The world of horse racing has come a long way since it had large crowds and race winners were treated like celebrities. THEO PANAYIDES meets a jockey with 400 first places under his belt who randomly fell into the sport far from his remote village home

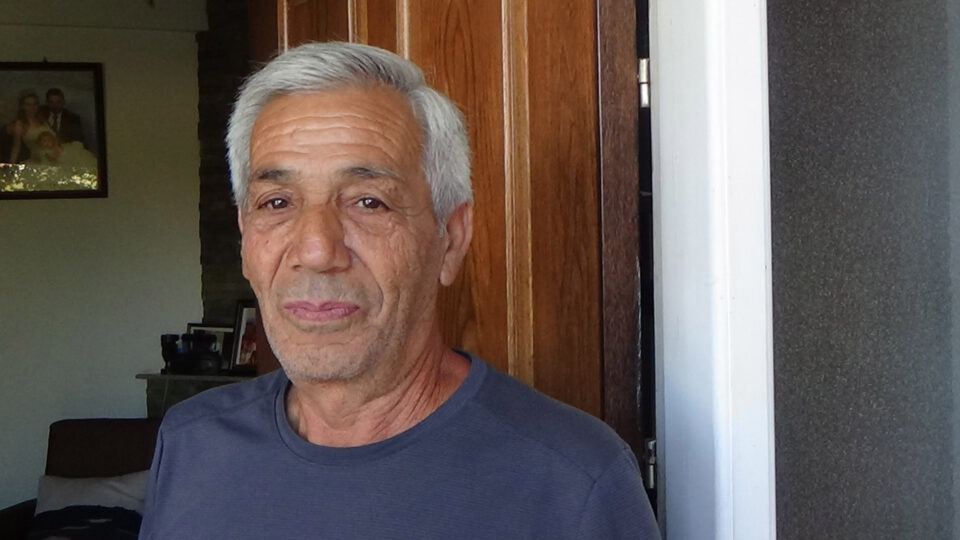

Alkiviades Nicolaou is a little shy at first – or not shy but silent, scoping me out. He sits watching daytime TV with the sound turned down in his house in Lakatamia, while I busy myself with my notebook and his wife Astero brings a glass of water (I’ve declined the offer of coffee) and a plate of biscuits. “Where are you from?” he asks at last – the classic salvo of an older generation, from a time when Nicosia was swollen with an influx from the villages. It’s always seemed a slightly quaint question, on such a small island – though he himself is village-born, from Pomos up the coast from Polis, which is remote even now and almost unknown when he first arrived. “’Pomos? Where’s that?’” people would say. “They learned about it later,” he adds with grim satisfaction – ‘later’ meaning when he became successful, and indeed quite famous.

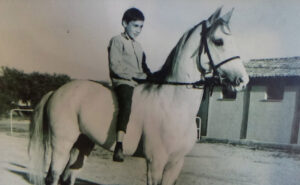

He arrived in 1967, at the age of 12, to become a jockey at the Nicosia racecourse. Why him? He had an uncle, he replies, who used to train horses and brought him down from the village. Yes – but why him specifically? His older brothers were too old, he shrugs (there were eight kids in total), the younger ones too young. It was all quite fortuitous. So he wasn’t particularly good with horses? “Where would we find a horse in Pomos? I didn’t know a thing about horses.”

His dad was initially against the move; Alkiviades had just passed the high-school exam, and might’ve continued his education. “I said to him, ‘What if I finish high school, what then? Are you going to send me to university?’. He swung his hand, and gave me a hell of a slap!” He laughs at the recollection, a compact, deliberate man with a tanned, weathered face. The house is full of photos, many of Astero and their three daughters and four grandchildren but also many photos of horses – horses with names he still recalls, like those of old friends. Satrapis, the first horse he ever raced, as a boy of 14. Freeway, whom the owner gave to Alkiviades to ride even though his (the owner’s) brother was also a jockey. Mannix, presumably named after the 70s cop show – though Mannix isn’t actually in the photos, being a temperamental horse who wouldn’t even come out of the gate unless Alkiviades was the rider. Why? “I don’t know.” It’s not like they were especially close, in fact he barely knew the animal – yet it wouldn’t race, except with him. Horses for courses, I suppose.

