, because I doubt that I will read a more moving or insightful sentence this year.

Click here to change your cookie preferences