His dad was initially against the move; Alkiviades had just passed the high-school exam, and might’ve continued his education. “I said to him, ‘What if I finish high school, what then? Are you going to send me to university?’. He swung his hand, and gave me a hell of a slap!” He laughs at the recollection, a compact, deliberate man with a tanned, weathered face. The house is full of photos, many of Astero and their three daughters and four grandchildren but also many photos of horses – horses with names he still recalls, like those of old friends. Satrapis, the first horse he ever raced, as a boy of 14. Freeway, whom the owner gave to Alkiviades to ride even though his (the owner’s) brother was also a jockey. Mannix, presumably named after the 70s cop show – though Mannix isn’t actually in the photos, being a temperamental horse who wouldn’t even come out of the gate unless Alkiviades was the rider. Why? “I don’t know.” It’s not like they were especially close, in fact he barely knew the animal – yet it wouldn’t race, except with him. Horses for courses, I suppose.

The move to Nicosia turned out to be a stroke of luck. The boy, it transpired, was good with horses – and ended up racing them for about 20 years, till 1990, amassing some 400 first-place finishes. It’d surely be even more today, he muses: after all, they only raced on Sundays back then, and only six races at a time (he’d ride in two, maybe three), whereas now it’s twice a week, Wednesday and Sunday, and the number of horses in each race has doubled. A mediocre rider can make a living just from riding these days – they get €35 per race; Alkiviades used to get £2 – without even having to win. In every other way, however, being a jockey today is worse than it was in his day – and in fact our conversation is largely a tale of decline, delivered in his slow, equable way with chuckles of wry disbelief.

Back in his day, they did everything; the hours were brutal. He’d wake up at three, work in the stables till 11, then five or six more hours in the afternoon. (His canny uncle didn’t let him go back to Pomos for five years, fearing he wouldn’t return if he got a taste of freedom.) The jockeys doubled as unpaid labour, cleaning the animals, drying them off – but they also bonded with the horses, and took care of them properly. These days, he says disapprovingly, the jockey goes home after training and an assistant takes over “and, with the horse all sweaty, grabs a hose and hoses him down… No wonder you don’t find good horses anymore”. You can’t just rinse a horse and stick him in a stall, he’ll strain a muscle; you have to walk him up and down for at least 20 minutes, wiping the sweat off gently.

The whole sport has changed, from the ground up. There were no betting shops and bookies’ offices in his day, there was only the racecourse; it was packed every Sunday, 7-8,000 people from all over Cyprus. “Once there were two horses running together – both really good horses – and the crowd were split like it was Omonia-Apoel. Half the stand cheering for this one, half for that one.” People weren’t so cynical, he says, maybe with a touch of nostalgia (he actually stayed on as a trainer till about 2009, so he witnessed the decline at first hand); the sport was clean – despite what disgruntled punters said when a horse underperformed – nor did anyone ever try to bribe him to throw a race. Above all, there was camaraderie. “We’d finish work, but we wouldn’t leave – we’d sit at the canteen, we didn’t want to leave… These days, if you go to the canteen of the Race Club even at 10 or 11am, you won’t see a soul there. Nobody stays.”

The whole sport has changed, from the ground up. There were no betting shops and bookies’ offices in his day, there was only the racecourse; it was packed every Sunday, 7-8,000 people from all over Cyprus. “Once there were two horses running together – both really good horses – and the crowd were split like it was Omonia-Apoel. Half the stand cheering for this one, half for that one.” People weren’t so cynical, he says, maybe with a touch of nostalgia (he actually stayed on as a trainer till about 2009, so he witnessed the decline at first hand); the sport was clean – despite what disgruntled punters said when a horse underperformed – nor did anyone ever try to bribe him to throw a race. Above all, there was camaraderie. “We’d finish work, but we wouldn’t leave – we’d sit at the canteen, we didn’t want to leave… These days, if you go to the canteen of the Race Club even at 10 or 11am, you won’t see a soul there. Nobody stays.”

Everyone tends to wear rose-coloured glasses when recalling their youth, of course – yet it does seem like being a jockey carried more prestige then than it does now. He was a celebrity, for one thing. “There was nothing else [at the time],” repeats Alkiviades. “Just football and horses”. When he went out (I assume to selected places, but still), food and drinks were always on the house; Astero recalls being startled by how many people stopped to greet her husband, when they first started going out. (‘Who was that?’ she’d ask; ‘No idea,’ he’d reply.) His relationship with the horse owners was also interesting – and the owners were proper rich businessmen, not like now (he says) when three or four small-timers might band together to buy a horse, hoping to make a quick buck. “You have to be financially independent, so you can say ‘I’m splashing out this money, 20-30,000 a year. If it works out, fine’. Most of the people now try to do it as a business, and end up getting ruined. It’s a hobby. It’s an expensive hobby.”

The owners were rich, indeed Alkiviades and his colleagues counted on it. They only made £2 per race, as already mentioned, so their main source of income was the six per cent share of any prize money and (especially) the generosity of owners. He recalls one gentleman from Kyrenia who told him to go to the car – Alkiviades had just won a race for him – where he’d find an envelope, “take it, it’s yours”. The envelope was thick, and our hero wondered if the man had made a mistake: “‘I don’t keep the horse to win money, I do it for sport. Today I’m happy so take it, it’s a gift,’ he says to me. £500! Before the invasion!”.

Yet the owners didn’t treat the jockeys as hired help, quite the opposite. “Almost every night I’d be with them, eating and drinking,” he replies (a bit surprisingly) when I ask if he ever saw them outside the racetrack. “Especially with Polyviou, Dr. Hadjicostas, Andreas Pepsi.” Mr. Polyviou owned a meat factory (he also owned Achilles II, a famous horse who ended up being sold to the Sultan of Oman, leading to Alkiviades spending several months in that country to smooth the horse’s passage); Andreas Pepsi was, I assume, the local franchise owner for Pepsi. Alkiviades wasn’t intimidated, allowing himself to be courted – one memorable night, Dr. Hadjicostas and a Greek shipowner took him “to a place in Aglandjia to eat steak,” both of them hoping to convince him to ride their horses – and speaking to the men on level terms. “You and I are through,” he told the Greek shipowner later, when they fell out over something.

What did they talk about, though, when they went out – a jockey from Pomos with a primary-school education and a doctor, or a factory owner? “Horses,” he replies, as if the answer were obvious. “They never asked about anything else.” It’s quite telling that he never used his connections to get business tips, or start a business of his own. I ask if there’s any other profession that might’ve tempted him – if he hadn’t, after all, fallen quite randomly into this profession – but he shakes his head; he’s happy with horses. (He’s doing some construction work these days, together with his brother and a cousin, but mostly just to keep busy.) I ask about hobbies or other interests, but again draw a blank. Nothing but horses.

Yet it’s not really horses per se, I suspect; it’s the craft. He was never cruel to a horse, but he’s not sentimental about them either; he talks about them in the way a carpenter might talk about crafting a table, talking of details and tricks of the trade. Always sit with your weight leaning forward. Never show fear. Let the horse have its way while it’s still in the gate, just before a race, don’t try to impose yourself then. Above all, be patient – and he is naturally patient, like any craftsman, unexcitable, a steadying influence. “He never yelled at [the girls],” laughs Astero when I ask what he was like as a dad. He was always being hired to break a rebellious or wild horse – but ‘break’ isn’t really the word, because you can’t do it with violence or fear, only with patience. The job is actually to calm a horse – and he’s always been calm, even in wartime, during the invasion.

That’s a little story in itself. He was just the right (i.e. wrong) age, staying in the army for 38 months and fighting on the front lines – though as a medic, and only briefly. He and his ambulance crew were ordered to Kyrenia (“Don’t go,” warned a mainland-Greek officer unexpectedly while they were still in camp; “You’ll be killed. The whole thing’s a set-up”). Also in the crew was Andros Miamiliotis, a popular footballer who played for Apoel and the national team; it’s an odd coincidence that two celebrity sportsmen were both in the same ambulance. Just before Kyrenia, planes appeared and strafed an artillery position just in front of them. They fled on foot and ducked under a bridge, and Miamiliotis started shaking badly, shouting that they were all going to die. “I said to him, ‘Wait till they kill us first, you’re going to die of fear at this rate’.”

How could he be so calm?

“What was I supposed to do,” he shrugs, “start crying?” Then again, there’s also a postscript – because the ambulance did eventually return to Nicosia and was immediately ordered back to the front, at which point Alkiviades simply dug in his heels and refused to go, even under threat of court-martial. His down-to-earth nature isn’t quite the same as being passive or compliant. You have to be firm, after all – and fearless – to deal with horses.

The horses sensed his nature; Freeway and Satrapis, Mannix and Apache and Achilles II and the rest of them – sensed his lack of fear but also responded to his patience and essentially gentle character. He never put on airs, he assures me, despite his fame. He never tried to skip work on Monday because he’d won a race on Sunday. He never squandered money, or gave tips on horses.

Those were good times, a young kid like him (and he looked even younger, due to his jockey’s build; he only weighed 40 kilos when he went in the army) winning races and hobnobbing with captains of industry. And now? The good times are over, the racecourse a shadow of its former self, all the old excitement and camaraderie reduced to the seedy business of betting in bookies’ shops. His girls have moved back to Pomos (the older two are married there), and he and Astero are thinking of joining them soon. “It was a pure world,” sighs Alkiviades, thinking back to his fortuitous career. “It was a different world” – and shuffles through an album of photos, the four-legged friends of his youth.